They Grew Human Brain Cells in Rats for the First Time, Then Noticed Something Strange

The experiment, which involved transplanting human brain organoids into rat embryos, allowed the cells to connect with the animals’ nervous systems and blood supply. As the organoids matured, they responded to external stimuli and even drove specific behaviors, demonstrating a previously unseen level of integration between human and non-human brain tissue.

The breakthrough aims to overcome a persistent problem in brain research: the absence of realistic human models. Rodent and primate brains provide only partial insight into how the human brain works. Organoids, small clusters of human cells derived from stem cells, could bridge this gap by offering researchers a biologically relevant model to explore complex neurological disorders. These organoids self-organize into distinct regions and mimic key brain functions, but early versions struggled to survive without blood flow or sensory input.

Rat Brains Respond to Human Cell Signals

The team of scientists implanted human brain organoids into developing rat embryos, watching as the cells formed millions of connections over time. Once embedded in the rat brain, the organoids began to receive oxygen and nutrients via the animal’s blood system, allowing them to develop specialized cell types and form functioning neural circuits.

In a key test of functionality, researchers stimulated a rat’s whiskers and observed that the implanted human neurons lit up in response, indicating sensory integration. Later, when the same human cells were activated with a laser, the rat walked over and took a drink of water, a behavior directly influenced by the transplanted tissue. This marked the first time that brain organoids not only survived in a foreign brain but controlled behavior, as reported by Popular Mechanics.

These results follow years of incremental progress. Several years ago, scientists first managed to implant human organoids into rodents. But the 2022 experiment marked the first time those implants visibly affected the host’s actions, crossing into new territory for synthetic-human integration.

Modeling Brain Disease with Living Tissue

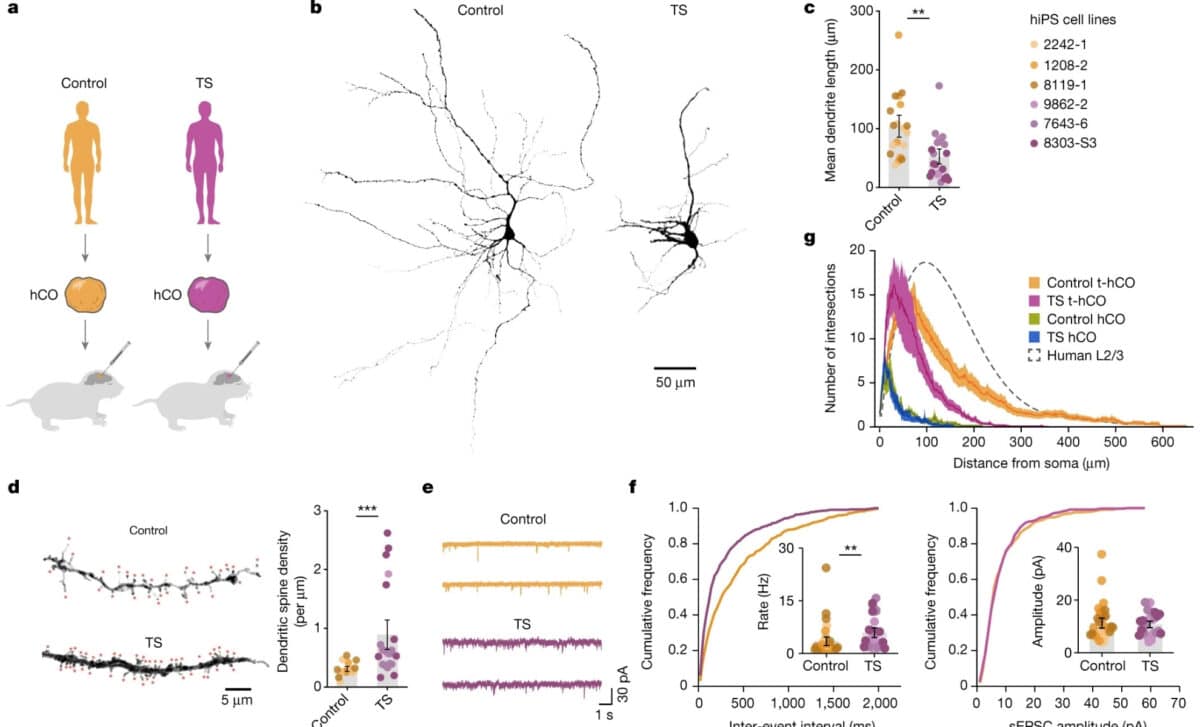

Organoids aren’t just a curiosity, they’re a window into human disease. Scientists have begun using them to simulate genetic disorders, growing organoids from patients with rare conditions to observe how brain cells behave differently in each case. For example, organoids made from individuals with Timothy syndrome showed specific neural abnormalities, while others created to study Rett’s syndrome revealed firing patterns similar to seizures.

These patient-specific organoids open the door to precision medicine, much like targeted cancer treatments today. According to neuroscientist Rusty Gage from the Salk Institute, future research may use organoids to test different therapies on a patient’s own brain cells before attempting treatment.

Even more surprising were findings in a separate study in 2019, where scientists attached electrodes to brain organoids and detected spontaneous electrical waves resembling human brain activity, including alpha, gamma, and delta frequencies. The cells even exhibited communication between different regions, something once thought impossible in such small-scale models. These advances were attributed to a new nutrient protocol that improved the longevity and complexity of the tissues.

Ethical Lines and Uncertain Boundaries

The possibility of creating increasingly complex brain models comes with growing ethical concerns. According to Karen Rommelfanger, who directs the neuroethics program at Emory University, the brain holds a unique status, not just biologically but culturally, as the seat of consciousness and identity. She points out that no one is disturbed by human kidney cells being implanted in a mouse, but the brain is different: “The brain controls our free will, how we make decisions, and how we perceive the world.”

Some scientists worry that as organoids grow more advanced, they might approach consciousness, even if there’s no way to empirically prove it. In fact, there’s still no clear medical consensus on whether a comatose human has consciousness, making it even more difficult to assess awareness in a lab-grown cluster of neurons.

To preempt ethical oversteps, the National Academies have advised researchers to closely monitor animal behavior for any signs of pain or unusual activity. The same report also recommends updating informed consent protocols for tissue donors, who may not be aware that their cells could end up in another species’ brain. According to legal expert Hank Greely of Stanford University, some donors change their minds once they learn about such uses, and failing to inform them risks undermining public trust in science.

The scientific community seems to agree that continued transparency and oversight are necessary. “What is driving this is not the urge to become Dr. Frankenstein,” Greely said. “It is to relieve human suffering.”

First Appeared on

Source link