The 3-Body Problem Just Got an Upgrade—and You Can Thank Einstein

I’ve yet to meet a physicist that didn’t believe in the beauty of the general theory of relativity—Einstein’s description of gravity as the curvature of spacetime. After all, it’s consistently reinforced a myriad of breakthroughs, especially in astrophysics. So when some cosmic phenomenon confuses scientists, it feels right for them to count on general relativity to find some answers.

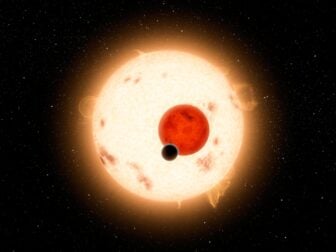

One such mystery, described in a recent paper in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, concerns circumbinary exoplanets—or rather, the shortage thereof—in the now 6,000+ exoplanets confirmed to date. Just like the planet Tatooine from the original Star Wars, circumbinary exoplanets orbit a pair of stars, as opposed to one.

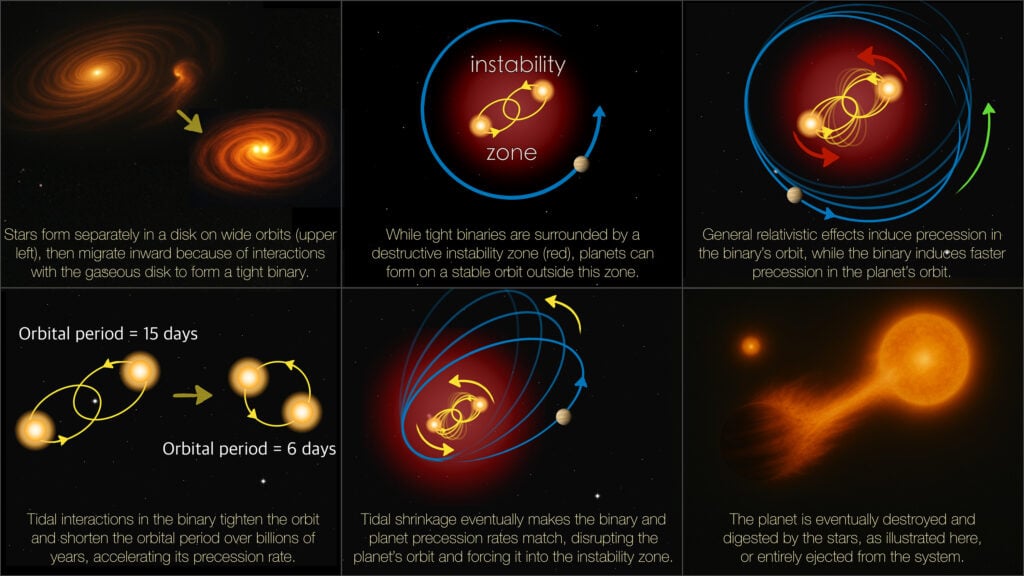

According to the new study, the scarcity of such planets around tight binaries (i.e., two stars in relative close proximity to each other) may in part be explained by the effects of general relativity on the three-body interactions between the two stars and the planet. The complex gravitational profile eventually results in the planet’s demise or orbital expulsion, according to the new research.

In search of double sunsets

That said, astronomers have assumed that binary stars shouldn’t be dramatically worse than solitary stars when it comes to forming large exoplanets; roughly 10% of solitary stars are known to host them. Holding on to those planets, however, may be a different story, as any that do form don’t always remain stable over the long term. The new research set out to ask why this is the case and which forces might be removing—or destabilizing—those planets over time.

During its run, Kepler spotted roughly 3,000 binary star systems. But of the 3,000, astronomers were only able to find 47 circumbinary planet candidates via the transit method, of which just 14 were actually confirmed to exist.

“You have a scarcity of circumbinary planets in general, and you have an absolute desert around binaries with orbital periods of seven days or less,” Mohammad Farhat, study lead author and a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement.

Flying too close to the stars

With his collaborator Jihad Touma, a physicist at the American University of Beirut in Lebanon, Farhat turned to Old Reliable: general relativity. The new research sought to discern whether the seeming scarcity of exoplanets around binary systems was the product of technological shortcomings or something else altogether, such as the impact of strong orbital effects that removed planet-like objects over time.

For the study, the researchers performed a mathematical analysis to assess the consequences of relativistic forces around binary systems. As expected, general relativity offered some intriguing answers. Specifically, the researchers studied how general relativity might affect the orbits of tight binary systems to gradually shift their orientation and reshape the long-term gravitational environment.

In binary systems, stars wobble closer together over tens of millions of years, and their orbital parameters gradually shift and shrink. When a planet—or even the inklings of a budding planetesimal—enters into the mix, its orbit elongates into a thin oval, making its closest and farthest distance from the star even more extreme.

“And on the route, it encounters that instability zone around binaries, where three-body effects kick into place and gravitationally clear out the zone,” Touma explained.

This could mean one of two things: either the planet flies too close to the stars and becomes shredded by the stars, or the planet flies too far and exits the system altogether, Farhat said. “In both cases, you get rid of the planet.”

Missing or unreal?

Then again, it could just be that our detection methods for exoplanets aren’t enough. But assuming undiscovered Tatooine lookalikes exist, the latest analysis gives some explanation for why they’ve been such a pain to find. Those 14 circumbinary exoplanets we know of? Truly lucky finds.

On a different note, Farhat and Touma are now wondering whether a similar approach could illuminate how relativistic effects influence other unexplained, extreme cosmic phenomena. For instance, perhaps the same principle could explain the behavior of stars around binary supermassive black holes or pulsars, they said.

First Appeared on

Source link