Buried for 30,000 Years, One Ice Age Traveler’s Toolkit Is Altering Human History

The hills of South Moravia have yielded thousands of Stone Age artifacts over decades of excavation, most of them anonymous fragments of a distant past. But a cluster of 29 stones found in 2021 at the Milovice IV site presents archaeologists with something different: the possibility of seeing a single person.

The stones were not scattered in the way discarded debris normally settles. They lay packed together, still in the configuration they would have held if wrapped in a leather or bark container that rotted away thousands of years ago. Radiocarbon dating of charcoal from the same layer places the deposit between 30,250 and 29,550 years before the present, a period when Gravettian culture extended across central Europe.

What makes the find matter, based on a detailed study published in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology, is that this appears to be the complete personal gear of one individual, not the accumulated trash of many people over generations. The distinction opens a rare window into how an Ice Age hunter actually moved through the world, what tools they considered essential, and how they coped when resources ran short far from home.

A Bundle Preserved in Time

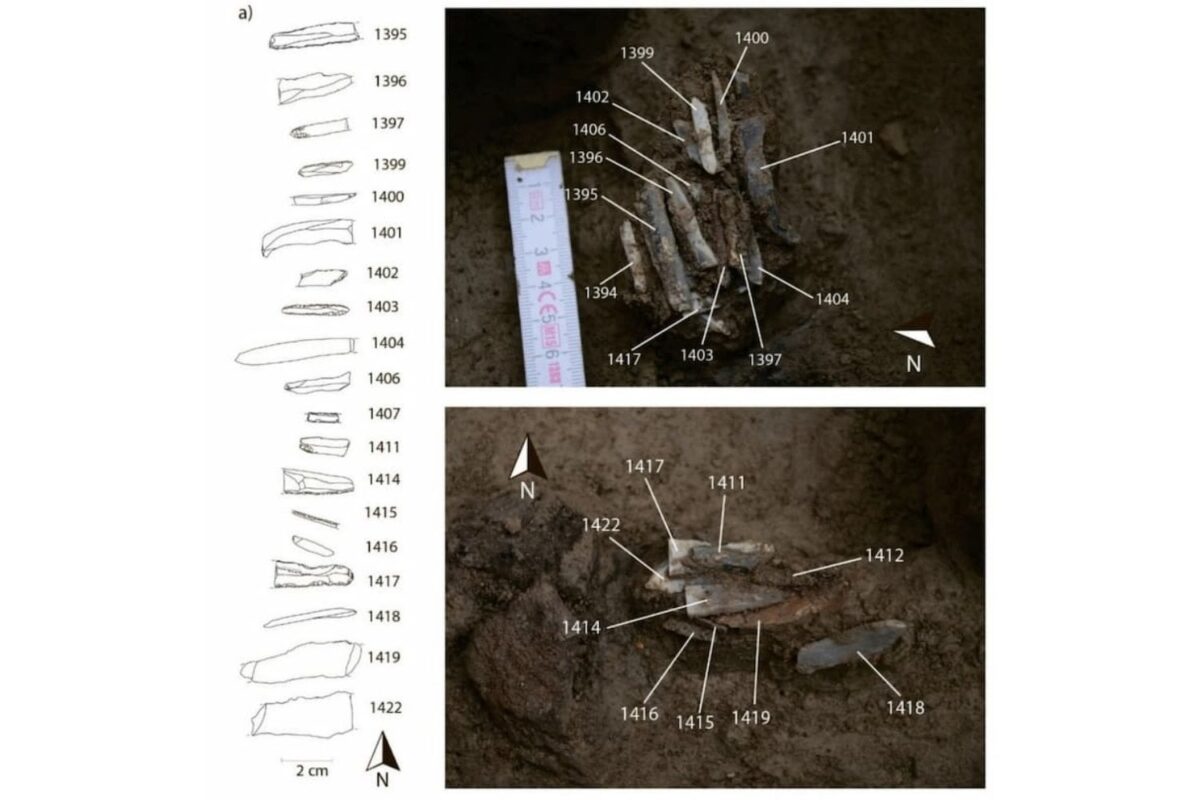

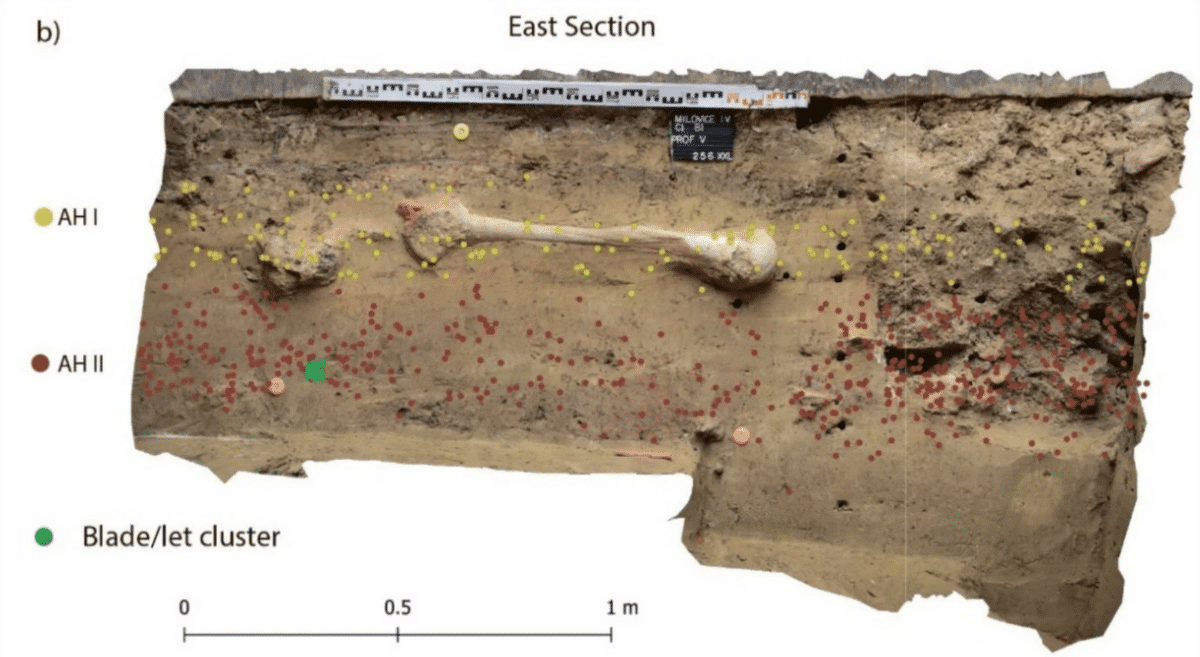

The excavation at Milovice IV in 2021 uncovered a complex stratigraphy spanning multiple Upper Paleolithic occupations. The toolkit emerged from Archaeological Horizon II, a layer that also contained a fireplace and animal bones dominated by horse and reindeer. The researchers documented the cluster’s position using a total station and excavated it in three phases with detailed photo documentation, preserving the spatial relationships among the 29 blades and bladelets.

“The specific context suggests that the items were originally bundled together in a container made of a perishable material,” the study in the Journal of Paleolithic Archaeology states. The absence of such material today is expected; organic preservation is rare in open-air sites of this age.

The horizon’s formation appears to have been relatively rapid. “It seems that the main body of AH II was deposited rapidly, likely shortly after, or even during, the human occupation of the site,” the authors note. This timing helps explain how a bundle of tools could remain intact rather than being scattered by later activity.

Reading the Edges of Stone

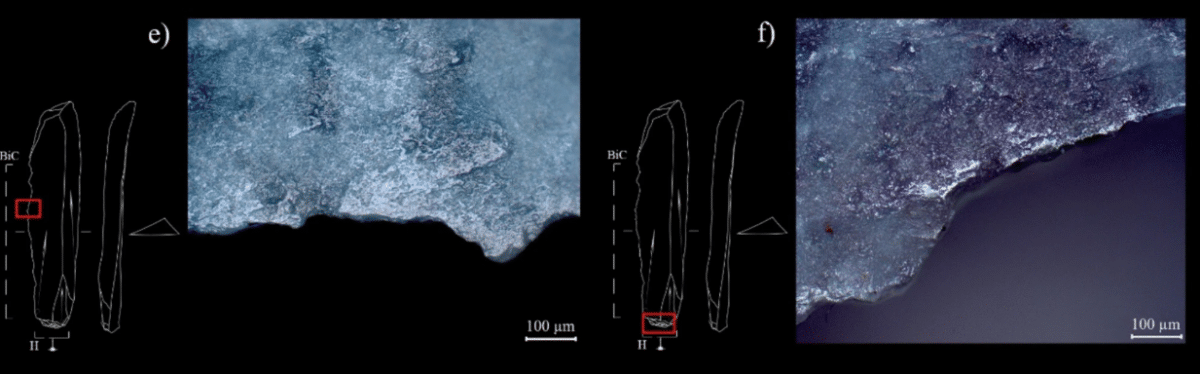

Techno typological and use wear analyses conducted at Sapienza University in Rome and the University of Hradec Králové identified multiple functions across the assemblage. “A substantial share of the assemblage exhibited fractures typically associated with projectiles, while other tools showed evidence of cutting, scraping, and drilling,” the research team reported.

The tools were made from raw materials of diverse origins, traced through laser ablation inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Some stone came from sources more than 100 kilometers distant. “The variety of raw materials reflects the mobility range or network of contacts of the individual,” the study explains.

The collection shows evidence of intensive use and modification. Broken pieces had been resharpened and repurposed into different tool types. “The use of small and broken pieces and spalls also indicates that at some point the personal gear was treated economically, likely due to a pressing shortage of raw materials during hunting or migration trips,” according to the analysis.

Dominik Chlachula of the Institute of Archaeology of the Czech Academy of Sciences, the study’s first author, told Live Science in an email that the artifacts “likely highlight an episode in the life of one person, which is ‘very rare’ for the Paleolithic.” In the same correspondence, he noted that such discoveries “may shed light on the behavior of prehistoric people during migrations or hunting trips, which did not tend to leave behind many traces in the landscape and are therefore practically invisible to archaeologists.”

The World the Hunter Walked

The Gravettian culture, which extended across Europe from roughly 33,000 to 24,000 years ago, is known for large mammoth bone dwellings, complex stone technology, and the carved female figurines called Venus statuettes. The people who occupied sites like Dolní Věstonice and Pavlov, near Milovice IV, lived in a cold steppe environment and hunted herd animals including horses, reindeer, and mammoths.

“Their economy was based on hunting and gathering, but they developed complex cultural, technological and social behaviour with long distance connections,” Chlachula said in the Live Science interview.

The Milovice IV toolkit fits within this broader pattern while adding individual scale. The diversity of raw material sources supports the inference of long distance movement or exchange. The intensive recycling documents decision making at the level of a single tool user facing real constraints.

The bundle’s discovery in a residential camp, among hearths and butchered bones, places the individual within a social setting even as the tools themselves speak to solitary foraging or hunting trips away from that base. Coverage from New Scientist describes the find as showing what an ancient hunter carried in a pouch, emphasizing the personal nature of the assemblage.

If the artifacts had been found separated, “they would not have stood out from the other discarded or worn out artifacts commonly found at the Milovice IV site,” the study notes. “It is the context which makes them interesting.” The 29 blades and bladelets now reside in laboratory storage at the Czech Academy of Sciences, available for continued study as researchers work to refine their understanding of site formation processes at Milovice IV.

First Appeared on

Source link