This New Artificial Muscle Could Let Humanoid Robots Lift 4,000 Times Their Own Weight

Imagine a rubber band that turns into a steel cable on command. Now imagine it’s inside a robot.

That’s the basic trick of a new artificial muscle built by researchers at the Ulsan National Institute of Science and Technology (UNIST) in South Korea. In a study published in Advanced Functional Materials, they describe a soft, magnetically controlled muscle that can flip between floppy and rock-solid — and deliver more energy than human muscle tissue ever could.

In its stiffened state, this tiny strip of material weighs about 1.2 grams yet can hold up to 5 kilograms. That’s roughly 4,000 times its own weight. When softened, it can stretch to around 12 times its original length and contract with a strain of 86.4%, more than twice that of typical human muscle.

The muscle’s work density — how much mechanical energy it can deliver per unit volume — reaches 1,150 kilojoules per cubic meter. That’s about 30 times higher than human muscle tissue. For soft robotics, that’s like jumping from a scooter to a sports bike overnight.

Why Are Robot Muscles So Hard to Build?

If you’ve ever seen videos of soft robots — things like squishy tentacles, inflatable grippers, silicone worms — you’ve probably noticed a pattern. They’re great at bending and twisting. They’re less great at, say, lifting something heavy without collapsing.

That’s because most artificial muscles face an annoying trade-off. They can be very stretchable or very strong, but rarely both at the same time. Soft materials like gels and elastomers can deform dramatically but don’t generate much force. Stiffer materials can pull hard but only over small distances. When engineers try to push both levers at once — big strain and big force — the material usually tears, stalls, or tires out.

Researchers measure this compromise with work density. Many soft artificial muscles hit respectable strain values, between 40 and 60 percent, but only modest work densities. Hydrogels, shape-memory polymers, liquid crystal elastomers, and twisted fibers all occupy different corners of this map. Each technology has its own charm, but none quite behaves like biological muscle, which can stretch, contract, and carry weight repeatedly without falling apart.

On top of that, stiffness matters. A useful artificial muscle should be able to go limp when it needs to move and lock up when it needs to hold — think of how your arm can relax or brace. Most artificial muscles don’t do that. They stay either squishy or rigid all the time.

This is the background problem the UNIST team walked into: how do you build a muscle that can be soft and strong, stretchy and powerful — and controlled from the outside?

A Muscle Made of Plastic, Magnets, and Memory

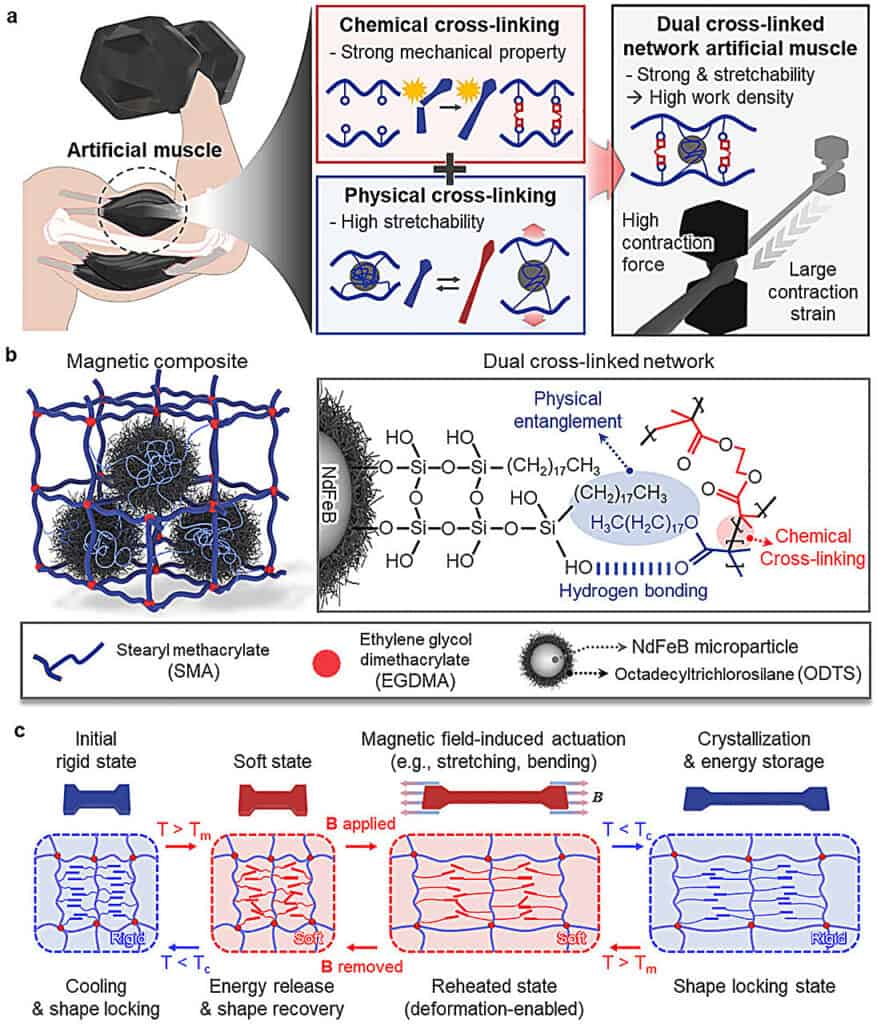

The UNIST group’s answer is a magnetic shape-memory polymer with a dual personality at the molecular level. At its heart is a plastic called a shape-memory polymer. These materials can be “programmed” into a temporary shape, then return to their original form when heated. In this case, the base polymer is stearyl methacrylate, cross-linked with a small amount of another molecule, ethylene glycol dimethacrylate.

The researchers built two overlapping networks into this polymer. One is a chemical network of permanent covalent bonds. The other is a physical network of long side chains that can crystallize and melt. When the side chains crystallize, the material becomes stiff and glassy. When they melt, it softens into a stretchy, rubbery state.

This dual cross-linking design lets the muscle switch stiffness on demand. In lab tests, its stiffness jumps from about 213 kilopascals — soft, like rubber — to 292 megapascals, hundreds of times stiffer, closer to hard plastic. That’s a change of more than a thousand-fold.

Then the team added the superpower: magnets. They embedded tiny neodymium-iron-boron microparticles throughout the polymer. Before putting them into the plastic, they coated the particles with a thin silica shell and a layer of octadecyltrichlorosilane — an organosilicon mouthful that basically makes their surfaces friendly to the polymer. That surface treatment helps the particles disperse evenly and hook into the physical network instead of clumping.

Once the composite is cured, it looks like a simple, flexible strip. But it’s both thermally responsive — it stiffens and softens with temperature — and magnetically active, reacting to external magnetic fields. The muscle can be “magnetized” in a specific curled or bent shape by exposing it to a strong magnetic field while it’s soft then cooling it to lock in that configuration. Inside, the microparticles line up, giving the strip a built-in magnetic direction, a kind of muscle memory based on magnetism.

So, when the material is reheated above its transition temperature, it softens and can move under a magnetic field: bend, twist, or stretch, depending on how the field is applied. When it cools, it locks into place again.

That’s where the numbers get wild. In controlled tests, the material reached elongation at break of 1,274 percent. This means it extended to more than twelve times its length before tearing. It also showed an actuation strain of 86.4 percent under working conditions, more than double that of human muscle. And its work density hit 1,150 kilojoules per cubic meter at an optimal cross-linking density.

In its stiff state, a strip weighing about 1.25 grams could support a 5-kilogram load without failing. In the soft state, it still held one kilogram — more than 800 times its own weight — while being able to move and stretch.

As Professor Hoon Eui Jeong put it in the UNIST press release, “This research overcomes the fundamental limitation where traditional artificial muscles are either highly stretchable but weak or strong but stiff. Our composite material can do both, opening the door to more versatile soft robots, wearable devices, and intuitive human-machine interfaces.”

What These Muscles Can Actually Do

It’s one thing to break records on a stress–strain curve. It’s another to act like something we’d recognize as a muscle. So, the team staged a few robotic demos.

In one experiment, they shaped a strip into a kind of robotic arm and hand. They magnetized it in a curled configuration so that, under a magnetic field, the hand could close around a bar. After softening the material with an infrared laser, they used magnets to make the hand grip. Cooling it down locked that grip in place. Then they reheated the arm segment only. The polymer remembered its original length and contracted, lifting a 115-gram weight with about 39 percent strain recovery. To extend again, they could either let the suspended weight pull it back out or reapply a magnetic field.

In another test, they pre-stretched two muscles to more than double their length and used them like parallel arms to lift 77-gram loads on each side. When heated, the muscles contracted and pulled the weights up, recovering about half of their pre-strain.

These are proof-of-concept experiments, not finished commercial devices. But they showcase an unusual combination of features in one material. This material can be reprogrammed magnetically into new shapes without refabrication. It can toggle stiffness by changing temperature. It can lift heavy loads relative to its weight. And it can deliver large, reversible strains over many cycles.

In the broader landscape of artificial muscles, that’s rare. Many systems that rely on pneumatic pressure or electric fields need bulky support hardware like pumps, compressors, or high-voltage power supplies. Others, like carbon nanotube yarns and twisted fibers, excel at one metric, such as speed, power, or strain, but don’t combine them all. Here, the hardware is mostly just a strip of smart plastic with magnets inside.

From Sci-fi Exosuits to Surgical Tentacles

So, what could you actually do with a muscle like this? Well, picture exosuits that feel like clothing rather than armor, surgical tools that bend delicately around organs, home robots that won’t crush your fingers when they grab stuff around you.

This new material aims squarely at that future. Because it can go soft when it moves and stiff when it holds, it’s a good fit for wearable assistive devices, humanoid robots, and medical tools. Imagine a glove that helps a person lift their arm but relaxes when they rest, or a bendable catheter that stiffens in place, then relaxes for removal. It could even make adaptive grips and interfaces that conform to fragile objects, then lock in place to carry them.

It also taps into a larger trend in robotics, moving away from rigid, industrial machines and toward soft, compliant systems that can safely operate around people, in homes, hospitals, and unpredictable environments.

There are, of course, caveats. The current system still relies on thermal control, which means you have to heat and cool the material to switch states. That can limit speed and energy efficiency, especially outside a lab water bath. Future versions might use more efficient heating methods or tailor the polymer chemistry to shift at more convenient temperatures. Magnetic actuation also has range and scaling challenges. Very small devices work well with magnets, but driving large systems may require stronger fields or clever designs.

And then there’s real-world durability. While the material held up well over hundreds of lab cycles, long-term use in a robotic glove or implanted device would demand thousands or millions of cycles, exposure to sweat or bodily fluids, and constant mechanical abuse.

Still, the basic physics of what the team demonstrated — a soft muscle that can behave like rubber one second and structural plastic the next, while out-lifting human tissue by an order of magnitude or more — is a signpost. Artificial muscles have always lived at the edge of science fiction. We imagine powered suits, synthetic limbs, squishy robots rebuilding disaster zones, tiny machines roaming inside the body. Most of those visions run into the same hurdle: you need something that moves like flesh but works like a machine.

This new UNIST muscle doesn’t solve everything. But it pushes that frontier forward in a very concrete way. Instead of choosing between softness and strength, it simply asks: why not both?

The findings appeared in the journal Advanced Functional Materials.

First Appeared on

Source link