Why NASA Picked A Boeing 747 To Piggyback The Space Shuttle

The Boeing 747 has taken many forms in its decades of service. First introduced in 1970, the Queen of the Skies has flown for airlines all over the world. It has also had a handful of side gigs over the last 55 years, serving as the iconic Air Force One, a command and control post, and even an airborne firefighter. Some proposals got as crazy as Boeing’s idea to transform the 747 into a flying aircraft carrier. While that never made it past the study phase, NASA would eventually take advantage of the jet’s low-wing profile and clean tail configuration to give the plane the job of carrying an aircraft unlike any other — the space shuttle.

For three decades, the iconic space shuttles were the flagships of American spaceflight. In their 135 missions, the five shuttles set major milestones, including putting the first American woman into space and launching spacecraft deep into the reaches of our solar system. They deployed and repaired the Hubble Space Telescope, which gave us views of our universe that had never been seen before. Most notably, they helped unite nations as the workhorses behind the construction of the International Space Station.

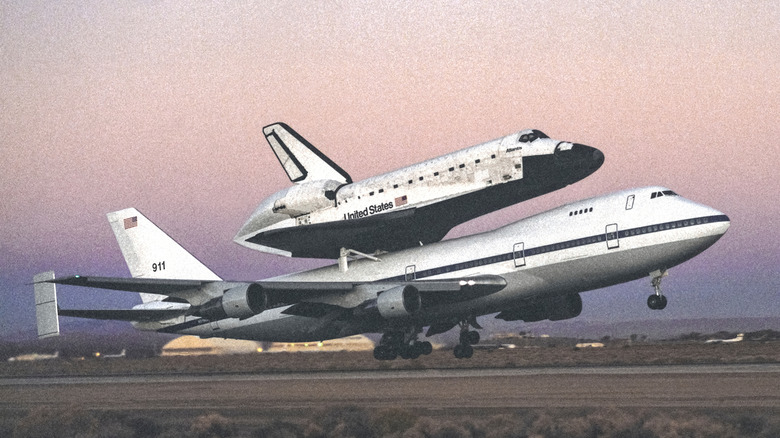

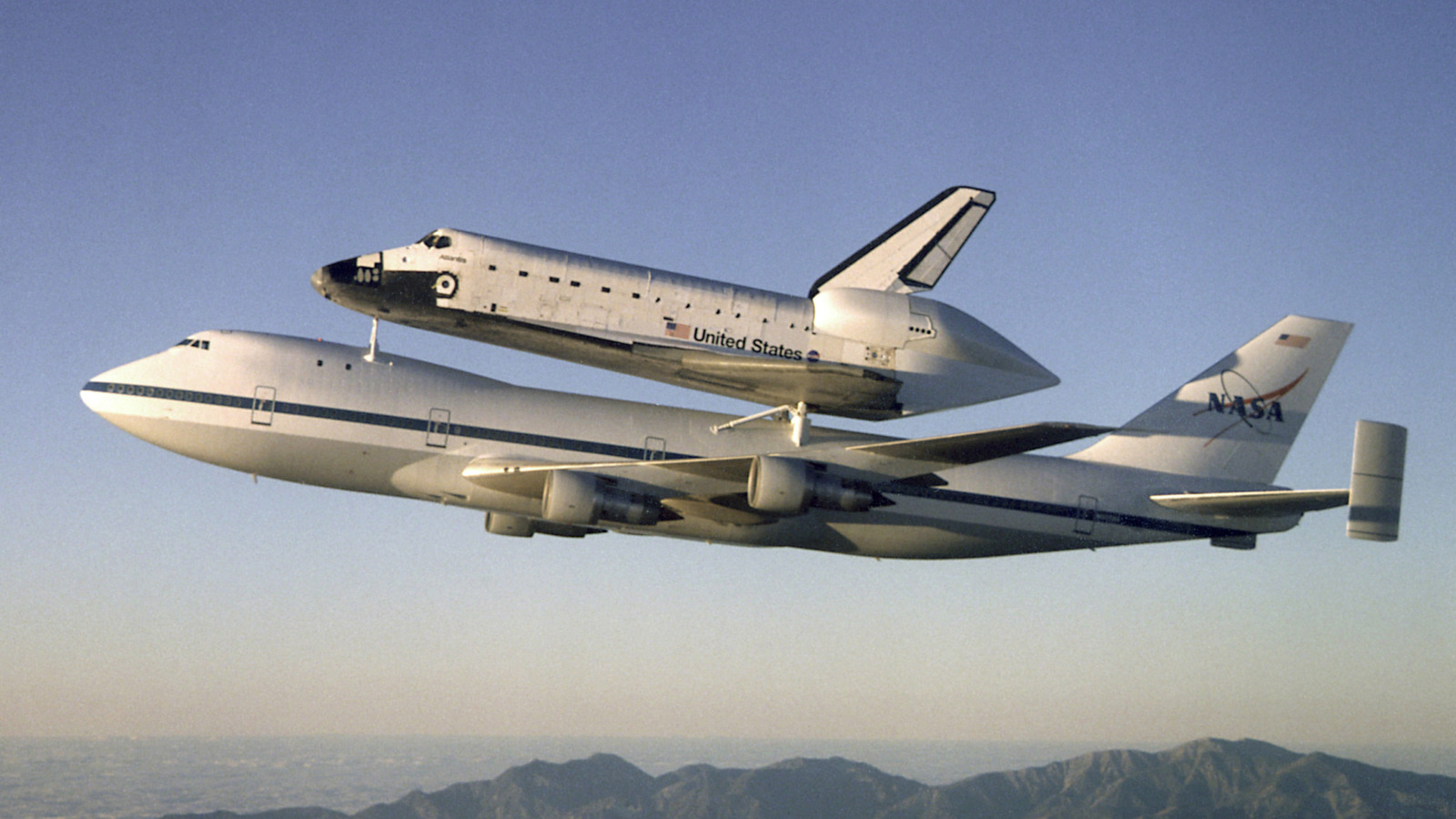

However, none of these missions and moments would be possible if it weren’t for a pair of hot-rodded Boeing 747s. While five orbiters could carry 8 tons of cargo into low Earth orbit before gliding back home, only two jumbo jets could get them back in position for their next mission. Meet the 747 Shuttle Carrier Aircraft, or SCA.

Need a lift?

Each of the shuttle’s 135 missions started at Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral. That’s an easy trip to make if the shuttle lands back in Florida, but 54 times, weather diversions forced a landing at the backup site of Edwards Air Force Base in California. If things really went off kilter, emergency abort landing sites were prepared along the East Coast and across the Atlantic. NASA quickly realized it needed a way to get its shuttles back to Florida, and its cavernous Apollo-hauling Super Guppy was far from big enough to carry them.

For the SCA, NASA landed on the two biggest planes on the market: Lockheed’s C-5 Galaxy military transport or the Boeing 747. Boeing’s low-wing design and tail configuration were preferred, so it was deemed most suitable to have an orbiter riding piggyback. In addition, any C-5 would be loaned to the agency from the Air Force, while NASA could have full ownership of a 747. That made the Queen of the Skies the easy choice.

To mount the orbiter to the back of the plane, three struts would be installed on top of the fuselage, utilizing the same attachment points the orbiter used to secure the orange external fuel tank at launch. However, having a shuttle on the back of the jet obstructed airflow to the vertical stabilizer, so two additional stabilizers were installed on the tail section to increase stability.

Inside the jet, a plethora of modifications were made to allow the 747 to carry an extra 170,000 pounds of space shuttle. Alongside structural reinforcement of the fuselage, insulation, seats, and inner panels were stripped from the inside of the jet to save weight. Only the first class seats remained on board to haul NASA personnel during missions.

Alpha and omega

NASA and Boeing began transforming a former 747-100 into the first of the carriers in 1974. Formerly flying for American Airlines, the first SCA, dubbed NASA 905 would play a pivotal role in the development and testing of the shuttle, as it would get the shuttle airborne during the Approach and Landing Tests. A series of missions in 1977 saw the shuttle and 747 separate mid-air, letting the orbiter glide back down to earth for its first ever flights.

After testing, the SCA began hauling shuttles that landed in California back to Cape Canaveral. Although far quicker than any rail or overland transportation, the delivery was far from simple. Upon landing, over 170 engineers had to help load and unload the shuttle from the back of the SCA. That orbiter also made the 747 incredibly cumbersome. While most 747s could easily fly from New York to London, the orbiter cut the range of the SCA to about 1,000 miles, with speed and ceiling limited to just Mach .6 and 15,000 feet. The limited range meant returning a shuttle to Florida took as long as three days.

Thankfully, help was on the way. In 1989, a 747-100SR acquired from Japan Airlines would begin the modification process to enter service as NASA 911. Together, the two planes would fly the shuttles from Pacific to Atlantic a combined 87 times during the Shuttle Program, allowing them to get spaceborne once more in a matter of months.

After their final missions in 2011, the SCAs would take the remaining three shuttles to their retirement homes in museums across the nation, marking an end to one of NASA’s most beloved programs and the two Boeings that kept them alive.

First Appeared on

Source link