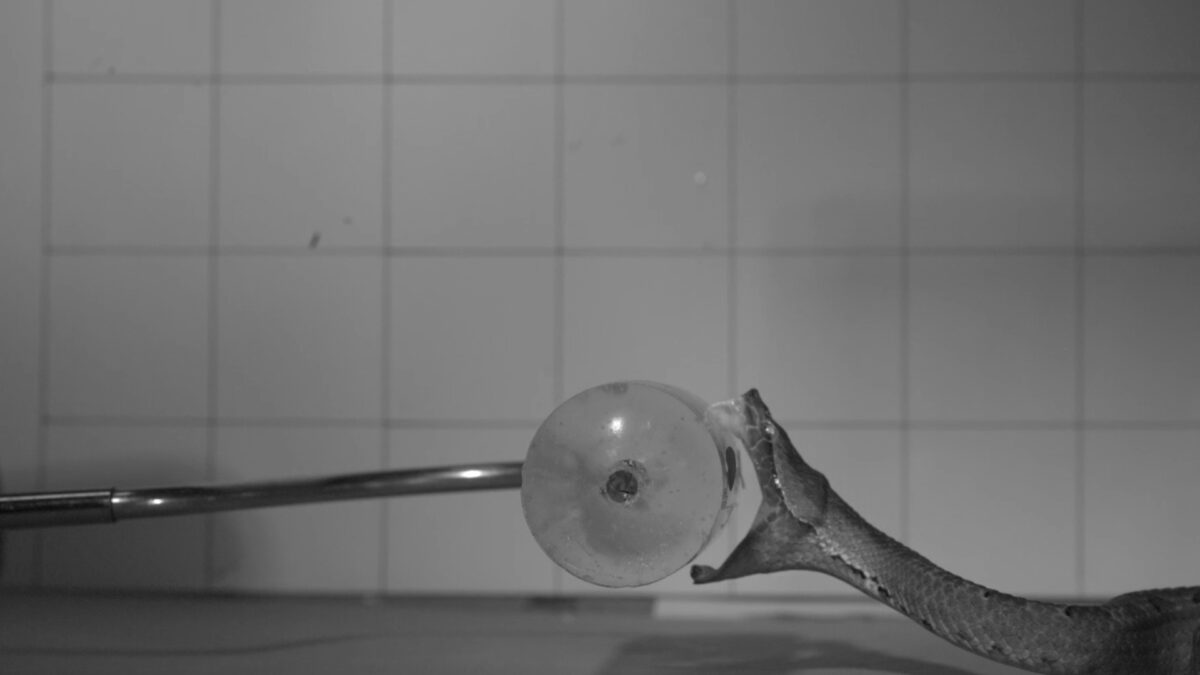

This Is What a Venomous Snake Bite Looks Like at 1,000 Frames per Second

If you’ve ever been morbidly curious about what it would look like to have a snake sink its deadly venomous fangs in you, you’re in luck. In new research out today, scientists have captured high-speed footage of snakes just as they’re about to go in for the kill.

Researchers in Australia and France meticulously (and safely) recorded dozens of species across the three families of venomous snakes mid-bite. They found that these snakes have important differences in how they attack their victims and deliver venom. The findings represent the most extensive documentation of venomous snake bites collected yet, the researchers say, and offer insight into the different ways these slithery reptiles have evolved to hunt their prey.

“This gives us a first opportunity to directly compare these three families of venomous snakes,” lead author Alistair Evans, a scientist studying the evolution of biomechanics at Monash University, told Gizmodo.

How to safely watch a snake bite

Evans has long studied how animals feed, particularly in their use of teeth. One of his newer PhD students, Silke Cleuren, was especially interested in snake bites. Recent advances in video technology have also now made it possible to capture the mechanisms of a snake strike and bite in better detail than ever.

But while Australia has its fair share of native venomous snakes, staying close to home would have limited just how many the scientists could have recorded under a controlled setting. Instead, they collaborated with scientists in France who had an existing partnership with Venomworld, a venom production facility in the country. This allowed them to closely study, for the first time, species from all three major families of venomous snakes: viper, elapid, and colubrid snakes.

All told, they recorded 36 species and more than 100 bites. For the extra squeamish, don’t worry: the snakes only bit a piece of ballistics gel wrapped around a cylinder intended to mimic prey.

“The main advantages of our study is that we examined the full strike behavior in the largest number of species while they were in the same conditions, and we videoed them at high speed (1,000 frames per second) and reconstructed their movement in 3D,” Evans said. “All previous studies had been with only a limited number of species—usually fewer than 10.”

No two snakes are the same

The team found all sorts of differences between the various snake families.

Vipers, which are primarily ambush predators, were overall the fastest biters; for instance, their fangs reached their prey within 100 milliseconds after making a strike, and they moved the fastest when about to attack their prey. They also tended to be more selective, in that they would only close their jaws and send the venom coursing into their prey once the fangs were tightly secured. If their first bite didn’t land just right, the snakes would remove their fangs and bite again.

“Snakes that feed on mammals also were faster—in fact, some snakes were faster than the mammalian startle response, basically meaning that the snakes have bitten their prey before they can move, in the blink of an eye (at least for humans),” Evans said.

Elapid snakes (which include cobras) were sneakier in approaching their would-be dinner, and they tended to bite their victims repeatedly to deliver their deadly venom. Colubrid snakes have their fangs in the rear of the mouth, meaning their bites have to firmly clench around their prey. They also usually swept their jaws from side to side following a bite, creating crescent-like gashes in their prey for their venom to seep into.

The findings, published Thursday in the Journal of Experimental Biology, provide another important “piece of the puzzle of how snakes have adapted to their various lifestyles and prey,” Evans said.

Though his team isn’t planning to follow up on this specific project, he notes there are plenty more for other researchers to explore. They mostly studied vipers, for example, meaning future similar studies could include a greater selection of elapid and colubrid snakes. “It would be very interesting to see more about how snakes vary their approach to prey of different sizes and in different environments,” he added.

Personally, I’m just glad my nightmares will now have more real-life material to draw from.

First Appeared on

Source link