Beneath the Antarctic Ice, Scientists Discover 300 Gigantic Canyons with Major Effects on Climate Circulation

The seafloor beneath Antarctica’s ice has long existed in climate models as a blank space, a featureless plane where deep ocean simply stops at the continental margin. That cartographic convenience has now collapsed. A systematic mapping effort completed last year has revealed that the ocean floor surrounding Antarctica is scored by hundreds of deep submarine canyons, some plunging more than four kilometers, arranged in patterns that differ fundamentally between the continent’s eastern and western halves.

What researchers found challenges a central assumption underlying many predictions of sea level rise. The canyons function as conduits, and the direction of flow through them matters enormously. Warm water moving landward through these channels can undercut ice shelves from below, accelerating melt in ways that smooth seafloor models cannot capture. Water moving seaward carries fresh meltwater into global circulation, altering salinity gradients that drive ocean currents.

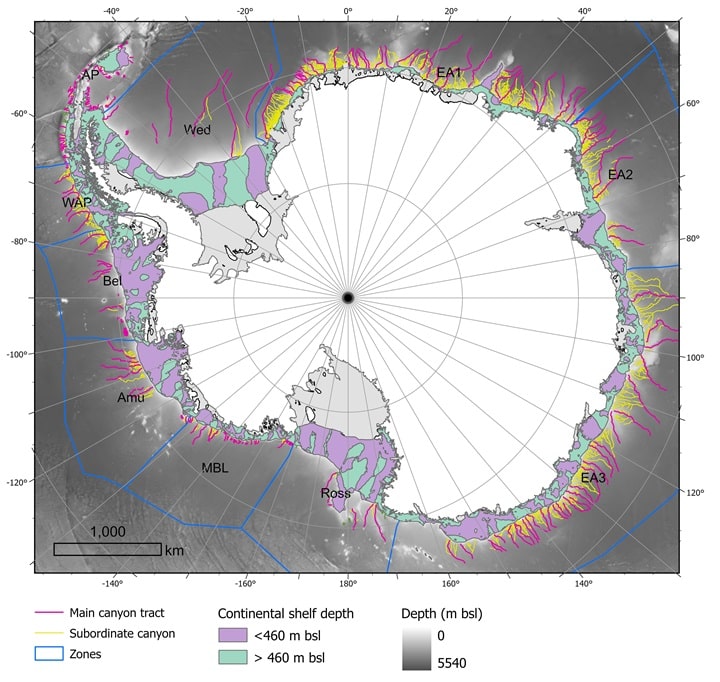

The catalogue, published in Marine Geology, identifies 332 submarine canyons along the Antarctic margin, a fivefold increase over previously documented features. Researchers from the University of Barcelona and University College Cork compiled the dataset using high resolution bathymetric measurements collected during more than 40 international research expeditions. The surveys deployed multibeam sonar systems capable of mapping seafloor topography through ice covered waters and into regions previously inaccessible to surface vessels.

Some of the newly documented canyons reach depths exceeding 4,000 meters, dimensions that place them among the largest submarine canyon systems on the planet. Their distribution is not uniform. The mapping reveals a sharp contrast between eastern and western sectors that reflects different geological histories and, potentially, different vulnerabilities to ongoing climate change.

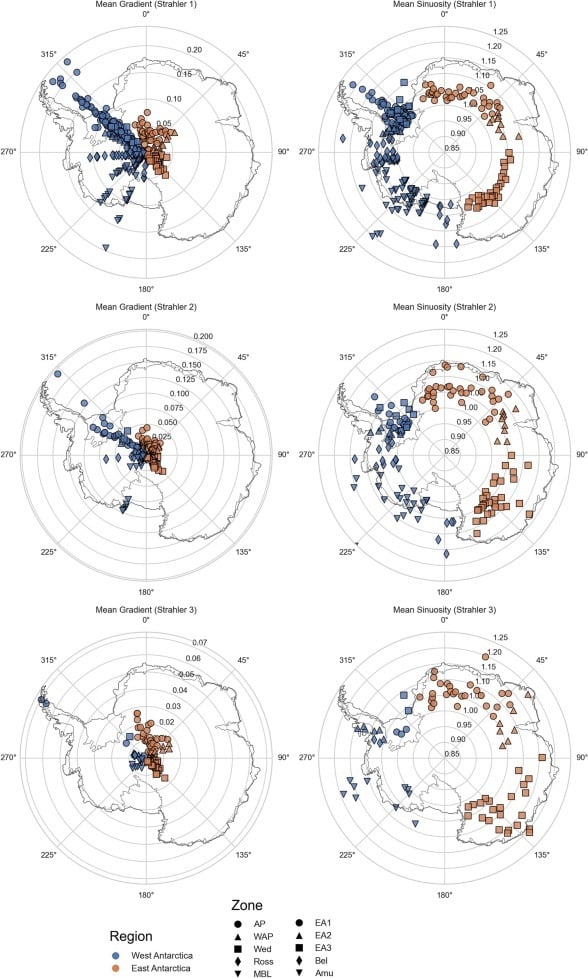

Eastern Antarctic canyons exhibit branched configurations with multiple tributary channels feeding into main axes, indicating prolonged development beneath stable ice sheets. Western Antarctic systems are steeper, straighter, and shorter, morphologies consistent with more recent formation under dynamic glacial conditions. The structural differences align with observational data showing West Antarctic ice experiencing more rapid change than its eastern counterpart.

The topographic features identified in the survey play direct roles in regulating exchanges between the Antarctic continental shelf and the deep Southern Ocean. Dense saline water formed during sea ice production drains from the shelf through these channels, contributing to the global thermohaline circulation that distributes heat and nutrients across ocean basins. Simultaneously, warm circumpolar deep water can access ice shelf cavities through the same canyon axes, delivering heat that accelerates basal melting.

Dr. Alan Condron from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution described this bidirectional transport as central to understanding how heat reaches Antarctic ice and how freshwater from melting escapes into the global ocean. His comments accompanied the study’s publication, emphasizing that canyon driven exchange is not a marginal process but a fundamental mechanism in ice ocean interactions.

The structural contrasts between eastern and western systems carry implications for regional vulnerability. Western Antarctic canyons, steeper and more direct, may provide more efficient pathways for warm water to reach ice shelf grounding lines. Eastern systems, with their branched configurations, might moderate or delay such incursions. Direct measurements of water transport through individual canyons remain limited, and distinguishing between actively flowing systems and relict features will require targeted oceanographic campaigns.

The mapping effort encountered significant operational constraints. Bathymetric data collection in Antarctic waters requires navigating hazardous sea ice conditions, and extensive areas beneath permanent ice shelves remain inaccessible to surface vessels. Researchers noted that some canyon systems may extend further landward than currently documented, their full extent concealed beneath floating ice.

The survey provides morphological snapshots rather than direct measurements of water transport. Quantifying actual flow rates and heat fluxes through specific canyon axes will require instrument moorings deployed across multiple seasons. Several such deployments are currently planned as part of international Antarctic research programs, but comprehensive coverage remains years away.

The study also cannot determine whether individual canyons are actively transporting water and sediment under present climatic conditions or represent relict features from earlier glacial periods. Resolving this uncertainty will require integration with circulation models and direct observations of near bottom water movement, data that do not yet exist for most of the mapped systems.

The revised canyon inventory addresses a recognized limitation in climate simulation capabilities. Most Earth system models have historically represented the Antarctic seafloor as relatively featureless, averaging out topographic variations that can concentrate or deflect water movements. The new morphological data enables modelers to incorporate realistic bathymetry into simulations of ice sheet behavior and ocean circulation.

Incorporating canyon scale topography affects modeled outcomes in several ways. Simulations that include these features show enhanced transport of warm water toward ice shelf grounding lines, accelerating projected melt rates in West Antarctic basins. They also indicate more efficient export of meltwater from ice shelf cavities, altering predictions of how freshwater plumes distribute and affect sea ice formation.

The research team emphasized that this mapping represents a foundational dataset rather than a final answer. Future work will focus on integrating these morphological observations with oceanographic measurements and ice penetrating radar surveys to trace canyon systems beneath the ice sheet margin.

International collaboration will be essential, as no single nation maintains the logistical capacity to survey the entire Antarctic coastline at required resolution. The seafloor beneath Antarctica’s margin bears little resemblance to the simplified representations long used in climate science.

First Appeared on

Source link