How Modern and Antique Technologies Reveal a Dynamic Cosmos

Bradley Schaefer, an astronomer at Louisiana State University, focuses on cataclysmic variable stars, objects that vary in brightness over time due to some type of major turmoil. His favorites are recurrent novas — binary systems in which a massive white dwarf siphons so much material from its partner that its surface becomes dense enough and hot enough to undergo nuclear fusion, resulting in a dramatic increase in brightness at least twice per century. More common novas work in a similar way, but their white dwarfs are smaller, meaning their bursts are much less frequent.

Scientists think there could be a connection between recurrent novas and Type Ia supernovas. These supernovas are critically important for measuring the expansion rate of the universe. Schaefer is testing the theory that recurrent novas could evolve into Type Ia supernovas.

By measuring their brightness over years, potentially over multiple fusion bursts, Schaefer could observe patterns and changes in these orbital systems. He’s been able to track the orbital periods of more than a dozen systems, and he has ruled out a few of them as potential precursors to a special type of supernova explosion.

For this work, “you need many decades’ worth of data,” Schaefer said. “Archival data [is] the only game in town.”

Historical Outbursts

If and when something in the cosmos goes bang, astronomers want to know its history. Older data lets them observe earlier blips, flares, or other activity, and “that then helps the interpretation, and maybe suggests a different model,” Graham said.

The AGNs that Graham studies are active supermassive black holes and their surrounding accretion disks. These vary randomly, so describing their brightness changes is complex. While scientists have 60 years of targeted data and 5 million time series images of AGNs, he said, “we still really don’t understand the mechanisms by which they are variable.”

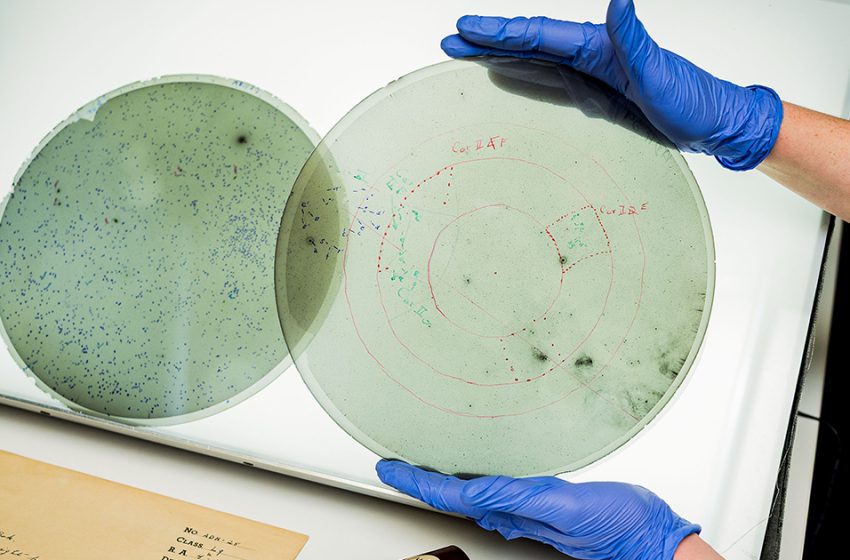

Graham is co-leader and project scientist at the Zwicky Transient Facility (ZTF), another sky survey looking for changing cosmic objects. ZTF uses the 48-inch Oschin Schmidt telescope at Mount Palomar in California. The telescope bridges the eras of observational astronomy. Today it boasts sophisticated digital detectors, but it was also used for foundational surveys in the days of glass photographic plates. Graham recently acquired 20 terabytes of historical data: the digitized versions of the plates captured during the Palomar Observatory Sky Survey (POSS), first conducted in the 1940s and 1950s, and its successor POSS-II, which spanned the 1980s and 1990s.

This won’t be the first time he has combined data from multiple surveys, although in the past he’s focused on putting together digital surveys only. Combining datasets from multiple telescopes and observations requires calibration to account for different optics, filters, and detectors.

A physical plate, or a scanned image of one, adds further complications, Griffin said. The photographic emulsion’s density — those dark marks — relates in a very specific way to the incoming starlight’s intensity.

But the astronomers who know how to read the plates can combine their measurements with ones from more recent surveys for a longer-term view. Schaefer uses data from multiple space telescopes, but they’re not suited to his purpose unless paired with ground-based datasets and the more historical forms of observation. “It’s just one point,” he said of the space telescope images, “where the story is told over the century.”

Race Against Time

Every telescope that astronomers used to document the sky during the century before 1980 used glass plate photography. The plates, if stored in stable conditions and not piled up with weight on top of them, can endure for centuries.

Unfortunately, some collections were misplaced when university departments switched buildings. Others have even been thrown into the garbage. Of the many that have survived, their condition can be a concern; some glass plates are cracked or little more than shards. In other cases, the emulsion is peeling due to humidity swings or growing mold from water exposure.

Both Hudec and Griffin are strong proponents of the value in these historical artifacts. Both have also seen collections destroyed and data saved.

Griffin spoke of an experience at a collection overseas. She reached into a box filled with plate envelopes to pull out a plate with the spectrum of the bright star Arcturus. “The emulsion fell off,” she said. “Only the glass came up.” All the plates in the box were the same. They had apparently been moved too quickly from high humidity to low humidity.

Surviving plate collections can be a constant source of discovery. And with careful scanning, the data they hold can be invaluable, full of hidden surprises from a century of astronomical flares, bursts, and more. The Rubin Observatory will lead to many incredible discoveries; its early images already have. But the lifetimes of cosmic objects are long, and understanding today’s data relies on yesterday’s, in the form of stacks and stacks of glorious glass. That’s why, Griffin said, “it’s so desperately important to keep them.”

First Appeared on

Source link