100-Year-Old Chemistry Law Proven Wrong Forcing Textbook Revisions Across the Globe

A long-standing boundary in organic chemistry has just been crossed. At the University of California, Los Angeles, researchers have synthesized a class of molecules that had, until now, remained a theoretical impossibility. Their creation marks a turning point in how chemists think about structural constraints at the molecular level.

The focus is a rare class of compounds known as anti-Bredt olefins. Due to their severe geometric strain, these molecules have defied synthetic access for more than 100 years. That changed in late 2025, when a team of chemists at UCLA demonstrated that under the right conditions, these high-strain intermediates can not only form, but also participate in useful chemical reactions.

The breakthrough opens new pathways in molecular design, particularly in areas where shape and spatial arrangement play a defining role — including drug development, materials science, and catalysis.

A Once-Impossible Molecular Structure, Now Within Reach

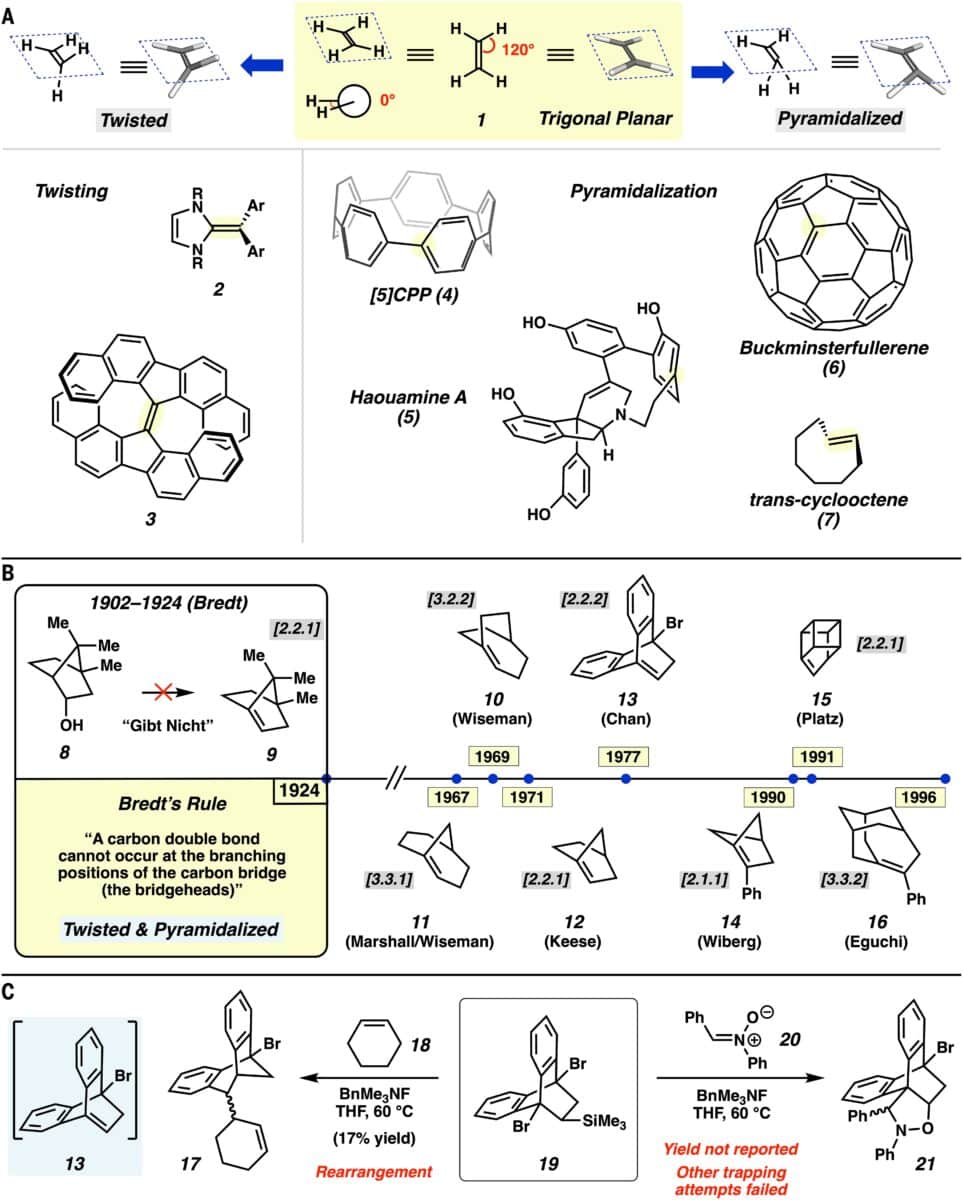

The origin of this development dates back to 1924, when German chemist Julius Bredt proposed that placing a double bond at the bridgehead of a bridged ring system was chemically prohibitive. The resulting angular distortion, he observed, would make such structures unstable and synthetically inaccessible. His conclusion became known as Bredt’s Rule, a foundational principle still taught in chemistry programs today.

But a century later, researchers led by Neil Garg, professor of chemistry at UCLA, developed a way to momentarily form these forbidden structures and trap them before they collapse. The process involves using a fluoride-induced elimination reaction on specially designed precursors, generating the strained intermediate just long enough for a second molecule to react with it.

Although the anti-Bredt olefin itself is too unstable to isolate, the team inferred its formation through the use of chiral starting materials. The final products retained their stereochemistry, strongly suggesting that the reaction passed through the strained geometry in a controlled, non-random manner. Computational modeling by co-author Ken Houk supported the plausibility of this intermediate under the reaction conditions.

The researchers detailed their methodology and findings in Science, showing that the reaction pathway works reliably and can be reproduced with variations in ring size and substitution.

Not Breaking the Rule, but Bending It with Precision

This study does not invalidate Bredt’s Rule altogether. Instead, it reframes it as a reliable general principle that admits exceptions when synthetic conditions are carefully controlled. For over a century, the rule’s strictness discouraged chemists from exploring certain molecular scaffolds. The UCLA team has now demonstrated that these neglected spaces in chemical space may be more accessible than once believed.

As noted in a feature from The Daily Galaxy, this kind of exception is not a minor footnote. It reshapes how chemists evaluate what’s structurally feasible and reopens areas of synthesis long dismissed as impractical or forbidden.

Garg addressed this shift directly in an official statement, saying that many researchers simply never attempted to work with anti-Bredt olefins because they assumed it could not be done. His team’s work now shows otherwise, opening the door to new classes of strained-ring systems that may play a functional role in molecular synthesis.

Flat No More: Why Shape Matters in Drug Discovery

One of the most immediate applications lies in pharmaceutical chemistry. The shape of a drug molecule plays a central role in its ability to bind to biological targets. Flat or symmetrical compounds often lack the structural diversity needed to interact selectively with enzymes, receptors, or protein surfaces.

![Structural Analysis Of [2.2.1] Abo 12 And Synthesis Of A Precursor For Abo Generation](https://isenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Structural-analysis-of-2.2.1-ABO-12-and-synthesis-of-a-precursor-for-ABO-generation-600x1200.jpg)

With the ability to generate non-planar, three-dimensional scaffolds, the UCLA method aligns with ongoing efforts in drug design to move beyond conventional flat molecules. These strained structures may provide new opportunities for optimizing drug candidates that can better fit the contours of biological macromolecules.

As highlighted in a recent report from Earth.com, the discovery could also influence other areas, from materials science to the design of high-performance polymers. In systems where molecular geometry governs reactivity or mechanical properties, controlled access to high-strain intermediates offers new design strategies.

Redrawing the Limits of Molecular Design

The publication of the UCLA study has already prompted labs in Europe and Asia to begin testing variations of the technique. Early attempts to generalize the approach to other bridged ring systems are underway, and several research groups are adapting the fluoride-triggered elimination reaction to generate new types of strained intermediates.

![Scope Of Trapping Reactions With [2.2.1] Anti Bredt Olefin 12](https://isenews.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Scope-of-trapping-reactions-with-2.2.1-anti-Bredt-olefin-12-1200x1154.jpg)

At the same time, the discovery is influencing how chemistry is taught. Faculty at several institutions are revising their presentations of Bredt’s Rule, emphasizing its role as a predictive tool rather than a rigid boundary. Instructors are integrating this new data into lectures on stereoelectronic effects, ring strain, and the kinetics of elimination reactions.

The UCLA study was carried out with contributions from graduate students and postdoctoral researchers Luca McDermott, Zachary Walters, Sarah French, Allison Clark, Jiaming Ding, and Andrew Kelleghan. Their combined work adds to a growing movement within chemistry to revisit and test the limits of long-held assumptions.

First Appeared on

Source link