Single-cell spatial proteomics maps human liver zonation patterns and their vulnerability to disruption in tissue architecture

Human tissue collection

Human tissue was acquired with written, informed consent under a National Institutes of Health Institutional Review Board-approved protocol (NCT01915225) from two distinct patient populations. Healthy liver samples (N = 14) were obtained from patients undergoing risk-reducing total gastrectomy for germline CDH1 mutation(s), who consented to research liver biopsy during surgery. These patients had hereditary diffuse gastric cancer syndrome but no evidence of liver pathology. Desmoplastic samples (N = 4) were obtained from patients with metastatic liver disease undergoing surgical resection, representing regions adjacent to but distinct from metastatic lesions. The tissue procured was characterized by either a normal or tumour–normal margin based upon visible inspection and confirmation of the final histopathologic examination. Following tissue procurement, which was completed roughly within 20 min of incision, tissue was fixed in 1% PFA in PBS for 48 or 72 h, washed in PBS and incubated in 30% sucrose in PBS for at least 24 h before embedding in OCT. OCT blocks were stored at −80 °C. No statistical methods were used to pre-determine sample sizes. The cohort size (18 individuals) represents a substantial increase compared with previous scDVP studies examining spatial trajectories, which analysed up to three mice or six human individuals17,18. The number of cells per trajectory (44 hepatocytes) was chosen to provide double coverage of the approximately 20 hepatocytes spanning a human liver lobule, ensuring robust spatial representation. Throughout the paper, uppercase N denotes the number of independent biological samples (individuals), while lowercase n represents the number of observations (cells, proteins or measurements).

Histology staining and assessment

Haematoxylin and eosin, Oil Red O and Masson Trichrome histological staining were performed on liver sections for pathological assessment using standard protocols by the Molecular Pathology Unit, National Cancer Institute. Histopathological assessment was performed by a single pathologist and the detailed report can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Cryosectioning, tissue mounting and immunofluorescence

Two-micrometre polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides (MicroDissect) were pre-treated by ultraviolet exposure at 254 nm for 60 min to improve tissue adherence. Directly following ultraviolet treatment, sequential washing steps were performed on the slides: first in 350 ml of acetone, then in a solution of 7 ml of VECTABOND reagent (Vector Laboratories; catalogue number SP-1800-7) diluted in 350 ml of acetone, followed by a brief 30-s rinse in ddH2O. Slides were then dried under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. Next, 10-µm-thick liver sections were thawed once and cut onto pre-cooled glass or polyethylene naphthalate membrane slides using a Leica cryostat (Leica CM1950) for histology or DVP purposes, respectively. The slides were stored at −80 °C.

For immunofluorescent staining, the slides were thawed at room temperature followed by a 2-min fixation with 4% PFA in PBS at 37 °C. The tissue was then permeabilized using 95% ethanol in ddH2O for 2 min at room temperature, rehydrated with PBS and blocked with 5% BSA in PBS for at least 15 min at room temperature. Following this, sections were incubated with primary antibody GS (abcam; catalogue number ab176562; clone #EPR13022(B); 1:300) overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the sections were washed, three times for 15 min each, with PBS and then incubated with the secondary antibody and fluorescent dyes phalloidin (Thermo Fisher; catalogue number A30104; 1:300) and Sytox Green (Thermo Fisher; catalogue number S7020; 1:500) for 1 h at room temperature. The following day, the sections were washed, three times for 15 min each, with PBS and then incubated at 4 °C overnight with primary antibody ASS1 (abcam; catalogue number ab170952; clone #EPR12398; 1:100) conjugated using Zenon Rabbit IgG Labeling Kits (Thermo Fisher; catalogue number Z25307; 1:20 relative to microlitres of ASS1 used). The next day, after an additional three washes, for 15 min each with PBS, the slides were left unmounted and stored at 4 °C until shipment.

A similar immunofluorescence protocol was used to validate protein distribution. Primary antibodies UGT2B7 (ProteinTech; catalogue number 16661-1-AP; polyclonal; 1:50), AMDHD1 (OriGene; catalogue number TA809954; clone #OTI1D4; 1:250) or RPS3 (abcam; catalogue number ab128995; clone #EPR7808; 1:100) were incubated overnight at 4 °C. The next day, the sections were washed, three times for 15 min each, with PBS and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500) and fluorescent dyes DAPI (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalogue number H3570; 1:1,000) and phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific; catalogue number A22287; 1:300) for 1 h at room temperature. After an additional three washes, for 15 min each with PBS, the slides were mounted in the dark overnight in preparation for imaging.

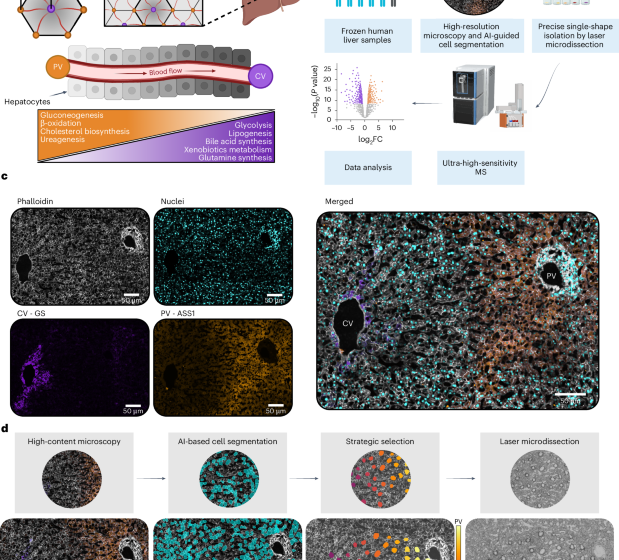

High-resolution microscopy, image processing and quantification

For scDVP, confocal image acquisition was performed using a PerkinElmer OperaPhenix high-content imaging system equipped with a ×20 air objective (numerical aperture 0.8). The system was operated through Harmony software v.4.9, with images collected using 2 × 2 binning and 10% overlap between adjacent tiles. For each sample, a single focal plane was manually selected and maintained across all channels. To eliminate channel crosstalk, fluorophores were excited sequentially, with the following acquisition parameters: CFP at 80% laser power and 100-ms exposure, Alexa 488 at 30% power and 20-ms exposure, Alexa 568 at 80% power for 40 ms and Alexa 647 at 60% power for 40 ms. Post-acquisition flat-field correction was applied through the Harmony v.4.9 software platform. Image reconstruction was accomplished using scPortrait33, with the phalloidin–CFP signal used as the reference channel for calculating tile positions. These positions were subsequently applied to all channels to generate one tif file per channel per sample. Stitching parameters were set to 0.1 for tile overlap, with filter sigma and maximum shift values of 1 and 50, respectively.

Immunofluorescence images for validation of loss of zonation profiles were acquired using a Leica SP8 inverted confocal laser scanning microscope, a ×63 (1.4 numerical aperture) oil objective, a zoom of 1.00 and a pixel resolution of 1,024 × 1,024. The tile scans were merged using the Leica software and further processed using Imaris (Bitplane 9.9.0) and Image J34. Fluorescence intensity ratios or intensities normalized to area were plotted.

Identification and strategic selection of single cells

The processed and stitched images were imported into the Biological Image Analysis Software (BIAS) using the packaged import tool and retiled to 1,024 × 1,024 pixels with 10% overlap. The region of interest in each image was selected. Cell segmentation was performed externally using a custom-trained Cellpose segmentation model (Cellpose v.2.0) on the phalloidin staining channel35. The resulting masks were imported into BIAS where duplicates were removed. Three characteristic reference points were selected based on prominent tissue features per image. Contours and reference points were exported as .xml files. The contours were subsequently simplified by removing at least 90% of the data points defining the contour’s shape.

In this study, only cells belonging to one defined zonation trajectory per patient were analysed. These were selected in an automated fashion: first, portal and central veins were automatically detected in the images using a custom algorithm by which areas with no cells were identified. A Gaussian blur and morphological dilation was applied to the image to remove small voids and subsequently was thresholded using the filters .threshold_minimum function from the skimage package. Central and portal veins were then identified by the expression of the marker proteins GS and ASS1, respectively. All encountered veins were grouped by the algorithm in non-overlapping trajectories, defined by a pair of portal and central veins. The trajectory of interest was selected manually. Defined regions of interest were automatically generated, including all cells segmented directly between the veins and up to an angle of 65 degrees within the axis defined by the centre of both veins (Extended Data Fig. 1). Cells to segment were then chosen such that the minimum distance between any two shapes was maximized by solving a combinatorial optimization problem known as remote-edge diversity maximization using the farthest-first traversal algorithm19,20. Up to 44 non-overlapping shapes per pair of central and portal veins were selected to be cut via laser microdissection for further processing. For each of the selected cells, the spatial ratio S was calculated, as \(S=\frac{{d}_{{\rm{portal}}}}{{d}_{{\rm{portal}}}\,+\,{d}_{{\rm{central}}}}\), with dportal the distance (for example, in pixels) from the centre of the shape at hand to the portal vein and dcentral the distance to the central vein. The values from 0 (here close to the central vein) to 1 (here close to the portal vein) are covered uniformly by the selected shapes. To facilitate this analysis workflow, we developed a GUI where users need only to select two points of interest—point A (central vein) and point B (portal vein). An XML file containing the coordinates of the 44 cells along that trajectory is generated automatically by the GUI, enabling straightforward downstream analysis. Generally, only trajectories between clearly identified central and portal veins were analysed. This strategic cell selection approach has since been further developed into CellPick (cellpick.app), a comprehensive web-based tool for flexible spatial sampling in diverse tissue contexts.

Laser microdissection

Following image alignment using three manually selected tissue reference points (tissue characteristics seen in bright field), cell contours were imported and isolated using a Leica LMD7. The system was operated in a semi-automated manner controlled by the LMD v.8.3 software and using the following optimized parameters: ×63 objective, power of 51–56, aperture 1, speed 10, middle pulse count 1, final pulse 0, offset 100, head current of 50–56% and pulse frequency set to 2,900. The system was aligned to each plate as well as calibrated to account for gravitational stage shift when collecting into low-binding 384-well plates (Eppendorf; catalogue number 0030129547). Single cells were sorted into every other well and the outer rows and columns were left empty. Visual confirmation of successful cutting was performed using the live imaging interface. To minimize air currents and maximize collection efficiency, the entire LMD system was operated in a sealed incubator environment. A protective shield plate was positioned above the sample stage to avoid collection errors. The collection plates were sealed, centrifuged at 1,000g for 2 min and frozen at −20 °C until further processing. Collection success was assessed post acquisition through data-driven quality control based on protein identification numbers, yielding an 82% effective collection rate (649 of 792 samples; see ‘Data filtering and quality control’).

Sample preparation and peptide loading

The following sample preparation steps were performed on an Agilent Bravo automated liquid handling platform in a semi-automated manner to minimize sample loss. Additionally, the plates were sealed with PCR sealing foil during incubation steps. Plates containing single cells were removed from −20 °C and immediately centrifuged at 2,000g for 2 min. The wells were washed with 28 μl of 100% ACN and subsequent dried in a vacuum concentrator at 45 °C for 20 min to ensure the presence of cut shapes at the bottom of the well. Then, 6 μl of lysis buffer (0.013% DDM in 60 mM TEAB buffer, pH 8.5) was added per well. Lysis was performed at 95 °C for 60 min in a PCR cycler (lid temperature 110 °C). We added 1 μl of 80% ACN and the samples were cooked at 75 °C for an additional 60 min. After a brief cooling, 1 μl of digestion mixture containing 4 ng μl−1 LysC and 6 ng μl−1 trypsin in 60 mM TEAB buffer was added and incubated overnight (approximately 18 h) at 37 °C. On the next day, the samples were immediately frozen at −20 °C until sample loading was performed.

The samples were loaded on C-18 tips (Evotip Pure, Evosep). The plates were thawed, immediately centrifuged at 2,000g for 2 min and kept on ice until loading. Evotips were activated in 1-propanol for 3 min. The tips were washed twice with 50 μl of buffer B (0.1% formic acid, 99.9% ACN) and centrifuged at 700g for 1 min between washes. A second activation in 1-propanol was performed for 3 min, followed by two washing steps with 50 μl of buffer A (0.1% formic acid). The disk was kept wet after the final wash. Then, 70 μl of buffer A was added per tip and the samples were loaded. Each well was rinsed with 10 μl of buffer A and added to the respective tip. For the peptide binding step, centrifugation was performed at 700g for 2 min. The tips were washed with 50 μl of buffer A. Finally, 150 μl of buffer A was added as overlay and the tips centrifuged at 700g for 15 s. The loaded tips were stored for maximum 3 days in an Evotip box containing fresh buffer A until loading on the LC-MS system.

LC–MS data acquisition

MS acquisition order was randomized across samples within each Evotip box. Analysis was performed on an Evosep One liquid chromatography system (Evosep) coupled to an Orbitrap Astral mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). An EASY-Spray source (Thermo Fisher Scientific) operating at 1,900 V connected the two systems. Peptide separation was achieved using a Whisper Zoom 80 SPD gradient on an Aurora Rapid C18 column (5 cm, 75-μm internal diameter, 1.7-μm particle size, IonOptics) at 60 °C. A throughput of 80 samples per day was achieved.

The Orbitrap Astral was equipped with a FAIMS Pro interface (−40-V compensation voltage, 3.5 l min−1 carrier gas, Thermo Fisher Scientific) and sample acquisition was exclusively performed in DIA mode. Orbitrap MS1 scans were recorded at a resolution of 240,000, a scan range from 380 to 980 m/z using 500% normalized AGC target and 100-ms maximum injection time. The window width of the Astral MS/MS scans was optimized in accordance to the sample’s precursor density. A total of 60 variable-width isolation windows were defined which covered the precursor selection range of 380 to 980 m/z (Supplementary Table 2). Fragment ion spectra were acquired with 20-ms maximum injection time, 500% normalized AGC target and 25% higher-energy collisional dissociation (HCD) collision energy.

Raw data processing

All 792 raw files were analysed in one single library-free search using DIA-NN (v.1.8.1)36. A human reference proteome FASTA file from UniProt (UP000005640, including reviewed entries, downloaded 22 March 2024) was provided. The search was performed with match-between-runs enabled and mass accuracy set to 8 and MS1 accuracy to 4 and the scan window radius to 6. Protein inference was based on genes using heuristic protein grouping. A maximum of one missed cleavage was allowed. The output ‘report.tsv’ file was normalized using directLFQ (v.0.2.19) at standard settings37. The resulting ‘report.tsv.protein_intensities.tsv’ file was used for downstream data analysis steps. No data imputation was applied.

Bioinformatics data analysis

Data collection and analysis were not performed blind to the conditions of the experiments. Non-parametric tests were used where applicable. For t-tests, data distribution was assumed to be normal but was not formally tested.

Data filtering and quality control

Initial data processing was performed using Python (v.3.12.5). At the sample level, measurements were excluded where the number of identified proteins was either 1.5 s.d. below or 3 s.d. above the median number of identifications across all samples. Quality control analyses, including assessment of protein group distributions and protein intensity rank plots, were performed on this filtered dataset to verify data quality and consistency. For subsequent analyses, an additional filtering criterion at the protein level was applied, requiring proteins to be detected in at least 70% of samples, if not stated otherwise. Where indicated for downstream analyses, data were standardized on the protein level using Z-score normalization within each patient. By this, protein intensities are centred around the mean and are scaled to unit variance on a per-patient basis.

Continuous analysis approach

To explore protein expression gradients along the zonation trajectories for each patient, an LMM was fitted, using the spatial score (S) as an independent variable, and protein expression (y) as the corresponding dependent outcome27. A random intercept effect on the patient the cell came from was added to control for differing expression baselines in different samples. Cells were removed by outlier intensity values using Tukey’s fences method38. The resulting expression intensities were normalized using a robust scaler (by which the median is removed and the interquartile range is divided). The full model is then given by following equation:

$${y}_{{ij}}={\beta }_{0}+{\beta }_{1}{S}_{{ij}}+{u}_{i}+{\epsilon }_{{ij}}$$

where yij is the response variable for cell j in patient i, β0 is the fixed intercept, β1 is the fixed slope, from here on called zonation coefficient, for the predictor variable Sij, ui is the random intercept for patient i, where \({u}_{i}\approx {{{\mathbb{N}}}}{\mathbb{(}}0,{\sigma }_{u}^{2})\), and εij is the residual error term, where \({\epsilon }_{{ij}}\approx {{{\mathbb{N}}}}{\mathbb{(}}0,{\sigma }_{u}^{2})\).

Once fitted, these models can be used to explore significant spatial expression gradients, by testing the zonation coefficient β1 against the null hypothesis that it equals zero (expression is spatially uniform in the central–portal axis) via a Wald test. The estimated zonation coefficients are compared with their standard error to determine the likelihood that the observed effect could occur by chance. A protein expression gradient that increases from portal to central vein is indicated by a zonation coefficient significantly lower than zero. In contrast, an expression gradient that increases towards the portal vein is indicated by a significant positive zonation coefficient. The strength of the gradient is determined by the absolute value of the zonation coefficients (β1). Proteins with a zonation coefficient greater than 1 ((∣β1∣ > 1) and a Q value less than 0.05 were considered significantly zonated.

To evaluate whether protein zonation gradients differ between experimental conditions, the zonation coefficients (β1) of the LMMs fitted for controls were compared with those of individuals with desmoplastic liver tissue. Only proteins with significant zonation gradients in the control condition were selected, and their zonation coefficients were compared using a Wald test. The null hypothesis that the difference in zonation coefficients (Δβ1) between the two conditions is zero is assessed by the Wald test. A test statistic that is distributed normally under the null hypothesis is obtained by dividing the observed difference by its standard error.

Statistical analysis and data visualization

PCA was performed using scikit-learn after data standardization using StandardScaler, by which each feature is centred and scaled to unit variance. Before PCA, outliers were removed using a Z-score-based approach, where samples with any feature having an absolute Z-score greater than 3 were excluded from further analysis. Explained variance ratios were calculated for each component. Cell type contamination analysis was performed to quantitatively validate hepatocyte purity using a cell-type-resolved liver proteome dataset from ref. 25. Cell-type-specific proteins were defined as proteins with intensity higher than 1 × 108 and at least fivefold higher than in any other cell type. The top 20 proteins with highest intensity were selected from each cell-type-specific protein set, compiling marker lists for human hepatocytes, hepatic stellate cells, Kupffer cells and liver endothelial cells. For each individual isolated cell, median ranks were calculated for each cell-type-specific marker protein set to assess potential contamination, with undetected proteins assigned the lowest rank of zero. For spatial analysis, both continuous and discrete approaches were employed. The continuous analysis is explained in detailed below. For discrete analysis, data were divided into 20 equidistant bins along the porto–central axis, and mean protein expression was calculated for each bin. Z-scores were calculated using scipy.stats.zscore function along the bin axis, with NaN values omitted from the calculation. LOWESS smoothing (fraction = 0.4) was applied to protein intensities plotted against the porto–central ratio of selected proteins to visualize their spatial behaviour. Moreover, protein expression heatmaps were used for visualization and proteins were ordered by the absolute expression difference along the spatial trajectory. Hierarchical clustering was performed using Ward’s method with Euclidean distance to identify general protein expression patterns. Overrepresentation analysis was performed using Enrichr’s web interface with the complete dataset as background. GSEA was performed using MSigDB collections (KEGG Pathways and MSigDB Hallmark) with proteins ranked by zonation coefficients from the LMM. Statistical significance was assessed using Benjamini–Hochberg correction for multiple testing. For visualization of entire pathways, the median Z-scores of the proteins assigned to the respective pathway were calculated. For comparison between analysis approaches on the protein level, protein intensities were analysed using both continuous (LMM-based) and discrete methods. For the discrete analysis, protein intensities were tested for spatial differences using one-way ANOVA implemented through ordinary least squares regression with statsmodels. Expression differences between the 20 spatial bins were tested using Type II sum of squares. P values were adjusted for multiple testing using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate. The statistical significance (−log10(Q value)) from both approaches was compared, and correlation between methods was assessed using Spearman correlation. A significance threshold of Q < 0.05 was applied for both methods. Moreover, kernel density estimation with 20 density levels was used to visualize the distribution of significance values. The comparison on the pathway level was conducted using both 3-bin and 20-bin approaches. GSEA was performed analogue as described above with proteins ranked by F-statistics from the respective ANOVA analyses. Statistical comparisons between conditions were performed using two-sided Wilcoxon tests for paired samples and two-sided unpaired rank sum tests for absolute differences. Delta values for zonation coefficient changes were calculated as the median absolute difference between conditions. Regression analyses included 95% confidence interval calculations for trajectory visualization. First and third quartiles are shown by box plots with centre line indicating median and whiskers extending to 1.5× interquartile range. All visualizations were generated using seaborn and matplotlib libraries in Python.

Transcriptomic–proteomic correlation

We used the MERFISH spatial transcriptomics dataset from ref. 11 to identify landmark genes that are highly expressed in either pericentral or periportal hepatocytes. We defined landmark genes as those expressed in at least 70% of cells in a given region (central or portal) and showing a differential expression score of at least 30 between the two zones. The selected landmark genes were then used to computationally infer zonation39. Using this landmark-based approach, we next computed zonation scores on a single-nucleus RNA sequencing dataset from healthy human hepatocytes40. Once zonation scores were established for each cell, we applied a linear mixed-effects model to calculate zonation coefficients, mirroring the approach used for our proteomics data. To ensure consistency with the proteomics normalization and noise reduction, we included only RNA with a median expression greater than zero across healthy hepatocytes. Finally, we compared the RNA zonation coefficients with their matched proteins (n = 419 RNA–protein pairs).

Cross-species comparison analysis

Cross-species conservation of protein zonation was assessed by comparison of human liver data with the publicly available mouse scDVP dataset17. Protein homology mapping between human and mouse was performed using DIOPT (DRSC Integrative Ortholog Prediction Tool), by which multiple orthology prediction algorithms are integrated to provide comprehensive homology scores41. The protein filtering and normalization strategies described in the original paper were maintained. The mouse data were then re-analysed using our continuous analysis approach to enable direct comparison of zonation patterns between species.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

First Appeared on

Source link