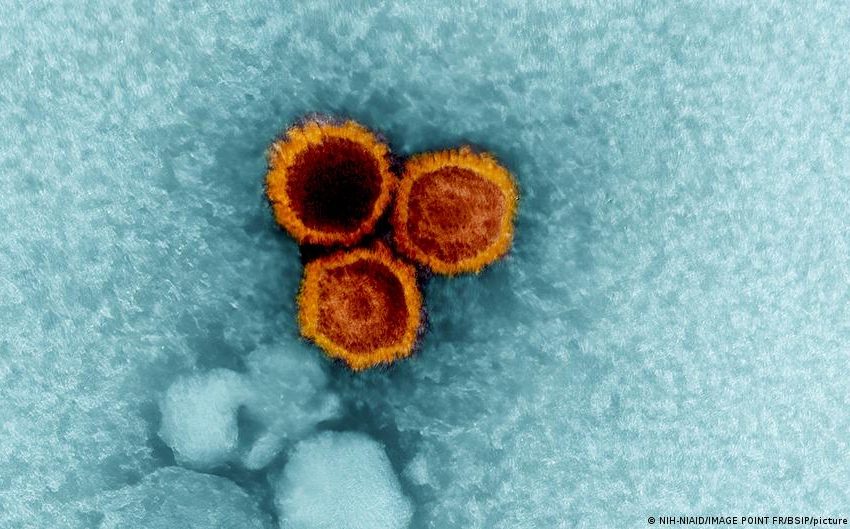

How the Epstein-Barr virus triggers MS in some people

The Epstein-Barr virus is a herpes virus and is considered a contributory cause of various cancer and autoimmune diseases. It is transmitted via droplets such as in saliva. That’s why one of the diseases caused by the virus, Pfeiffer’s disease, or Pfeiffer’s glandular fever, is also known as the kissing disease.

It has been known for a long time that the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) is also a contributing cause of multiple sclerosis. The problem, however, is this: Almost every human is infected with EBV and carries it in their body for life. Multiple sclerosis, however, affects less than 1% of the population. How is that possible?

Scientists may now have come closer to solving this mystery. The answer is, as often, hidden in our genes.

In people who suffer from MS, the immune system attacks the nerves

People who develop multiple sclerosis have a misguided immune system. Instead of attacking intruders from outside, it turns inward, against a person’s own body. Parts of the immune defense attack the myelin sheaths, which surround our nerve fibers like an insulating layer and which usually help to transmit signals.

People who have developed MS often suffer from vision and sensory problems. Initially, they’re unable to control their abdominal muscles, then the sphincter muscles of the bladder and bowel. Eventually, the muscles needed for breathing are affected as well.

The treatment of MS patients involves suppression of their immune system. It would, however, be much better to prevent the disease from breaking out in the first place.

How the Epstein-Barr virus massively increases the risk of developing MS

Scientists from China, Germany, Switzerland and the UK have now found out how the occurrence of the Epstein-Barr virus, in combination with a certain genetic constellation, leads to the development of MS.

The decisive factor could be a molecule called HLA-DR15. HLA molecules are an important part of our immune system. Like small human arms, they sit on the surface of particular cells and point out to the immune system what’s currently going on inside them, thereby helping our immune defense to differentiate between endogenous and exogenous structures.

When B cells (white blood cells that produce antibodies) are infected with the Epstein-Barr virus, they present parts of the virus to other immune cells, thereby arming the immune defense against the virus. This, however, poses a problem: The presented virus structures are very similar to a protein that is also found in the insulating layers around our nerve fibers. Deceived, the immune system is trained to attack the myelin protein.

Fatal similarity: When virus proteins imitate nerve tissue

The link between EBV and MS has been known for some time. Now, however, scientists have found out that the Epstein-Barr virus uses an even nastier trick when infected B cells have the HLA-DR15 molecule. In that situation, the virus modulates the infected cell in such a way that the cell itself presents the myelin protein.

This is astonishing, because “myelin has absolutely no place in a B cell,” said Roland Martin, who supervised the study. This means that the body of an MS patient is not accidentally, but deliberately programmed to attack itself.

However, HLA-DR15 cannot fully explain the mechanism behind developing MS. After all, only around every second person who develops MS has this genetic configuration.

Conversely, around every fourth person in northern Europe has HLA-DR15, and only a fraction of those develop MS. Therefore, the combination of genetic configuration and virus does not lead to MS automatically. It’s a building block that increases the likelihood of developing the disease. But it is “by far the most important genetic risk factor,” said Roland Martin.

The critical period: Why infections during adolescence are risky

For the development of MS, it’s decisive when a person undergoes an EBV infection. Late childhood and early adulthood are considered vulnerable periods.

In addition, an unhealthy diet, lack of vitamin D, smoking, pollution, working shifts or obesity can contribute negatively, according to Martin.

Why is there no vaccination against EBV?

MS specialists believe that a vaccination which prevents an initial infection with EBV is not possible because the virus is so well adapted to humans.

Preventing an outbreak of Pfeiffer’s disease after a person is infected with EBV would be rather more feasible. “This could presumably be achieved by a vaccination during early childhood, and it would be a huge plus,” said Roland Martin. If the kissing disease comes with symptoms, this increases the risk of developing MS later. Experts intend to intervene at an early stage to keep the disease under control.

When will the first vaccinations against the Epstein-Barr virus be available?

Initial vaccination candidates are being tested in trials. “A vaccination is currently a topic of very, very big interest,” Martin said. So there’s some movement on the issue after years of reluctance.

Martin’s team wants to use the recently discovered mechanism for possible treatments. It was currently working on specifically eliminating immune cells that present EBV parts or react to them, the scientist said. “Whether this works is another matter,” he concedes. “But we do have the necessary tools now.”

They’d only apply to MS patients who have the HLA-DR15 genetic package. But even that would be a big success in the fight against MS.

This article was originally written in German.

First Appeared on

Source link