Enormous Pair of Deep-Earth Hot ‘Blobs’ Shape Earth’s Magnetic Field, Scientists Say

For all we’ve learned about places far away in outer space, we may have barely scratched the surface of the places lying deep within Earth. As a result, there’s a lot of information we seem to be missing out on—for example, the influence of two huge rock blobs on Earth’s magnetic field.

In a Nature Geoscience paper published yesterday, researchers announced that they’ve found evidence of two enormous blobs of solid, superheated material that appear to have shaped Earth’s magnetic field for millions of years. These big lower-mantle basal structures—blobs for short—lie at the base of Earth’s mantle, roughly 1,864 miles (3,000 kilometers) beneath Africa and the Pacific Ocean, study lead author Andrew Biggin explained in a commentary about the paper for The Conversation.

The continent-sized blobs are much hotter than the lower mantle, creating a significant temperature gradient in the rocky mantle. According to Biggin, a geologist at the University of Liverpool in the United Kingdom, this sharp contrast helps sustain the flow of Earth’s fluid outer core, referred to as the geodynamo.

“Without this massive internal heat transfer from core to mantle and ultimately through the crust to the surface,” Biggin wrote, “Earth would be like our nearest neighbors Mars and Venus: magnetically dead.”

The history of Earth’s magnetism

Earth’s magnetic field runs on electric currents generated by the motion of extremely hot iron and nickel—the geodynamo. To study historical trends in Earth’s magnetism, researchers look to the magnetic records contained in rocks and other natural materials. For instance, igneous rocks borne of cooled magma acquire a permanent magnetism that captures the direction of Earth’s magnetic field at the time and place of cooling.

While studying such rocks, Biggin and his colleagues noticed distinct patterns in the magnetic records of rocks up to 250 million years old. Specifically, the magnetic directions displayed strong correlations with the longitude and latitude of where the rocks presumably formed.

Meanwhile, geologists and seismologists in recent decades had increasingly focused on blobs, which appear to be closely related to volcanic eruptions. But Biggin’s team wondered whether the different puzzle pieces—magnetic records in volcanic rocks or blobs and volcanic eruptions—could help explain the role of blobs in Earth’s magnetic field.

Exploring Earth, bottom-side-up

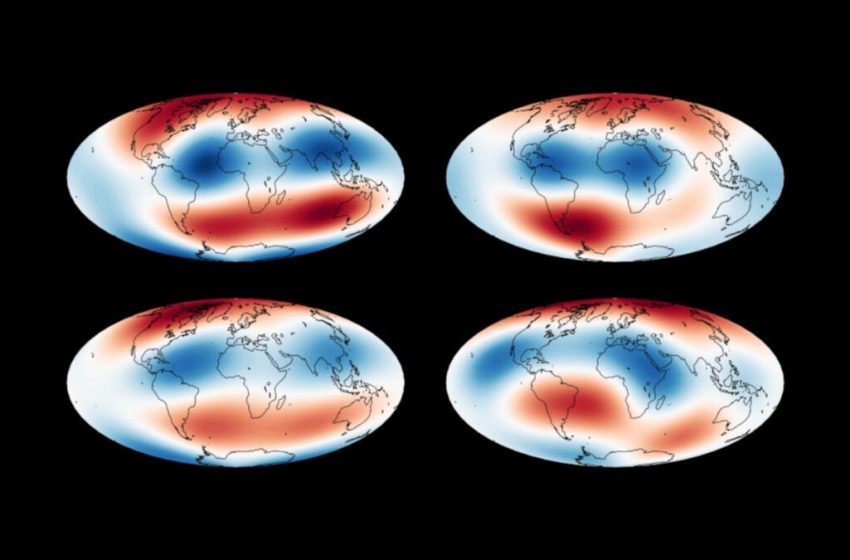

For the new research, the team developed advanced simulations that mapped out Earth’s magnetic field based on different heat profiles for the core, mantle, and blob. After several trials, the map that most accurately depicted Earth’s actual magnetic field represented the model that included strong variations in heat transfers—something that would be the case if the blobs were actively churning between the outer core and the lower mantle.

What’s more, the team found that the presence of blobs contributed to the overall stability of the magnetic field, with certain sections of the field remaining stagnant for hundreds of millions of years.

“What seems to be happening is that the two hot blobs are insulating the liquid metal beneath them, preventing heat loss that would otherwise cause the fluid to thermally contract and sink down into the core,” Biggin explained.

That said, blobs are still a general enigma for scientists; researchers have yet to properly characterize their true origin and identity. If the simulations are correct, however, blobs appear to be a big part of ensuring the Earth keeps things together—so “we have much to thank them for,” Biggin noted.

First Appeared on

Source link