Scientists Found a Way to Regrow Cartilage Without Using Stem Cells

Cartilage is the body’s most stubborn tissue. Once it wears away, it’s usually gone for good. This biological dead-end is the engine behind osteoarthritis, a grueling condition that stiffens joints, fuels chronic pain, and eventually forces millions of people into the operating room for total joint replacements.

Now, in a study published in Science, researchers report that they were able to coax aging and injured joints in mice to regrow healthy cartilage. They did this using an unconventional approach: by blocking a single enzyme tied to aging. The same approach also triggered early signs of regeneration in human cartilage taken from knee replacement surgeries.

The work suggests that cartilage loss, long considered irreversible, may one day be treatable at its source.

The Aging Enzyme

As we age, the smooth cartilage cushioning our bones thins out. Unlike your skin or blood, cartilage doesn’t have a built-in “refresh” mechanism.

The new study traces much of that decline to an enzyme called 15-PGDH. Levels of the enzyme rise with age in many tissues, earning it the nickname “gerozyme.”

When the researchers compared knee cartilage from young and old mice, they found that 15-PGDH roughly doubled with age. Levels also climbed after joint injuries resembling torn anterior cruciate ligaments, a common trigger for osteoarthritis in people.

That pattern caught the researchers’ attention because 15-PGDH breaks down molecules known to support tissue repair. In earlier studies, blocking the enzyme helped aging mice rebuild muscle and improve strength. The team wondered whether cartilage might respond in a similar way.

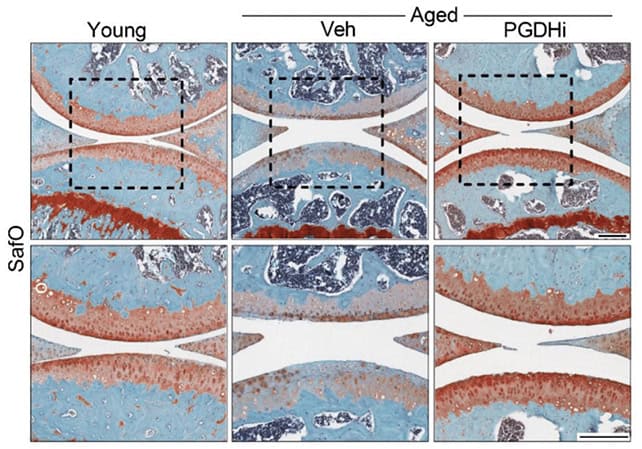

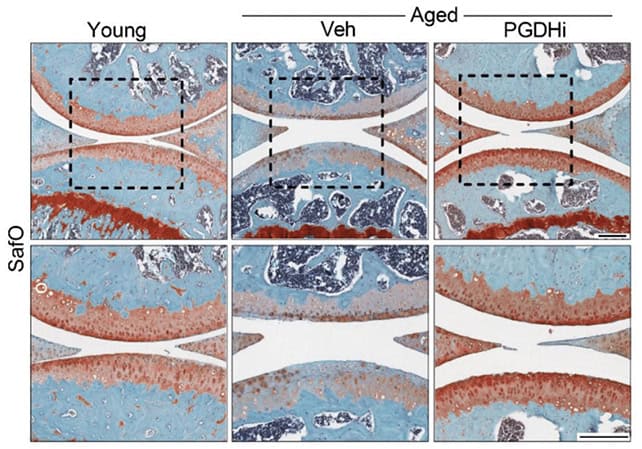

To test the idea, they treated older mice with a small-molecule drug that inhibits 15-PGDH. Some animals received the drug systemically; others got injections directly into the knee. In both cases, cartilage that had grown thin and ragged thickened across the joint surface.

Further analysis showed that the new tissue was hyaline cartilage—the glossy, low-friction type found in healthy joints—not the stiffer fibrocartilage that often forms during failed repair attempts.

“Cartilage regeneration to such an extent in aged mice took us by surprise,” said Nidhi Bhutani, an orthopaedic scientist and senior author of the study. “The effect was remarkable.”

Reprogramming, Not Replacing

The treatment also helped joints heal after injury. In mice with knee damage similar to a torn ACL (anterior cruciate ligament), researchers gave injections of the enzyme-blocking drug twice a week for a month. Those mice were far less likely to develop osteoarthritis than untreated animals, whose joints quickly deteriorated and showed high levels of the gerozyme.

The treated mice also walked more normally and put more weight on their injured legs. Their joints were showing signs of improvement and reduced discomfort—inferred from gait and weight-bearing on the affected limb.

What surprised the researchers most was how this recovery happened. For years, scientists have searched for stem cells in cartilage that might rebuild damaged joints. Those cells have remained elusive.

In this case, stem cells weren’t needed at all.

Rebuilding Cartilage

Instead, the researchers took a closer look at the cartilage cells already present in the joint. Using a technique that tracks gene activity in individual cells, they found that aging and injury push many cartilage cells into a harmful state. These cells produce 15-PGDH and other molecules that break down cartilage. At the same time, cells that normally help maintain healthy cartilage become less common.

Blocking 15-PGDH flipped that pattern. Cells involved in cartilage breakdown became rarer. Cells linked to the formation of stiff, inferior cartilage also declined. Meanwhile, the number of cells devoted to building and maintaining smooth, healthy joint cartilage nearly doubled.

The cartilage did not rebuild itself by making new cells. The existing cells changed their behavior.

“This is a new way of regenerating adult tissue, and it has significant clinical promise for treating arthritis due to aging or injury,” said Helen Blau, a stem cell biologist and senior author of the study. “We were looking for stem cells, but they are clearly not involved. It’s very exciting.”

Taken together, the findings suggest that cartilage retains an ability to repair itself long into adulthood. With age, that capacity appears to be switched off—but not permanently lost.

Early Signs in Human Tissue

Mouse studies often raise hopes that fade once switching to people. To test whether human cartilage might respond in the same way, the researchers turned to tissue removed during knee replacement surgeries.

They treated samples from patients with osteoarthritis with the 15-PGDH inhibitor for one week. The cartilage showed lower levels of the enzyme, reduced expression of genes tied to degradation and inflammation, and early signs of rebuilding the extracellular matrix that gives cartilage its function.

“The mechanism is quite striking and really shifted our perspective about how tissue regeneration can occur,” Bhutani said. “It’s clear that a large pool of already existing cells in cartilage are changing their gene expression patterns.”

The findings arrive amid a broader push to develop treatments that modify osteoarthritis itself, rather than simply easing pain. About one in five adults in the United States has the disease, which estimates costs of tens of billions of dollars a year in direct health care expenses. Current drugs do little to slow cartilage loss. When joints fail, surgery is often the only option.

By contrast, the enzyme-blocking approach aims at an upstream driver of degeneration. It also builds on existing work. An oral version of a 15-PGDH inhibitor is already in early clinical trials for age-related muscle weakness and has so far appeared safe in healthy volunteers.

That experience could accelerate efforts to test the drug in people with joint disease. Still, many questions remain. Mouse joints are not human joints, and regenerating cartilage in a living knee over years of use will be far more demanding than coaxing cells in a dish.

Even so, the study challenges a long-held assumption—that adult cartilage is beyond repair. Instead, it paints a picture of aging joints not as broken machines, but as systems stuck in the wrong setting.

First Appeared on

Source link