Scientists Have Cracked the Mystery of Snake Pee

The science of poop has yielded some fascinating results, but the latest installment in this beat may be the most astounding yet. After decades of noticing but generally not understanding why reptiles “pee” crystals, researchers finally believe they have the answer.

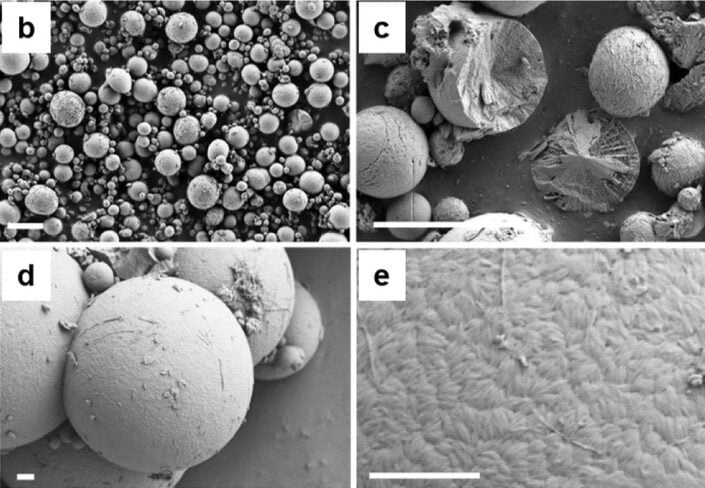

In a Journal of the American Chemical Society paper published today, a team of organic chemists and herpetologists describes their investigation of pee crystals from more than 20 reptile species. Simply, reptiles package up excess nitrogen into tiny, textured spheres consisting of even smaller microcrystals. These microscopic processes offer an evolutionary advantage for snakes, in addition to hinting at some broader implications for human health, according to the researchers.

The science of urine

The project began with an odd inquiry that Jennifer Swift, a crystallographer at Georgetown University, received from herpetologist Gordon Schuett. Specifically, Schuett wanted to know why, despite feeding the reptiles under his care the same food and water, there was such a weird variety in their pee crystals.

“What he observed was that among all of the critters that he had in his museum, some of them would excrete urates that dry to a rock-hard mass, and some of them would dry to something that looked like dust,” Swift, the study’s senior author, told Gizmodo in a phone call. “He asked if I knew what was going on, and I said, ‘I have no idea. Why don’t you send me some samples?’”

Swift’s focus thus far had been the accumulation of uric acid crystals in humans, which leads to serious health issues such as gout or kidney stones. Uric acid is one of three main forms produced by animals while breaking down excess nitrogen in their bodies. We mammals pass excess nitrogen as urea, which, along with lots of water, becomes urine.

On the other hand, reptiles and avians (both descended from dinosaurs) excrete nitrogen as solid uric acid, which researchers believe could have allowed the animals to preserve water in dry climates.

Cracking the mystery of “pee” crystals

Given the pesky implications of solid uric acid in humans, researchers did clock the potential benefits in learning how reptiles appeared to pass these crystals without too much trouble. But the few attempts to properly describe the molecular mechanisms in play weren’t very successful, according to Swift.

“Because we didn’t know what we were dealing with, either, we cobbled together literally every analytical method we could under the Sun, and studied it in every direction that we could,” she said.

This included X-ray diffraction studies and high-resolution microscopy analysis of urates, or solid uric acid, from around 20 different reptile species, primarily snakes.

Their findings revealed the reptiles’ remarkably complex mechanism for passing nitrogen. First, they produce tiny spheres of uric acid nanocrystals. Some species directly dispose of these microspheres, whereas others were “recycling” the crystals to react with liquid ammonia, a deadly neurotoxin.

This enables the snakes to transform ammonia into something solid—particles that are much less toxic that, once excreted, would be “dust that would blow away in the wind,” Swift explained. What this potentially means is that uric acid could play a protective role for the snakes.

Of course, it’s still quite a leap to suggest that the same could apply for humans, Swift admitted. Still, it suggests that there’s more to be learned about the role of uric acid in biology, she said, adding, “Too much is a problem. Eliminating it completely is not an option.”

Either way, the new findings demonstrate the “value in taking biomimetic approaches to complex problems,” Swift added. “Millions of years of evolutionary history have allowed things to thrive in ways that we might not normally think of. Nature has a lot of remarkable processes that we just don’t understand, because we haven’t taken the time to look at them.”

First Appeared on

Source link