Common Eye Bacteria Linked to Faster Dementia and Alzheimer’s Progression

The bacterium that causes pneumonia does not remain confined to the lungs. For years, researchers have suspected it might travel elsewhere, though definitive evidence of where it goes and what it does upon arrival has remained elusive. A study published in late January now places that pathogen directly inside the human eye.

The finding centers on Chlamydia pneumoniae, an intracellular bacterium carried by a majority of the population at some point in their lives. In most people, it causes nothing more than a cough. In others, based on the new data, it may contribute to the destruction of the brain.

The research, conducted by a team at Cedars-Sinai Health Sciences University and detailed in Nature Communications, does not claim that bacteria cause Alzheimer’s disease outright. It suggests something more subtle: that a chronic, smoldering infection can amplify the disease once it has begun, accelerating both the pathology and the cognitive decline that follows.

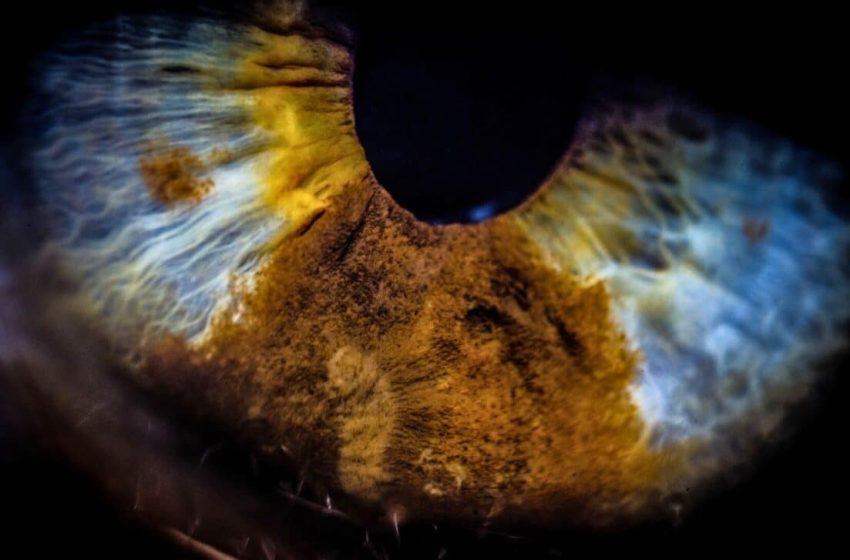

A Pathogen in the Retina

The researchers examined retinal and brain tissue from 104 donors, including individuals who had died with normal cognition, mild cognitive impairment, or full Alzheimer’s dementia. Using a monoclonal antibody specific to Chlamydia pneumoniae, they identified bacterial inclusions in the retina ganglion cell layer and inner nuclear layer, areas critical to visual processing. Quantification revealed a pattern: Alzheimer’s patients carried roughly twice the bacterial load of cognitively normal controls, and the highest levels correlated with the most severe brain pathology.

This relationship held across multiple verification methods. Fluorescence in situ hybridization detected bacterial genetic material directly. Giemsa staining showed the characteristic dark blue inclusions in the same retinal layers. Quantitative PCR confirmed the presence of the Chlamydia pneumoniae specific arginine repressor gene in tissue samples.

The study’s lead author, Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui, a professor at Cedars-Sinai, framed the finding in terms of consistency. “Seeing Chlamydia pneumoniae consistently across human tissues, cell cultures and animal models allowed us to identify a previously unrecognized link between bacterial infection, inflammation and neurodegeneration,” she said in a statement. The Cedars-Sinai newsroom published an overview of the findings, noting the potential for developing noninvasive diagnostic approaches.

How the Bacterium May Worsen Disease

Identifying the bacterium in retinal tissue answered one question but raised another: what, if anything, is it doing there? To address this, the team turned to laboratory models. Human neuronal cells infected with C. pneumoniae responded by activating the NLRP3 inflammasome, a multiprotein complex that serves as a central switch for inflammatory signaling.

Once triggered, the inflammasome cleaved pro-caspase 1 into its active form, which in turn processed interleukin 1 beta into its mature, pro inflammatory state. Downstream, the researchers observed gasdermin D cleavage, a molecular event that precedes pyroptosis, a form of programmed cell death distinct from apoptosis.

The infected neurons also produced more amyloid beta, the peptide that aggregates into the plaques characteristic of Alzheimer’s disease. In transgenic mice engineered to develop Alzheimer’s like pathology, chronic C. pneumoniae infection worsened cognitive performance on behavioral tests compared to uninfected controls. The mice accumulated more plaques, showed more neuroinflammation, and died more quickly, a sequence the authors describe as disease amplifying.

Not every retina mounted an effective defense. The researchers noted a relative deficit of pathogen engaged microglia in Alzheimer’s tissue, suggesting that the eye’s immune surveillance system may fail as the disease progresses. This finding aligns with the observation that individuals carrying the APOE4 gene variant harbored significantly higher bacterial loads than those without it.

A Pathway to Treatment

Timothy Crother, a research professor at Cedars Sinai Guerin Children’s and co corresponding author of the study, pointed directly to the translational potential. “This discovery raises the possibility of targeting the infection inflammation axis to treat Alzheimer’s,” he said in a prepared statement.

Anti inflammatory drugs targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome are already in clinical development for other conditions and could be repurposed for Alzheimer’s. Antibiotics capable of clearing C. pneumoniae from neural tissue offer a more direct approach, though questions about tissue penetration and treatment duration remain unresolved.

The study leaves several questions open. It remains unclear how the bacterium reaches the retina. Respiratory infection provides an obvious portal, but whether the organism travels through the bloodstream, crosses the blood brain barrier, or ascends via olfactory or trigeminal nerves is not established. The timing of infection is similarly opaque. Inoculation could occur decades before cognitive symptoms emerge, making intervention windows difficult to define.

The Eye as a Window to the Brain

The retina is the only part of the central nervous system visible from outside the body, and advanced imaging techniques can resolve individual cell layers noninvasively. The study’s finding that retinal bacterial load correlates with brain pathology raises the possibility of using the eye to diagnose or monitor the disease without lumbar puncture or positron emission tomography.

Maya Koronyo-Hamaoui emphasized this point. “The eye is a surrogate for the brain, and this study shows that retinal bacterial infection and chronic inflammation can reflect brain pathology and predict disease status, supporting retinal imaging as a noninvasive way to identify people at risk for Alzheimer’s.” Whether such imaging can detect the bacterium itself or must rely on downstream inflammatory signatures remains a subject of ongoing investigation.

The research, funded by the National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, now moves toward prospective studies. The current data are cross sectional, capturing a single moment at the end of life. Longitudinal work will be required to determine whether bacterial load precedes cognitive decline or merely accompanies it. For now, the bacterium identified in retinal tissue represents a confirmed biological correlate of Alzheimer’s pathology.

First Appeared on

Source link