Sex in space is happening, moving from theory to urgent reality

As spaceflight shifts from rare government missions to something closer to routine travel and work, one awkward question is getting harder to ignore: what happens to human reproductive health away from Earth?

A new report argues this isn’t sci-fi anymore – it’s “urgently practical,” especially as more people spend more time in space and commercial missions multiply.

Two revolutions are starting to collide

“More than 50 years ago, two scientific breakthroughs reshaped what was thought biologically and physically possible – the first Moon landing and the first proof of human fertilization in vitro,” said clinical embryologist Giles Palmer.

“Now, more than half a century later, we argue in this report that these once-separate revolutions are colliding in a practical and underexplored reality: space is becoming a workplace and a destination, while assisted reproductive technologies have become highly advanced, increasingly automated and widely accessible.”

The point isn’t to encourage anyone to try conceiving in orbit. The report’s message is more basic: the risks are foreseeable, the data are thin, and the rules are fuzzy.

Big gaps in standards, not just data

The authors say there still aren’t widely accepted, industry-wide standards for managing reproductive health risks in space.

That includes issues like accidental early pregnancy during travel, fertility effects from radiation and microgravity, and where the ethical boundaries should sit as space research expands.

They’re calling for a shared framework that pulls together reproductive medicine, aerospace health, and bioethics before decisions get made on the fly.

Space is rough on the body

The review describes space as “an increasingly routine workplace” but also “a hostile environment” for human biology.

The stressors aren’t mysterious: altered gravity, cosmic radiation, and circadian disruption are all known troublemakers for the body.

Animal studies suggest short-term radiation can disrupt menstrual cycles and raise cancer risk, but the authors say long-duration human data are limited, especially for male fertility. In fact, the effect of cumulative radiation on male fertility is described as a “critical knowledge gap.”

Further data is needed

One relatively comforting note is that data from female astronauts from the Shuttle era suggest later pregnancy rates and complications look similar to age-matched women on Earth.

But the report emphasizes that this doesn’t answer the harder questions about longer missions. It also doesn’t cover the growing group of private astronauts who may have very different health profiles and mission conditions.

The authors argue that longer-duration missions in both men and women will require new evidence “to guide diagnostic, preventive, and therapeutic strategies in extraterrestrial environments.”

Tech for human reproduction in space

Although pregnancy is currently a contraindication for spaceflight, and menstruation is often suppressed using hormonal methods, this approach reflects today’s operational limits rather than long-term biological certainty.

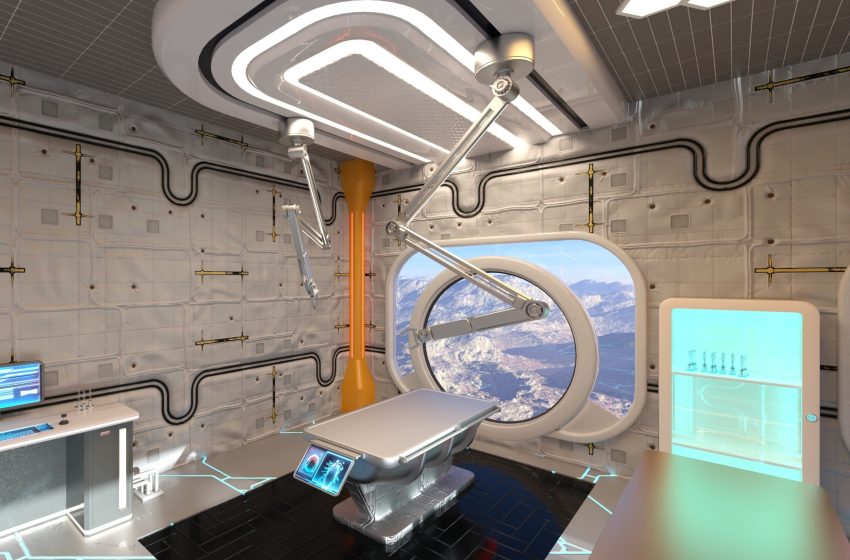

The report notes that advances in assisted reproductive technologies are making these tools increasingly automated and compact, raising the possibility that they could eventually meet the practical demands of space-based reproductive research and medical care.

“Developments in assisted reproductive technologies [ART] often arise from extreme or marginal conditions but quickly extend beyond them,” Palmer said.

“ART is highly transferable because it addresses situations where reproduction is biologically possible yet structurally constrained by environment, health, timing, or social circumstance, constraints that already exist widely on earth.”

Ethical planning can’t wait

Even if human reproduction in space still feels far-off, the report says ethical planning can’t wait.

It raises questions that sound simple until you picture them in a mission context: disclosure of pregnancy, genetic screening, informed consent for research, and responsibility if something goes wrong during a long flight.

“IVF technologies in space are no longer purely speculative. It is a foreseeable extension of technologies that already exist,” Palmer explained.

“Gamete preservation, embryo culture, and genetic screening are mature, portable, and increasingly automated. As human activity shifts from short missions to sustained presence beyond earth, reproduction moves from abstract possibility to practical concern.”

And the authors warn that these technologies tend to enter real-world practice “incrementally, quietly and often justified after the fact” – which is exactly why they want guardrails built now.

A policy blind spot

“As human presence in space expands, reproductive health can no longer remain a policy blind spot,” said Dr Fathi Karouia, a NASA research scientist.

“International collaboration is urgently needed to close critical knowledge gaps and establish ethical guidelines that protect both professional and private astronauts – and ultimately safeguard humanity as we move toward a sustained presence beyond Earth.”

The takeaway is less “space babies soon” and more: if space is turning into a normal place to work, then reproductive health needs the same kind of planning, standards, and ethics that we’d demand for any other extreme workplace.

The study is published in the journal Reproductive BioMedicine Online.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

First Appeared on

Source link