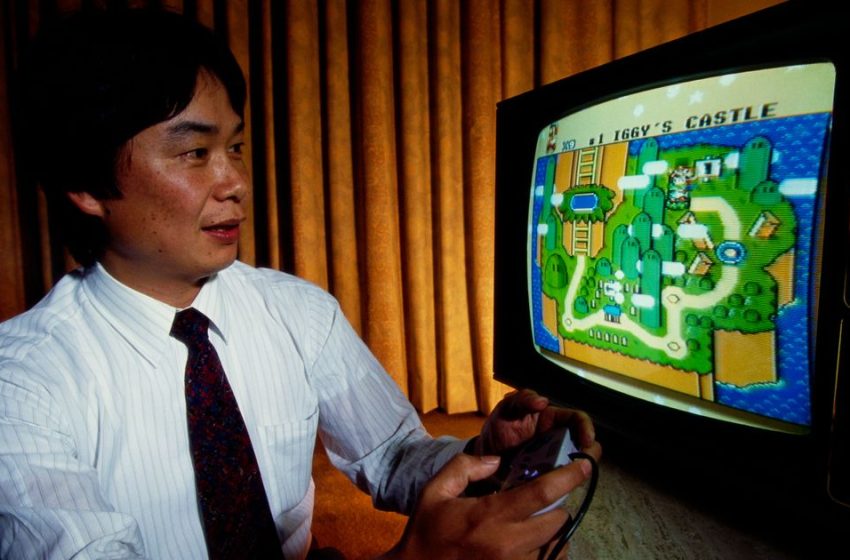

Shigeru Miyamoto’s Focus on Play

Photo: Ralf-Finn Hestoft/Corbis via Getty Images

Nintendo is secretive.

Typically, this truth — a perpetual frustration among gaming journalists and historians — surprises the casual video-game player. Perhaps, as I once did, you imagine that the latest Mario and Zelda games are being concocted in a Wonka-esque factory tucked cozily between Kyoto alleyways. That foreign travelers can take a guided tour of the video-game factory, one that, not unlike an American microbrewery, ends with a tasting menu of gaming delights.

In reality, Nintendo’s Japanese HQ is a bland office building that nonemployees rarely enter and few details find their way out. Keza MacDonald is one of the tiny number of English-speaking journalists to step inside. She reports seeing little to no signs of magic — just glass, white walls, and the occasional dash of intellectual property, like Mario’s mushroom power-up, to reassure guests that, yes, they are in the right place.

MacDonald is the author of Super Nintendo: The Game-Changing Company That Unlocked the Power of Play and the senior games editor at The Guardian, making her (as best I can tell) the only editor at a major newspaper covering the medium as their sole beat. Wielding that status and two decades of experience, she’s the rare reporter to have spoken with many leaders of Nintendo’s design team, often multiple times.

Yes, she’s chatted with legendary game designer Shigeru Miyamoto, but also producers, directors, artists, and corporate leaders. Her subjects have made every significant creative decision, from the plan to smash together the company’s handheld and console businesses to the inspired epiphany that every Nintendo character can and should fight one another in a battle to the death — generations before Fortnite.

Readers of Super Nintendo will enjoy those deep dives with unfamiliar artists and execs, but it’s Miyamoto and his creations that serve as the entry point into the company. In an early chapter of the book, excerpted here, MacDonald gives you a tour of the mind that imagined Mario, Zelda, Pikmin, and plenty more.

If Nintendo keeps a padlock on its secrets, then Miyamoto’s mind is a bank vault. Fans have long rumored that Nintendo requests Miyamoto not share details of his life for fear that they will serve as a sort of creative fuel, that competitors mustn’t have access. I can’t speak to that conspiracy theory, but I can share this anecdote. In my first roundtable interview, I asked the industry icon how his outdoor adventures as a child influenced his design philosophy as an adult. The room fell silent, including the translator, who I noticed wasn’t, well, translating. From across the table, a publicist, wearing a smile that cut across his face, murmured, “We don’t ask Miyamoto-san about his life.” So I asked which Koopaling was Bowser’s favorite.

MacDonald has done something no English-speaking reporter has before her: told the story of Nintendo, in detail, from beginning to end. She has gotten inside the mind of Miyamoto, the doors of Nintendo’s headquarters, and the intangible miasma that has made Nintendo and video games what they are today.

If you’d like to hear more, listen to my interview with Keza MacDonald on Post Games. We chat about Nintendo’s turbulent early days and the young talents who have already filled the shoes of Miyamoto.

I first met Shigeru Miyamoto in 2012, right before the release of the Wii U console. He was in Paris to receive the Prince of Asturias Award, also given to people like Václav Havel, Umberto Eco, and Annie Leibovitz. I had a cold from hell and was uncharacteristically nervous about speaking with him. Here was a person whose work had helped define not just Nintendo but the entire concept of video games: how they work, what they do, how they ought to make us feel. He has had a hand in every Nintendo console ever released (he even designed the casing for the later models of the Color TV-Game) and all of its major games. Few people in the world have had such an impact on culture, and yet Miyamoto is a rather unassuming character, easy to talk to, and fascinating to listen to. He dislikes the spotlight; despite appearing often over the years on conference stages or in Nintendo broadcasts to announce new games, he is not someone who enjoys putting his face to his work. Unlike Metal Gear Solid’s Hideo Kojima, he is no self-styled auteur, but his influence is vast — you will not find a game developer working anywhere in the world today who is untouched by it.

According to Iwata, who was one of his closest friends and collaborators, Miyamoto is almost uniquely able to understand both the technical and artistic sides of games development, whether he’s looking at the design of a console or the games that we’re going to play on that console. “It’s as if one second he’s using a magnifying glass, and the next instant he’s looking down from 10,000 feet overhead,” Iwata wrote. Miyamoto has never formally studied computers, programming, hardware, or electronics, but working side by side at Nintendo with people who specialize in these things, he has acquired a deep understanding of what computers are good at and what they’re not good at, what’s possible and what’s not — and, as Mario co-designer Takashi Tezuka told me, if he’s told something isn’t technically possible, he will reply with, “What would make it possible?” Since the earliest days of his career he has been pushing Nintendo’s programmers to do things that haven’t been done before.

His ability to understand the principles of programming and work with them, rather than seeing his design or artistic vision as something that’s in opposition to the limitations of technology, is key to that sense of wholeness that the best Nintendo games have, the feeling that every element of the game is feeding into the same goal: making the player feel good. “This kind of game designer is something of a rarity,” Iwata said. “When our games take this kind of an approach, regardless of whether Miyamoto is involved, they achieve an extremely high production quality, and if you zoom in on the individual details, you’ll find the finished product to be stunning.”

The second time I meet Miyamoto, it is a few days after his seventy-first birthday, in November 2023. We are in a meeting room in Nintendo’s modern headquarters, a mid-rise white building just south of Kyoto central station that few journalists have ever been inside of. He takes a while to warm up to our conversation, but when he does, it’s because we’re getting into the most minute details of hardware and software design. He lights up talking about the placement of the buttons on the GameCube controller. People who have worked with him are full of stories about times when he simply couldn’t let go of something until it was perfect. There have been times, he admits, when he’s made tiny changes even after designs were sent out to factories.

He cares enormously about whether the player is having fun, and judges the success of everything by this metric. It doesn’t matter if what’s on the screen is his idea or someone else’s. If it isn’t fun, it goes. In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, Miyamoto was frequently known to appear suddenly at the desk of a random Nintendo employee from a different team, hand them a controller, and without further explanation bid them to play something he was working on. He would watch closely over their shoulder, silent, seeing where they got confused, which directions they missed, where they smiled in satisfaction after a tricky section of a level. It was a much more hands-on approach to

playtesting than handing off a build of a game to a quality assurance team and waiting for a report.

“Miyamoto makes his games by taking leaps of faith: if we do this, here’s what we can expect,” Iwata wrote of his friend and colleague. “In that sense, he has a much higher batting average than most, but he is not omnipotent, and makes his fair share of mistakes … [He believes] that if a customer fails to understand what to do, he has failed. What sets Miyamoto apart is that despite being extremely stubborn when it comes to his designs, he’ll watch a person play a game for the first time with extreme equanimity. He’ll see how they react, and if he decides they’re missing the point, he’ll go back to the drawing board and try a fresh approach.” Iwata called this process “upending the tea table” or “knocking down the house of cards” — and Miyamoto’s colleagues know it could come for them at any time. But rather than scrap ideas, Miyamoto has a talent for figuring out how to make them better, and what can be salvaged — another thing that Iwata always admired. “Those inclined to knock down the house of cards are often overeager to scrap everything, but Miyamoto firmly believes that it would be a waste of time to throw it all away.”

When I’ve talked to Nintendo developers over the past couple of decades, they’ve painted Miyamoto as a kind of creative North Star for the company — and sometimes an intimidating presence. He is not shy about passing harsh judgment on game prototypes. Zelda programmer Shiro Mouri remembers a meeting in the early development of 2013’s A Link Between Worlds where the team presented their work to Miyamoto: “As soon as we started the presentation, I could clearly see Miyamoto-san’s facial expression rapidly darkening. I thought, This is bad … And then at the end he said, ‘This sounds like an idea that’s twenty years old,’ [and] that was the final blow. We were down on the floor.”

Miyamoto stayed deeply involved in the day-to-day business of game design for decades, until 2015, when he took the title of “creative fellow” — but even after that he would still pass judgment on projects in development. “Sometimes he doesn’t even hint at a smile. But even when he’s not showing his emotion in his face, I can see he is concentrating,” said longtime Nintendo creative director Shinya Takahashi, when I spoke to him in 2018. “If he says something’s good, it’s rare, and you know it is. Recently he’s been saying things are good on several occasions, I should say. He’s actually a shy person — even when he thinks something is well done, he would not often say that to someone directly.” (“I have never once been praised by Mr. Miyamoto,” reflected his colleague Hisashi Nogami ruefully at this point in the interview. “Behind your back he says he’s very pleased,” Takahashi reassured him.)

Miyamoto likes the phrase “as clear as day”: That is what he is searching for when he evaluates games, his own or others’. But he also believes that players can be trusted to work things out, to find the fun. “Miyamoto and I feel the same about this,” the Zelda series’ longtime producer Eiji Aonuma once told me. “If players reach their goal easily, it’s not really a very exciting game. A game should be something where users try to solve the puzzles and try to overcome something and get a feeling of achievement from the experience. But if it’s too difficult, if we don’t actually give enough hints, then at some point they’re not going to be interested in playing the game anymore. That balance is always important, between difficulty and hand-holding. There was a certain period [at Nintendo] when people thought that games should make it easier to progress and go forward. But Miyamoto and I think that’s not the core part of the fun of a game. Sometimes just getting lost in a game can be really good as well.”

Personally, I think one of the things that makes Miyamoto a great game designer is his enormous range of interests. A curious person, he has fallen into many hobbies over the years. He plays guitar, he loves baseball, he swims, he gardens — and he draws upon these things for his games. Nintendogs, the hit Nintendo DS game that gave players a virtual pup to take care of like a fluffy Tamagotchi, was based on caring for his own dog. Pikmin, the tremendous series of strategy games about a miniature spaceman commanding an army of tiny plant people around gardens, was inspired by his gardening fascination. His childhood play experiences in rural Sonobe made their way into Zelda.

These days, having handed over the work of game design to younger people at Nintendo and taken charge of the company’s creative collaborations, he is pursuing a great project of self-education on movies, reading scripts and studying the business to help Nintendo get the most out of its film partnerships. He was personally involved in the design of the Mario theme parks at Universal Studios in Osaka, LA and Florida — and, as ever, he is obsessed with the details.

“With game design, having that big idea, that grand design, is very important — but so is the polish,” Miyamoto told me in 2023. “As a designer, because I want to make something high quality, I take pride in the details. First off, having that major design direction and understanding and being sure that it’s a new concept, a good concept, is something that I want to feel. Once I’m settled on that, I like to fixate on the details. I like both aspects, and that is very compatible with developing games: the novel big picture and also the minute details, making sure everything’s as good as it can be.”

For Miyamoto, that good idea often comes from a character, just as it did for Donkey Kong. He had been doodling Mario for years before any of the rest of us heard about him; the same is true for the juvenile hero of the Zelda series, Link, and for the diminutive garden creatures that we know as Pikmin. All Mario’s games are built around his unique ability: He was the first video game character ever to jump.

“[The games] result from a continuous investigation of [characters’] traits, until finally they become extravagant, or can hold their own for all their simplicity,” observed Iwata. “We call this Miyamoto Magic. But if you asked Miyamoto, he’d say he’s merely using common sense and working through things carefully.”

From SUPER NINTENDO: The Game-Changing Company That Unlocked the Power of Play, by Keza MacDonald, published by Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of The Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC on February 3, 2026. Copyright © 2026 by Keza MacDonald.

Want to be emailed about sales and other updates to your saved products?

Success! You’ll get an email when something you’ve saved goes on sale.

Yes

Photo: Penguin Random House

Nintendo’s fourth president, the late Satoru Iwata, is credited with revitalizing the company he took over in 2002, overseeing the launch of the Nintendo DS and Wii consoles.

Pitched by a young Miyamoto as a way to repurpose arcade cabinets from an underselling Space Invaders knockoff, Donkey Kong was “the first video game whose form was determined by its characters, not the other way around.”

First Appeared on

Source link