Scientists Uncover Thousands Of Mysterious Creatures Lurking Near A Deep-Sea Volcano

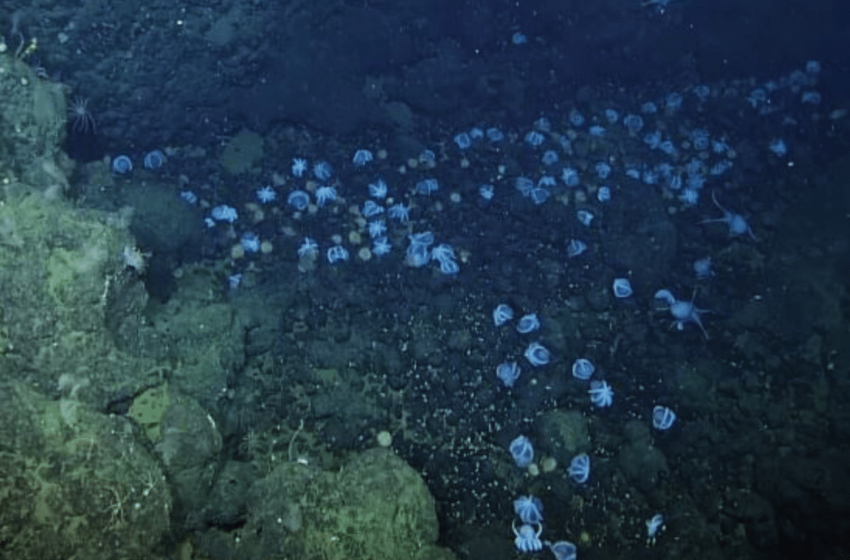

A vast aggregation of deep-sea octopuses has been documented nearly two miles beneath the surface off the coast of California, close to an underwater volcano. Observed and analyzed by the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute, this site, now known as the Octopus Garden, is the largest known gathering of octopuses on Earth and offers rare insight into how life adapts to the most hostile parts of the ocean.

A Discovery Hidden In The Darkness

The Octopus Garden lies on a rocky slope where the seafloor is fractured by subtle hydrothermal activity. In a region where temperatures usually hover just above freezing, researchers were surprised to find patches of unusually warm water emerging from cracks in the rock. These conditions have attracted thousands of Muusoctopus robustus, commonly called Pearl Octopuses, transforming an otherwise barren deep-sea landscape into a dense biological hub.

“Thanks to MBARI’s advanced marine technology and our partnership with other local researchers, we were able to observe the Octopus Garden in tremendous detail, which helped us discover why so many deep-sea octopus gather there. These findings can help us understand and protect other unique deep-sea habitats from climate impacts and other threats,” said Jim Barry, MBARI senior scientist and lead author of the study.

High-resolution imaging and long-term monitoring revealed more than 6,000 individual octopuses directly observed at the site, with population estimates reaching 20,000 animals. This density is extraordinary for a species typically considered solitary, especially under the intense pressure and darkness of the deep ocean.

(A) Map of Davidson Seamount and hydrothermal springs/octopus nursery sites. (1) Octopus Garden. (2) Octocone. Inset: Detail of the Octopus Garden hillock. Contour lines in meters. Central area mapped in high resolution (2.5 ha) indicated by central depth-color section. (B) Muusoctopus robustus females nesting in cracks influenced by hydrothermal springs. (C) Octopus with anthozoan anemones that benefit from the M. robustus carbon subsidy. (Science Advances)

Warmth, Survival, And Octopus Motherhood

In the deep sea, reproduction is a slow and risky process. Female octopuses brood their eggs for years, guarding them until they hatch, often without feeding. Cold temperatures dramatically slow embryo development, extending this vulnerable period. The Octopus Garden changes that equation.

“The deep sea is one of the most challenging environments on Earth, yet animals have evolved clever ways to cope with frigid temperatures, perpetual darkness, and extreme pressure. Very long brooding periods increase the likelihood that a mother’s eggs won’t survive. By nesting at hydrothermal springs, octopus moms give their offspring a leg up,” Barry explained.

Measurements taken at nesting sites showed temperatures approaching 11 degrees Celsius, far warmer than the surrounding deep ocean. This heat shortens incubation time, allowing eggs to hatch faster and reducing exposure to predators. For species where mothers die shortly after their eggs hatch, this thermal advantage directly influences reproductive success and population stability.

Clues Emerging From The Deep Ocean

The findings from the Octopus Garden were detailed in a peer-reviewed study published in Science Advances, adding weight to their broader ecological significance. The research highlights how even subtle geological features can create concentrated zones of life in the deep sea.

“Essential biological hotspots like this deep-sea nursery need to be protected,” Barry noted. “Climate change, fishing, and mining threaten the deep sea. Protecting the unique environments where deep-sea animals gather to feed or reproduce is critical, and MBARI’s research is providing the information that resource managers need for decision-making.”

By linking reproductive behavior directly to seafloor heat sources, the study reframes how scientists think about habitat selection in extreme environments. These insights extend beyond octopuses, offering clues about how other deep-sea species may respond to environmental change.

First Appeared on

Source link