The Brain Has a ‘Drainage Tunnel’ You Never Knew Existed, Now They’ve Found It

The discovery, made through dynamic MRI imaging and postmortem tissue analysis, reveals a slow-moving fluid flow in the dura mater consistent with lymphatic drainage. Researchers say this could redefine how we understand brain waste clearance and immune system interaction.

Brain drainage has remained a mystery for decades. The brain lacks traditional lymph nodes, yet it must remove waste products from cerebrospinal and interstitial fluids. Recent work has challenged the idea of the brain as an immune-isolated organ, and this new evidence adds to a growing body of research showing that meningeal lymphatic vessels might play a crucial role in keeping the brain clean.

The research, published in iScience and led by Onder Albayram, Ph.D., from the Medical University of South Carolina, builds on previous imaging breakthroughs, including those developed through a collaboration with NASA. The study’s focus was on healthy human subjects, and the team tracked fluid movement along the middle meningeal artery, a region until now not associated with fluid clearance.

Imaging Reveals Delayed Clearance Pattern in the Dura

In the study, five healthy adult participants underwent contrast-enhanced MRI scans over a six-hour period. Researchers observed that cerebrospinal fluid moved along the periphery of the middle meningeal artery (MMA) in a delayed and sustained manner. Signal enhancement peaked at 90 minutes post-injection, substantially later than what is seen in blood vessels, which typically show rapid uptake and washout.

This timing pattern, along with the absence of pulsatile flow, pointed to a lymphatic rather than vascular behavior. “We saw a flow pattern that didn’t behave like blood moving through an artery,” said Albayram, adding that the motion was “slower, more like drainage.” According to the researchers, the signal pattern around the MMA matched that of other regions previously implicated in meningeal lymphatic outflow, like the parasagittal dura.

To reinforce these findings, the team compared signal intensities across five anatomical regions. The peripheral MMA compartment showed delayed enhancement consistent with lymphatic-associated drainage and distinct from intravascular or mucosal behavior. According to the study, these patterns were observed consistently across participants and confirmed by double-blinded neuroradiologists.

Advanced Microscopy Confirms Presence of Lymphatic Structures

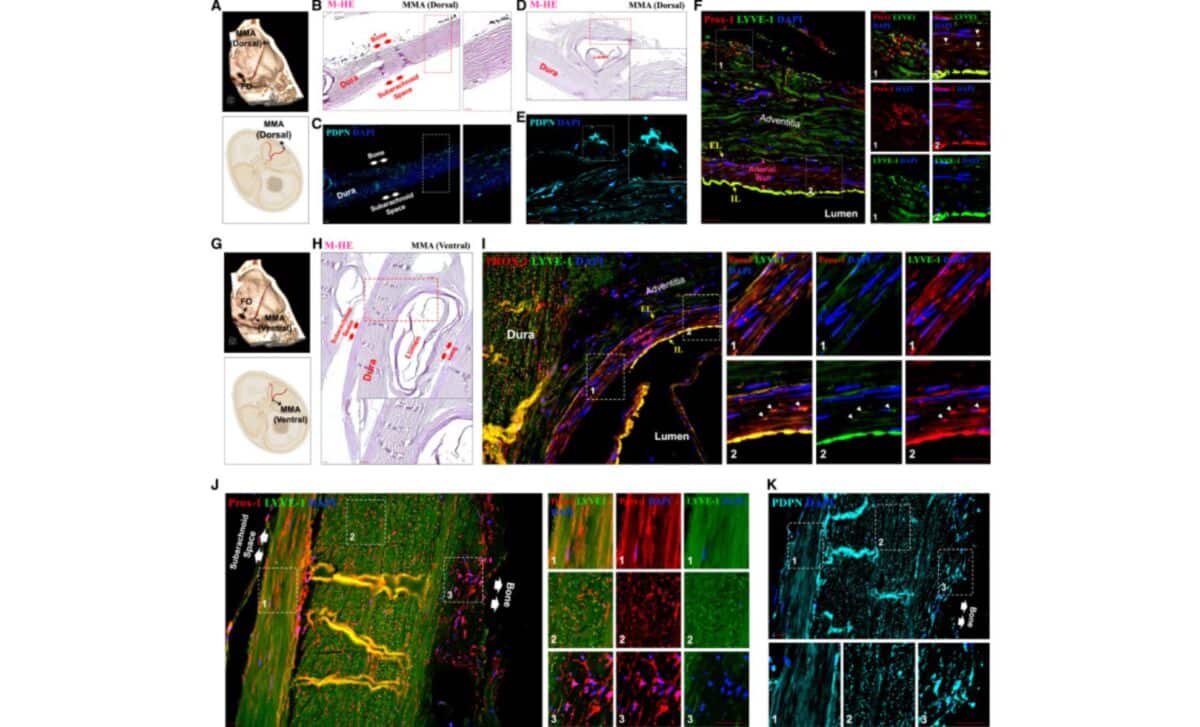

To validate the MRI findings, high-resolution imaging was performed on human brain tissue. The team dissected the dura surrounding both the dorsal and ventral portions of the MMA and applied confocal immunofluorescence and imaging mass cytometry (IMC) techniques. These methods revealed the presence of cells expressing PROX1, PDPN, and LYVE1, three markers typically associated with lymphatic endothelial identity.

According to the study published in iScience, these lymphatic-like structures were distributed in layered orientations across the dura. In the ventral dura near the foramen spinosum, vessels ran in anterior–posterior and superior–inferior patterns, forming a rich network. This layered configuration may suggest regional differences in drainage or communication with extracranial tissues.

Interestingly, while no lymphatic signal was detected within the arterial wall of the MMA itself, researchers observed scattered lymphatic marker-positive cells in the tunica media of the artery. Though the function of these cells remains undefined, their presence adds a new anatomical layer to what’s known about dural lymphatic organization.

Implications for Understanding Healthy and Diseased Brains

The study was conducted exclusively in healthy participants, which the researchers emphasized as a strength. “A major challenge in brain research is that we still don’t fully understand how a healthy brain functions and ages,” said Albayram. By establishing a baseline, future studies may better detect pathological deviations.

According to the authors, this ventral drainage pathway (if confirmed functionally) could play a role in neurological disorders where fluid clearance is impaired, such as Alzheimer’s disease or after traumatic brain injury. Although the study stops short of confirming a direct link, the researchers noted that they are already investigating drainage dynamics in patients with neurodegenerative diseases.

These findings challenge the long-held assumption that the meninges act as an impermeable barrier between the brain and the immune system. Instead, the evidence now supports a view of the dura as an active interface, one that hosts a complex and possibly compartmentalized lymphatic architecture capable of draining cerebrospinal and interstitial fluids toward peripheral clearance zones.

While the authors acknowledge the limitations of their study, including a small sample size and reliance on postmortem tissue for validation, the convergence of in vivo imaging and molecular mapping offers a robust framework for future exploration. As the team writes in iScience, this work “adds a critical dimension to the anatomical map of human CNS lymphatic pathways.”

First Appeared on

Source link