Can flickering lights and sound slow Alzheimer’s?

Can Alzheimer’s disease be slowed by flickering lights and sound?

That is the question that drives Annabelle Singer, an associate professor and biomedical engineer at Georgia Institute of Technology and Emory University.

In her lab on Tech’s campus in Atlanta, Singer is trying to better understand patterns of neural activity in the brain and what goes wrong with Alzheimer’s patients. Building on that knowledge, she hopes to develop new ways to treat the disease.

“We are taking a really different approach to Alzheimer’s,” she said. “We’ve determined how neural activity that is essential for memory fails in Alzheimer’s disease. We’re then using that information to develop brain stimulation that could improve brain health.”

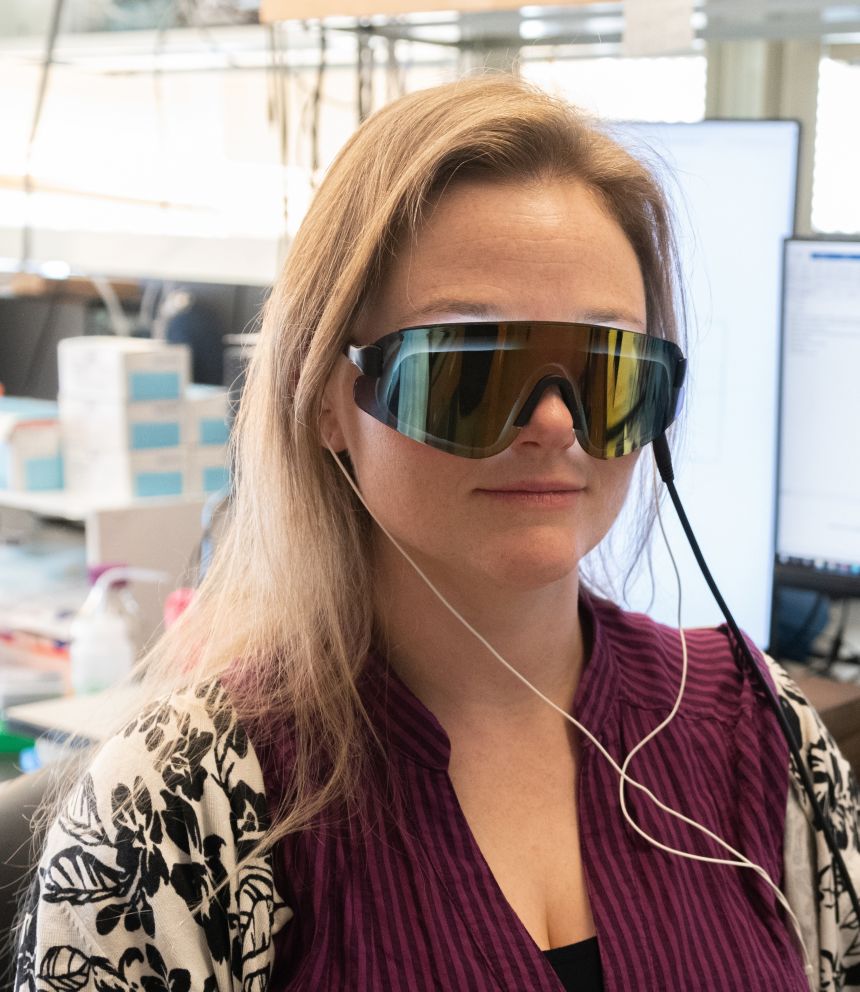

While pharmaceutical companies are investing tens of billions of dollars in research into drug therapies for the disease, Singer has set out on a completely different course: in the form of what looks like ski goggles and headphones.

The goggles deliver flickering lights at a rate about five times faster than your average strobe light while headphones pipe in a fast-clicking, beeping sound. By doing so, Singer is trying to decode memory in Alzheimer’s patients, using light and sound to explore how neural activity failures lead to memory impairment.

It’s a non-invasive form of sensory stimulation that has shown promise in preclinical studies and a feasibility study. Those preliminary tests found that flickering lights and sound at 40 Hz for an hour a day had the potential to slow cognitive decline and volume loss in parts of the brain vital for memory.

“Both those things are really promising,” she said. “We don’t know that we can reverse the memory impairment that’s already there. Instead, what we’re going for is to slow the continuing decline.”

Singer has long felt medications to treat Alzheimer’s carried too many potential serious side effects without a very good efficacy rate. She wanted to know if there was a different way.

“The majority of research on Alzheimer’s disease focuses on the molecular scale — how proteins accumulate or go wrong,” she said. “We’re asking, how do neurons behave electrically to generate memory and how do those patterns change in Alzheimer’s patients?”

A Phase 3 double-blind clinical trial is currently underway with nearly 700 patients participating at 70 different locations around the United States. The study is being led by Cognito Therapeutics, a medtech company specializing in wearable devices. Singer doesn’t drive the studies, but she serves as a scientific adviser on Cognito’s board.

“The hope,” she said, “is that we will see people who are undergoing this stimulation have slower or no decline in cognitive function than people who are not getting treated.”

The clinical trial, she said, is expected to be completed later this year.

More than 7 million Americans age 65 or older live with Alzheimer’s disease. That figure is expected to nearly double to 13.8 million by 2060 barring any medical breakthroughs. Worldwide some 57 million people have dementia, of which Alzheimer’s is the most common form according to the World Health Organization.

With an aging population, the need for more and better treatment is driving research around the world.

In recent years, the US Food and Drug Administration fast-tracked the approval of new medications lecanemab and donanemab, with some doctors expressing skepticism whether the modest improvement seen in clinical trials was worth the risk as both can trigger life-threatening swelling or bleeding in the brain.

Lecanemab slowed decline by 27% at 18 months compared with those who were not on the drug; people with mild cognitive decline on donanemab had about a 35% lower risk of disease progression.

The hefty price tag of around $30,000 a year for the therapies has also raised criticism as not being an option for most people.

A slew of next generation research continues, with the Mayo Clinic saying last April, “future Alzheimer’s treatments may include a combination of medicines.”

Not far from Singer’s lab at Georgia Tech, James Lah is director of the Cognitive Neurology Program at Emory University and an associate professor of neurology.

He collaborated with Singer on the initial proof-of-concept study a couple of years ago, evaluating 10 patients with mild cognitive impairment who underwent the flickering lights and sound testing for an hour a day over eight weeks.

“This was the first human trial of this technology in this approach,” he said.

What they found was that the flickering seemed to have a beneficial effect, in both testing of patients’ spinal fluid and from their electroencephalograms (EEGs), or brain-wave tests.

“We saw some really interesting changes in the patterns of electrical connectivity in patients after being exposed to this flicker,” Lah said.

That study helped lay the groundwork for the Phase 3 trial that is underway. Lah is not a principal investigator on the current trial, but he finds Singer’s work and the potential treatment really interesting.

A love of lights and sound

Ever since she was a teenager, Singer was drawn to lights and sound.

Raised in the small town of Boxborough, Massachusetts, a community of about 5,500 about 25 miles northwest of Boston, Singer thought she would enter the world of theater, working on set design.

Her high school didn’t have a robotics team or sophisticated engineering groups. What it did have was a theater. She was sucked in, not by the acting, but by the stage lights and importance of sound — and getting it all to work in unison.

“To me, the thing that makes the magic in theater is all the sets and the lights and the sounds,” she said. “It creates another world. I love that. I still love that.”

She would eventually become a biomedical engineer, attending Wesleyan University in Connecticut, followed by graduate studies at the University of California San Francisco and post-doc work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Her life changed about 20 years ago while attending rounds with doctors at the UCSF Fein Memory and Aging Center. She saw up close Alzheimer’s patients and the detailed set of tests they underwent.

“It was a really educational experience for me,” Singer said, “because I saw both how sophisticated all their work was. At the same time, they had almost nothing to offer their patients.”

That lack of treatment options, she said, left an indelible impression. “I was like, ‘Wow, there’s a huge gaping hole in how we’re addressing Alzheimer’s,’” she said. “That’s something that I’d like to work on.”

She hasn’t stopped in the two decades since. Her love for light and sound has come full circle, helping shape her innovative approach and her desire to help the millions with Alzheimer’s.

“In theater, it was like controlling how people perceive this stage,” she said. “In neuroscience research, it was controlling how one individual has a very controlled experience that then you can measure their reaction to it.”

Her research, she said, is built on decades of established science that have shown that flickering lights can affect neural activity in visual brain areas. But, she said, the visual cortex is not the brain region that “you’re going after in Alzheimer’s, so we had to innovate more.”

“Ultimately, we found light and sounds together at 40 Hz,” she said, “could reach the hippocampus, one of the brain regions that’s essential for memory.”

The most common side effect in the feasibility test was headaches. In another test of people with seizure disorders, she said the flickering lights didn’t lead to seizures, but rather “we actually saw a decrease in the subclinical seizure activity.” Her research as to why continues.

For Alzheimer’s patients, she understands the importance of drug research, but she added that “in my mind, it hasn’t addressed how we get to learning and memory impairment.”

“One of the things that we’re really excited about is how accessible this potential intervention is,” she said, referring to the potential goggles. “If we have a very safe, low-risk intervention, then I think that changes the equation.”

Time will tell if her research holds up under the ongoing clinical trial.

Lah, the Emory neurologist, said he’s intrigued by the work and what he’s seen so far.

“The whole notion of using external stimulation to modify brain activity is fascinating,” Lah said. “It’s just cool. I mean, certain things are just cool.”

First Appeared on

Source link