Scientists Reveal Why the Green River Cuts Straight Through One of America’s Biggest Mountains

The Green River’s dramatic route through Utah’s Uinta Mountains has puzzled geologists for more than a century. Now, a group of researchers from the United Kingdom and the United States claims to have identified the powerful subterranean force that pulled the river through the rock: a deep Earth process known as lithospheric dripping.

Their findings offer a new explanation for how the Green River carved a 700-meter-deep canyon through a mountain range that stands 4,000 meters high. The study, led by Dr. Adam Smith of the University of Glasgow, proposes that the Earth’s crust beneath the mountains sagged millions of years ago, temporarily lowering the land and creating a pathway for the river to punch through.

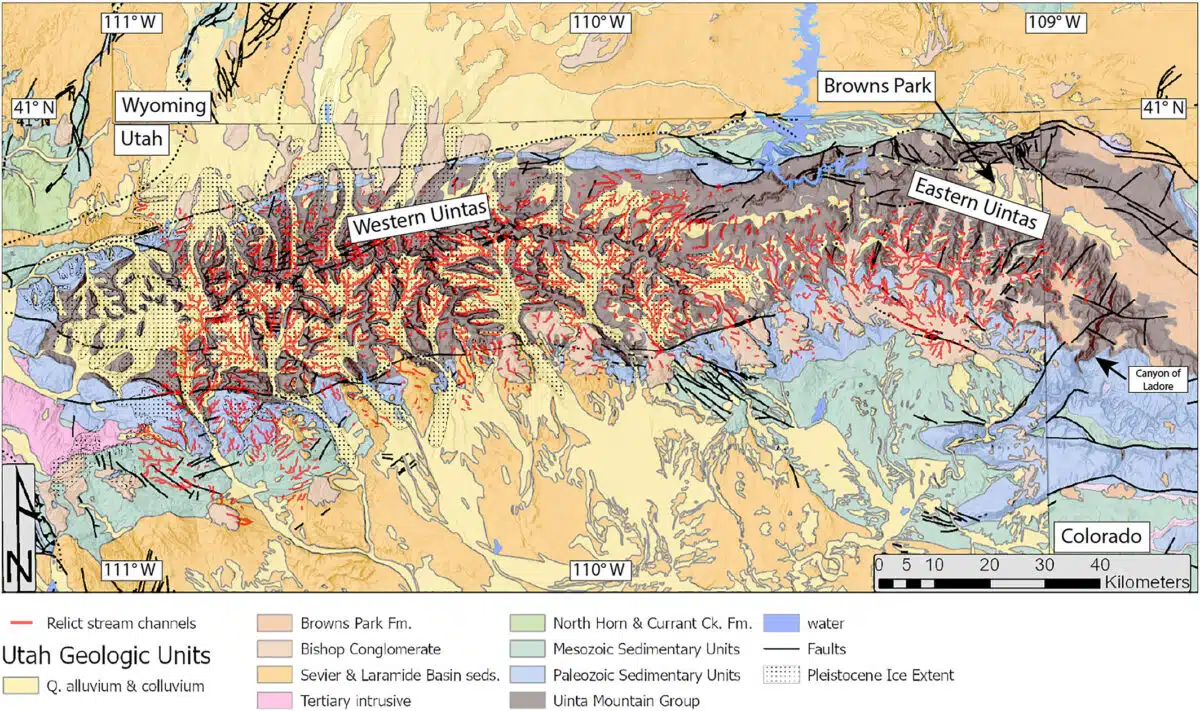

The Uinta Mountains, roughly 50 million years old, should have stood in the way of the Green River’s flow. Yet for the past 8 million years or less, the river has cut directly through them, creating geological features like the Canyon of Lodore and eventually merging with the Colorado River. The anomaly, long regarded as one of North America’s great geological riddles, may now have a conclusive answer. Researchers turned to seismic imaging and advanced modeling to trace the unexpected reshaping of the region’s topography.

A Drip Beneath The Crust

The theory centers on a geological event called a lithospheric drip, where dense material from the lower crust accumulates, then detaches and sinks into the Earth’s mantle. As the drip descends, it drags the surface downward, altering the landscape. According to Dr. Smith, the team identified a “cold, round anomaly” about 200 kilometers underground and between 50 to 100 kilometers across, interpreted as the remnant of such a drip.

“We think that we’ve gathered enough evidence to show that lithospheric drip, which is still a relatively new concept in geology, is responsible for pulling the land down enough to enable the rivers to link and merge,” he added.

This subsidence, they argue, created a temporary depression in the landscape. During this period, the Green River established its course across the depressed zone, cutting into the rock while the mountains above were still lowered. When the drip eventually broke off and continued sinking, the mountain range rebounded. By then, the river had already entrenched its channel.

The findings are supported by the detection of a “bullseye”-shaped uplift pattern around the Uinta Mountains, a surface fingerprint typically left behind after a lithospheric drip. The crust in the area is also several kilometers thinner than expected for a mountain range of that size, which the team interprets as further evidence that dense material once detached and fell away.

Seismic Tools and Advanced Modeling

To reach these conclusions, the researchers analyzed previously published seismic imaging data, a technique that tracks how earthquake waves travel through the Earth to reveal structures below the surface. This approach, similar in concept to a CT scan, allowed the team to visualize hidden anomalies deep beneath the mountains. As explained in the study, publised in Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, the team also relied on digital models of river networks to compare current elevations with reconstructed ancient topography.

Their calculations of how much surface uplift was caused by the missing crust matched closely with the roughly 400-meter change they inferred from river erosion patterns. This alignment between physical measurements and topographic modeling helped solidify their case that a drip event, not tectonic uplift or river capture from the south, explained the current landscape.

The research also rebuts previous theories, including the suggestion that the Green River might have existed before the mountains formed or that sediment deposits allowed it to overflow the range. As stated by Dr. Smith, none of those scenarios align as well with the observed geological structures or the timing of the river’s integration into the Colorado River system.

Far-Reaching Continental Effects

Beyond solving a regional mystery, the research underscores a larger shift in North America’s hydrology. The moment the Green River merged with the Colorado, it altered the continental divide, redrawing the line that separates rivers flowing to the Pacific from those draining into the Atlantic. In the study’s findings, this event reshaped watersheds and created new ecological boundaries that influenced the evolution of local wildlife.

Though the Uinta Mountains are in a tectonically quiet region, the findings suggest that deep mantle processes can dramatically reshape surface landscapes without the need for earthquakes or volcanic activity. The researchers emphasize that lithospheric dripping is still a relatively new concept in geoscience, and its role in shaping landscapes may be more widespread than previously thought.

“We hope that this paper will help resolve a longstanding debate about one of North America’s most significant river systems,” Dr. Smith said, “and help build the growing body of evidence that lithospheric drips may be the hidden answer to more tectonic mysteries than we’ve previously realized.”

First Appeared on

Source link