The Roman Empire Built High-Tech Baths and Sewers, but This Fort’s Drain Just Uncovered a Dirty and Deadly Secret

For decades, Vindolanda has offered historians a detailed view into daily life on the Roman Empire’s northern frontier. Now, new scientific findings from its sanitation system have uncovered a chronic threat that plagued the soldiers stationed there.

A research team from the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford identified intestinal parasites in waste sediments at the site. Despite the presence of aqueducts, latrines, and public baths, the garrison appears to have suffered repeated exposure to contaminated water and food sources.

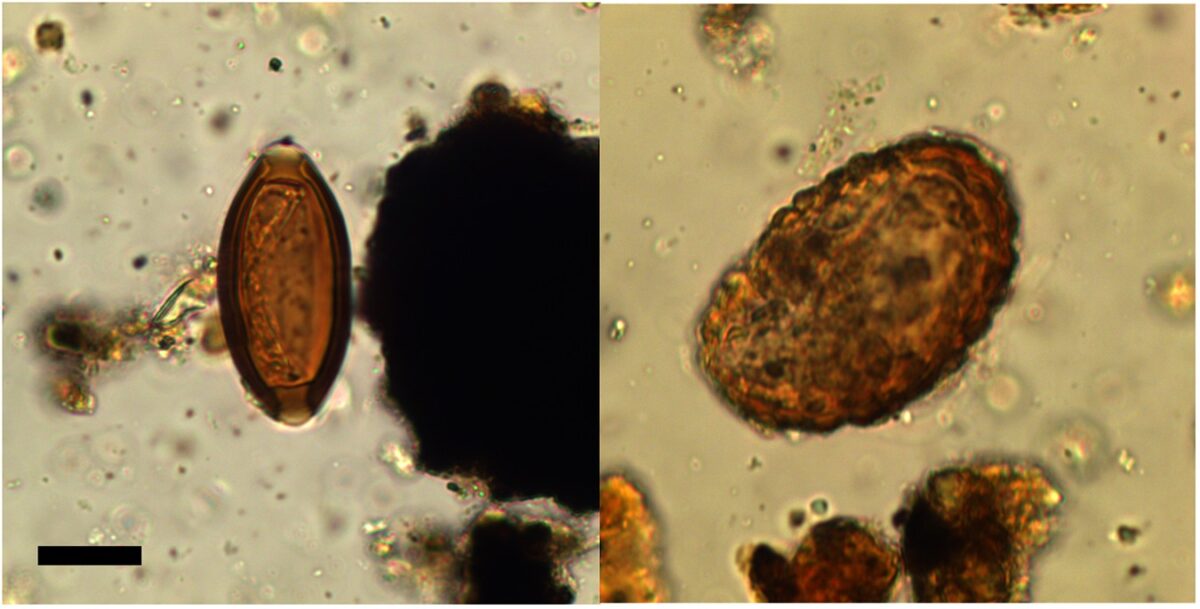

The study, published in the journal Parasitology, revealed microscopic traces of Giardia duodenalis in one of Vindolanda’s main drainage channels. This marks the first confirmed appearance of the protozoan parasite in Roman Britain. Helminth eggs from Ascaris and Trichuris were also identified, confirming long-term circulation of these pathogens at the site.

High-Tech Drains, Ancient Infections

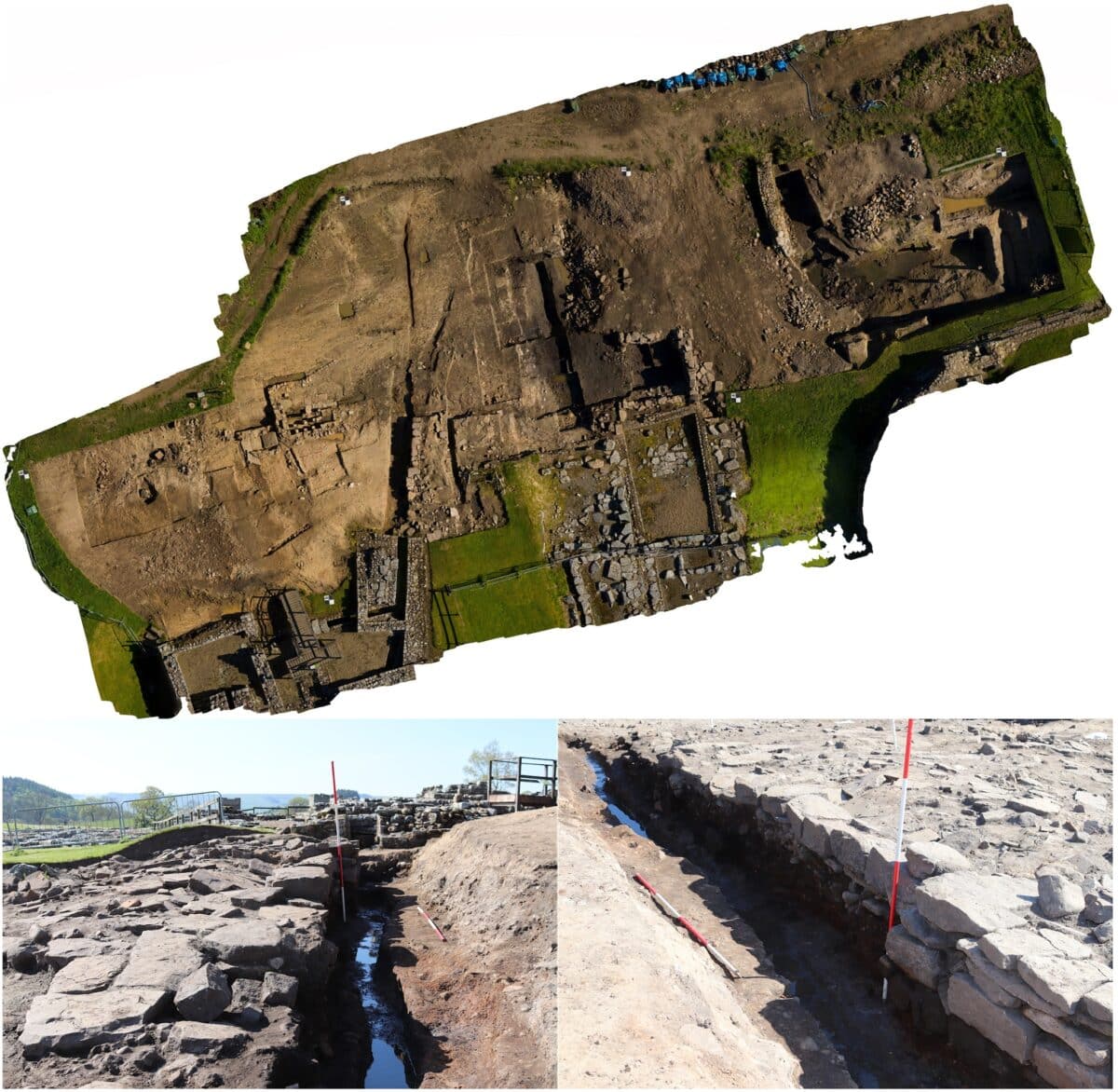

Archaeological excavations conducted in 2019 uncovered a third-century AD latrine drain connected to the fort’s main bathhouse. The structure collected human waste and transported it through stone-lined channels downhill toward nearby water sources.

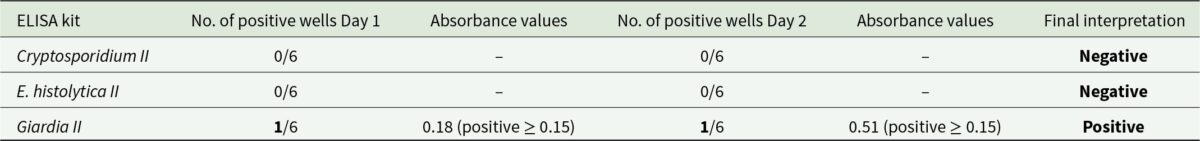

Fifty-eight sediment samples were taken from the length of the drain and tested using microscopy and ELISA assays. Researchers found parasite eggs in 28 percent of the samples. Ascaris appeared in 22 percent of them, Trichuris in 4 percent, and one tested positive for Giardia duodenalis.

All three parasites are spread through fecal-oral transmission. Contaminated drinking water, poorly handled food, or unclean communal surfaces are common routes.

The ELISA testing method followed strict replication criteria. Only one sample showed a positive result for Giardia, but it met all requirements for reliability. Researchers confirmed this finding through multiple test kits across two days, using both visual and quantitative metrics.

Parasites That Outlasted Roman Legions

Vindolanda was continuously occupied by Roman troops and civilians between the first and fourth centuries AD. The research team also analyzed sediment from an earlier fort ditch dating to the first century. That sample, like the later ones, contained Ascaris and Trichuris eggs.

This continuity indicates that intestinal infections were not an isolated occurrence. Instead, they appear to have been a persistent health issue for soldiers and camp followers over several generations.

Although Roman texts acknowledge the existence of intestinal worms, they provide little evidence of effective treatment. Individuals infected by helminths often experience prolonged symptoms such as fatigue, abdominal pain, diarrhea, and malnutrition. In military contexts, these symptoms could reduce combat readiness and physical endurance.

Latrines and baths at Vindolanda were intended to mitigate these risks. However, the discovery of parasite eggs throughout the drain system shows that infrastructure alone was not enough to prevent contamination.

Researchers noted that samples collected from a slower-flowing northwestern drain segment had higher concentrations of parasites. In contrast, a steeper northeastern branch had no detectable parasites. This variation suggests that water flow rates influenced where contaminants settled. Mapping of these patterns is provided in the visual data from the excavation study.

A Frontline Health Hazard, Replicated Across the Empire

The Vindolanda findings are consistent with parasite data from other Roman military forts such as Carnuntum in Austria and Bearsden in Scotland. Like Vindolanda, these sites show high prevalence of soil-transmitted helminths but lack the broader diversity seen in urban Roman settlements.

In cities like Londinium and Eboracum, archaeologists have recovered remains of pork tapeworms, fish tapeworms, and liver flukes. Urban diets, denser populations, and more complex trade networks likely contributed to a wider range of parasitic infections in those environments.

At Vindolanda, food records preserved on wooden tablets indicate pork was frequently consumed. Ascaris eggs are morphologically indistinct between humans (A. lumbricoides) and pigs (A. suum), leaving open the possibility of zoonotic transmission through the use of pig manure or shared waste facilities.

The Trichuris eggs found were consistent in size with the human-infecting species T. trichiura, although the researchers acknowledged that contamination from domestic animals near the drain could not be ruled out. Similar challenges have been addressed in other European parasite studies from Roman contexts.

What Ancient Pathogens Tell Us About Roman Resilience

The detection of Giardia duodenalis contributes to a growing body of evidence showing that waterborne pathogens circulated widely in Roman society. This protozoan has previously been identified in latrines from ancient Jerusalem, Roman Italy, and Turkey. Vindolanda’s case now adds Britain to the historical map of Giardia transmission.

Vindolanda’s preserved documents also mention other infectious conditions. One military report states that ten soldiers were unavailable for duty due to conjunctivitis. Though unrelated to intestinal parasites, this detail illustrates how contagious diseases affected unit strength and operations.

Parasite data from Vindolanda confirm that Roman military sanitation faced structural limits. Waste systems may have been impressive in design but fell short in practice when it came to protecting health at isolated frontier sites.

First Appeared on

Source link