What Scientists Discovered in This Remote Cave Was Buried for 3,700 Years, and It’s Finally Been Revealed

In a cave nestled high in the Calabrian mountains, ancient bones have revealed a shocking genetic discovery: a child born from a father-daughter union over 3,700 years ago. The rare finding, backed by DNA analysis, is the earliest confirmed case of this kind in prehistoric Europe.

The discovery comes from Grotta della Monaca, a burial cave high in the Calabrian mountains, where researchers studied the scattered remains of 23 people who lived between 1780 and 1380 BCE. The site helped them piece together ancient family ties and daily life in a community that, until now, had remained completely silent.

DNA Exposes a Family Twist

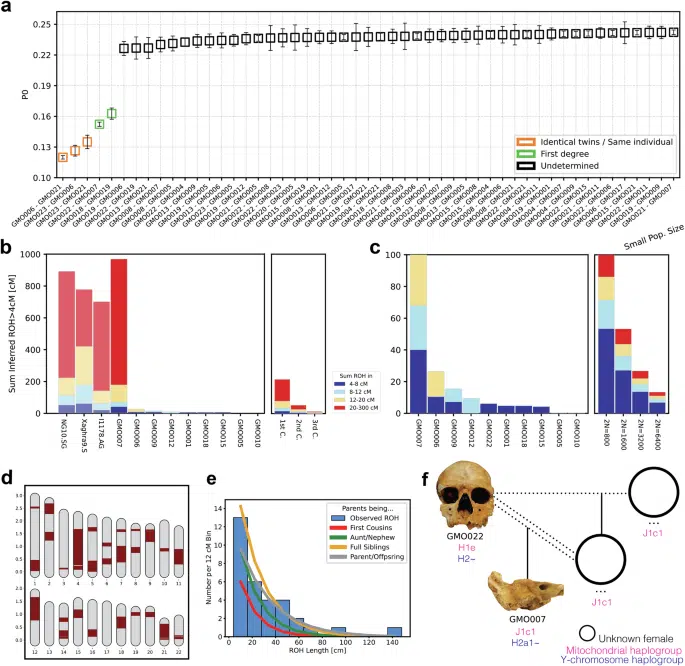

To rebuild family trees from the cave, the team compared long stretches of shared DNA between individuals. That’s when one child’s genome raised a red flag: the boy had so many identical genetic blocks on both chromosomes that only a parent-child or sibling-sibling pairing could explain it.

Turns out, the child was born from a father and his daughter, according to the team led by Dr. Francesco Fontani at the University of Bologna. The mother’s remains weren’t identified, but the child’s DNA told the story clearly enough.

The team also noticed how relatives were often buried near each other. Mothers lay close to their children, and one burial area mostly held women and young people, with just one adult man in the mix.

Connected To Sicily, But With Their Own Identity

Even though the cave is tucked away in the Calabrian hills, the people buried there weren’t isolated.

“Our analysis shows that the Grotta della Monaca population shared strong genetic affinities with Early Bronze Age groups from Sicily, yet lacked the eastern Mediterranean influences found among their Sicilian contemporaries,” Fontani explained.

According to the study, published in the journal Communications Biology, two individuals had links to northeastern Italy, meaning people were likely moving across long distances, even through tough terrain. So despite the remote location, the community seemed to be part of wider regional networks.

The site gave researchers a long-term view, since caves like this often serve as burial places for generations. That made it possible to trace how family, mobility, and culture played out over centuries in one small place.

Eating Dairy Without the Right Gene

One of the more surprising findings came from comparing genetics with diet. Most of the adults didn’t have the gene that lets people digest milk as adults, yet their bones showed clear signs of regular dairy consumption.

So how did they manage it? Likely by turning milk into yogurt or cheese, which lowers the lactose content and makes it easier to digest. According to Dr. Donata Luiselli, one of the study’s senior authors, this shows how cultural solutions came before genetic evolution. This small community seemed to know how to adapt and survive in their landscape, relying on herding and dairy even when their bodies weren’t built for it.

“This exceptional case may indicate culturally specific behaviours in this small community, but its significance ultimately remains uncertain,” pointed out Dr. Alissa Mittnik of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

First Appeared on

Source link