Strain displacement in microbiomes via ecological competition

Ecological theory predicts conditions for strain invasion and displacement

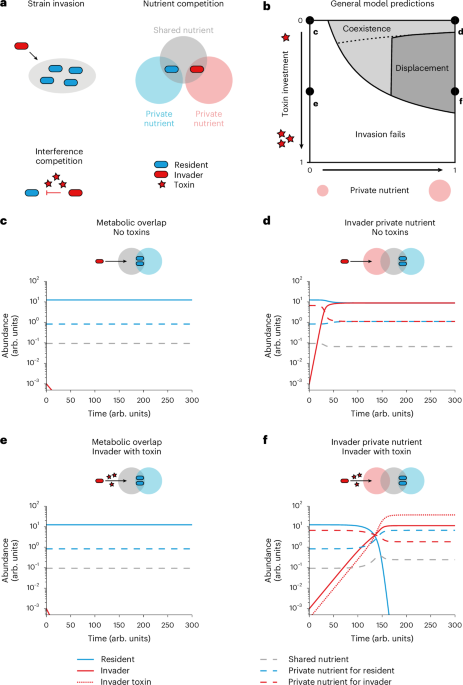

We are interested in what enables a microbial strain to invade an established community and out-compete an existing strain. Mathematical models, particularly from theoretical ecology, have proved to be a powerful way to cut through the complexity of microbial communities and identify general predictions10,14,23,25,26,27. We begin, therefore, by building a general mathematical framework based upon previous theoretical work of resource competition in microorganisms and plants23,28,29 (Supplementary Information). Following the biology of microbial communities such as the human gut microbiome, the models capture two key forms of ecological competition. Firstly, we assume that the newly arriving strain will experience competition for resources30,31, where its growth rate upon arrival depends upon the level of the nutrients needed for growth15,17,32,33. Secondly, we include the possibility that our focal strain may engage in interference competition, which can be either via the release of toxins into the environment or via a contact-dependent mechanism such as the type six secretion system18,34.

Although the impacts of nutrient and interference competition on microbial ecology have been widely studied11,14,17,34,35,36,37,38, how they act in combination has not. By combining all three key elements in our modelling—ecological invasion, nutrient competition and interference competition—we can investigate what is required for a strain to invade and out-compete a resident strain in a microbial community (Fig. 1a). We first consider a general consumer-resource model

$$\begin{array}{c}\frac{d{N}_{\sigma }}{dt}={N}_{\sigma }({\lambda }_{\sigma }({\bf{N}},{\bf{x}})-{\delta }_{\sigma })\\ \frac{d{x}_{i}}{dt}={g}_{i}({\bf{N}},{\bf{x}})-{\sum }_{\sigma }{N}_{\sigma }{d}_{i\sigma }({\bf{N}},{\bf{x}}),\end{array}$$

(1)

where Nσ is the abundance of strain σ; xi is the abundance of nutrient or toxin i; λσ(N, x) is the per capita growth rate of strain σ; δσ is the dilution rate of strain σ; gi(N, x) is the net nutrient influx rate or toxin production rate, meaning the rate at which chemical species are introduced into the system; and diσ(N, x) is the uptake rate of nutrient or toxin i by strain σ. This general consumer-resource model captures nutrient competition by a positive dependence of growth rate λσ on limited, shared nutrients xi, while interference competition is captured by a negative dependence of growth rate λσ on diffusible toxins xj or competitors Nσ′ that carry contact-dependent weapons. The model reveals important differences between the two forms of ecological competition when a strain invades. Specifically, we show (Theorem 1, Supplementary Information) that a rare invading strain τ can invade a community of strains with equilibrium abundances N1, …, Nτ−1 and nutrient or toxin abundances x1, …, xI precisely when its initial growth rate overcomes its dilution, that is

$${\lambda }_{\tau }\left({N}_{1},\ldots ,{N}_{\tau -1},{N}_{\tau }=0,\,{x}_{1},\ldots ,{x}_{I}\right) > {\delta }_{\tau }.$$

(2)

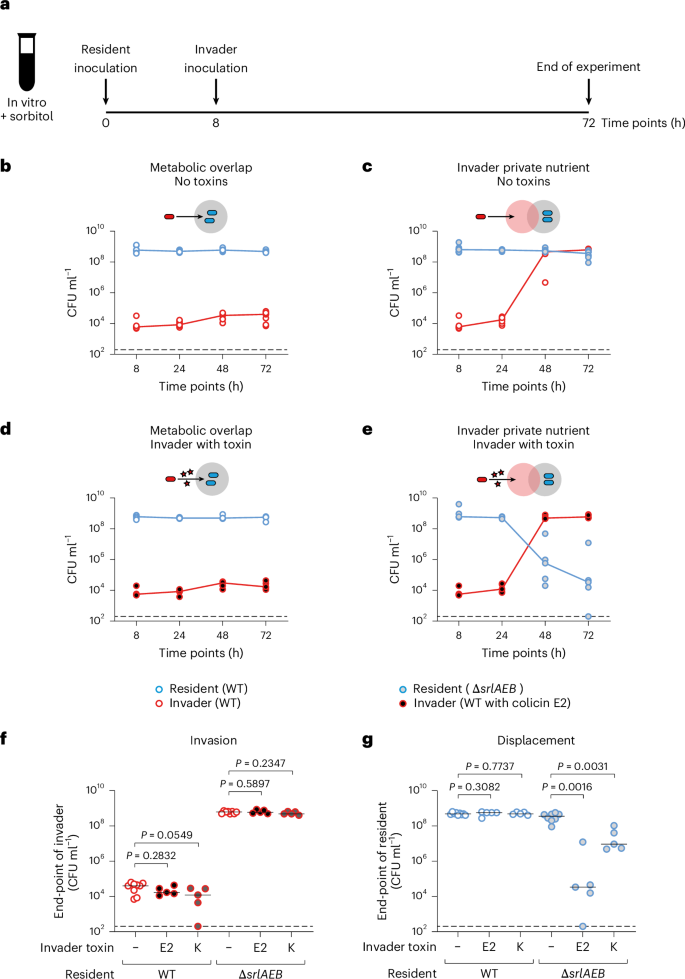

a, Our theory captures three key aspects of the natural ecology of bacterial competition: ecological strain invasions in which an invader (red) invades the niche of a resident (blue), nutrient competition over a shared nutrient (grey) and interference competition (red stars for toxins produced by the invader). b, Invasion success is the result of varying toxin investment (z) or the supplementation of a private nutrient for an invader (mI). Invasion fails (white region) if private nutrients are not sufficiently available. If an invader has sufficient access to a private nutrient, it can coexist with a resident strain (light grey region), but if it invests sufficiently into a toxin, it can displace the resident strain (dark grey region). The invasion boundary is analytically determined (Supplementary Equation (12), Supplementary Text), and the displacement boundary is plotted numerically (Methods), with the dashed line delimiting the analytically derived bound for the displacement boundary (Supplementary Equation (17), Supplementary Text). c–f, Numerical solutions of points in b in which the invader has not invested in the production of a toxin and has no private nutrient (c; mI = 0, z = 0), has not invested in the production of a toxin but has an abundant private nutrient (d; mI = 1, z = 0), has invested in a toxin but has no private nutrient (e; mI = 0, z = 0.5) and has both invested in a toxin and has an abundant private nutrient (f; mI = 1, z = 0.5). Solid lines indicate the abundance of strains (resident in blue, invader in red), the red dotted line indicates the abundance of the invader toxin and the dashed lines indicate the abundance of nutrients (shared nutrient in grey, private nutrient for the resident in blue, private nutrient for the invader in red). Parameter values used for simulating the invasion dynamics from equation (3) (Methods): \(m={m}_{{\rm{R}}}=1,\delta =D=d=0.15,\,{R}_{{\rm{R}}}=\)\({r}_{{\rm{R}}}={R}_{{\rm{I}}}={r}_{{\rm{I}}}=1,{C}_{{\rm{R}}}={c}_{{\rm{R}}}={C}_{{\rm{I}}}={c}_{{\rm{I}}}=1,\,s=1,\,\)\({k}_{{\rm{R}}}={k}_{{\rm{I}}}=1,\,{K}_{{\rm{R}}}={K}_{{\rm{I}}}=K=10,\,g=1,\,p=0.7\).

Therefore, as weapons of the invading strain do not directly increase its own initial growth rate λτ but rather decrease the growth rates λσ of other susceptible strains σ, a rare invader strain that is equipped with a weapon cannot invade the community unless it can invade without it (Theorem 1, Supplementary Information). Put another way, the conditions for invasion are independent of whether the focal strain is using interference competition—whether it is a contact-dependent system or diffusing an antimicrobial toxin. This result is true for both well-mixed conditions (Theorem 1) and spatially structured environments (Theorem 2, Supplementary Information). The prediction arises because the benefits of interference competition scale with population size, such that when a strain is sufficiently rare, their impacts on other strains are vanishingly small, and instead, the user merely suffers from the cost associated with production of bacterial weapons. Instead, the model predicts that invasion is determined by the ability to compete for nutrients sufficiently well to achieve a sufficient initial growth rate λτ. In the model, this condition occurs when there is enough of a nutrient xi that the invading strain can use but that the resident microorganisms cannot, which we refer to here as a ‘private’ nutrient. Finally, if a strain is invading a community where resident strains are producing antimicrobial toxins, its growth rate also will have to be high enough to overcome any mortality cost from the antimicrobial. This result means that we can approximate the effects of a resident’s toxin using the growth rate of the invader at invasion, and we therefore do not explicitly study the effects of residents’ toxins further.

Next, to illustrate the general modelling predictions, we numerically simulate the ecological dynamics that occur after a strain invades (Fig. 1c–f and Extended Data Figs. 1 and 2). The main figures (Fig. 1c–f) show the dynamics of the continuous flow version of our model, which is the form that allowed steady-state calculations and the most analytical tractability (equations (1) and (2)). In the supplement (Extended Data Fig. 3), we show that the same predictions hold for a batch culture version of our model, which is the basis of our experimental work (below). For simplicity, our model captures the resident community as a single strain that has an overlapping ecological niche with the invader (Methods).

Consistent with our analytics, we see that the invasion of the focal strain depends upon its having a private nutrient, but invasion does not depend upon the use of an antimicrobial toxin (Fig. 1b–d). However, the toxin is critical for the outcome of competition over longer time periods. Specifically, in the absence of a toxin, strain invasion leads to coexistence of the two strains (Fig. 1e). By contrast, when the invader invests sufficiently into toxin production, strain invasion leads to the removal of the resident and strain displacement (Fig. 1b; compare panels d and f of Fig. 1). We further confirm that displacement occurs because of increased density of the invading strain as it grows on its private nutrient by showing that a sufficient initial density of invaders can cause displacement of a resident strain without a private nutrient for the invader (Extended Data Fig. 4). To explore Theorem 2 (Supplementary Information), we also performed spatially explicit simulations in which the resident strain is stable and spatially homogeneous, and the invader is seeded at low density along a spatial axis (Extended Data Fig. 5). As for well-mixed conditions, a rare invading strain can grow only if it has a private nutrient, and it is these conditions that empower it to displace a resident strain if it uses interference competition.

Strain displacement occurs as predicted with engineered E. coli strains

To test our modelling predictions, we turned to E. coli as a model organism. This species is both amenable to genetic manipulation and a good test case because competition among strains can be critical for human health: some E. coli strains are harmless members of the gut microbiome, while others cause deadly diseases whose treatment is hindered by the rising incidence of AMR24,39,40.

To manipulate the strength of nutrient competition between strains, we engineered a ∆srlAEB mutant of E. coli K12 that cannot grow on the sugar alcohol sorbitol. By then adding sorbitol in the media and using this E. coli ∆srlAEB as a resident strain, we can study the key scenario identified in the modelling in which an invading wild-type strain has a private nutrient (Fig. 2a). By contrast, if we make both the resident and the invading strain the wild type, we capture the condition of complete niche overlap. To manipulate interference competition between the two strains, we equipped the invader with colicin E2, a plasmid-borne DNAse colicin that is a potent antimicrobial protein and has been well characterized previously19,35,41,42. The colicin E2 plasmid is naturally carried by some E. coli strains and leads to both colicin production and immunity against intoxication via production of the cognate immunity protein from the same promoter. This plasmid is not transferrable without a helper plasmid, which is not present in our experiments.

a, Scheme of invasion experiments using isogenic E. coli strains. LB medium is supplemented with 4% sorbitol and then inoculated with either wild-type (WT) E. coli or an isogenic ∆srlAEB mutant that cannot use sorbitol. A WT E. coli with or without colicin E2 is inoculated 8 h later. Populations are enumerated using selective plating. b, Ecological invasion experiment using the scheme in a for scenarios modelled in Fig. 1c–f. Lines connect medians, and dashed black lines indicate the detection limits of selective plating. Here the invader does not have a private nutrient (resident is WT E. coli; kanamycin resistant; open blue circles) and does not have a toxin (invader is WT E. coli; chloramphenicol resistant; open red circles). N = 9 independent biological replicates, each from independent experiments. c, Invader has a private nutrient (resident is E. coli ∆srlAEB; kanamycin resistant; blue circles with grey fill) and does not have a toxin (invader is WT E. coli). N = 8 independent biological replicates each from independent experiments. d, Invader lacks a private nutrient (resident is WT E. coli) but has a toxin (invader is E. coli with colicin E2; chloramphenicol resistant; red circles with black fill). N = 5 independent biological replicates each from independent experiments. e, Invader has both a private nutrient (resident is E. coli ∆srlAEB) and a toxin (invader is E. coli with colicin E2). N = 5 independent biological replicates each from independent experiments. f,g, Same experiment as in b–e, but only the end-point values at 72 h are plotted for both the invader (f) and the resident (g). See descriptions above for sample size. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare population sizes when the invader does not use a toxin with when the invader uses either colicin E2 or colicin K. Population dynamics of ecological invasion experiments using colicin K are shown in Extended Data Fig. 6i,j (N = 5 independent biological replicates each from independent experiments for experiments with colicin K). Black lines indicate medians; dashed lines indicate the detection limits of selective plating.

With these tools in place, we then tested the predictions of our mathematical model with invasion assays in lysogeny broth (LB) supplemented with sorbitol (Fig. 2a). As predicted by the modelling and Theorem 1 (Supplementary Information), in the absence of a private nutrient, invasion was blocked by the resident strain whether or not the invader carried the colicin antimicrobial (Fig. 2b,d,f). By contrast, in the presence of sorbitol as a private nutrient, the invading strain was able to establish itself (Fig. 2c,f). However, only when the invader had a private nutrient and it produced colicin E2 did we see strain displacement (Fig. 2e,g). A control experiment in which we did not supplement sorbitol confirms the dependency of displacement on the invader-specific private nutrient (Extended Data Fig. 6a–h). In addition, we confirmed that our results are robust for a colicin with a different killing mechanism, colicin K, which kills by forming pores in the outer membrane of the target strain19 (Fig. 2f,g and Extended Data Fig. 6i,j).

These first experiments therefore support our modelling predictions that strain displacement rests upon a combination of high interference competition but low resource competition.

Principles of strain displacement predict suppression of AMR isolates

Our first set of experiments were based upon a model strain of E. coli, which allowed us to modulate and isolate the type and strength of ecological competition using strains of the same genetic background. However, this approach is also artificial because competing bacterial strains in natural communities will often differ more extensively across their genomes. We therefore sought to test our modelling predictions in a second series of experiments that leverage natural variation in the degree of niche overlap between strains. Here we chose to focus on the potential to displace AMR E. coli strains, which are currently the dominant cause of AMR-associated deaths worldwide24. Leveraging natural competition mechanisms such as bacteriocin production is an interesting emerging alternative to antibiotics, because these mechanisms can be much more specific and less harmful to other microorganisms in a community21,22,23. In communities such as the mammalian microbiome, depletion of microbial diversity as a result of perturbations (that is, dysbiosis) such as antibiotic treatment is frequently associated with poor health outcomes1.

For the resident strains in our experiments, we identified three clinical isolates that are sensitive to colicin E2 in vitro. Two of them are human faecal E. coli isolates that produce extended-spectrum beta lactamases (ESBL; 0960 and 0268), which are in a large class of highly problematic AMR strains on the World Health Organization priority list24,40. The third isolate is a previously characterized beta lactamase-producing urine E. coli isolate (0018)17. For the invader strains, we chose five E. coli symbiont strains historically isolated from the faeces of healthy humans (Supplementary Table 1). The pangenome of E. coli is large and metabolic diversity between strains of E. coli is common39,43,44. To test whether this variability influenced strain invasion, we first studied the ability of the five invader strains to establish in a standard gut microbiome medium (modified Gifu anaerobic medium (mGAM), buffered to human colonic pH), which had been pre-inoculated with one of the three AMR E. coli isolates (Fig. 3a).

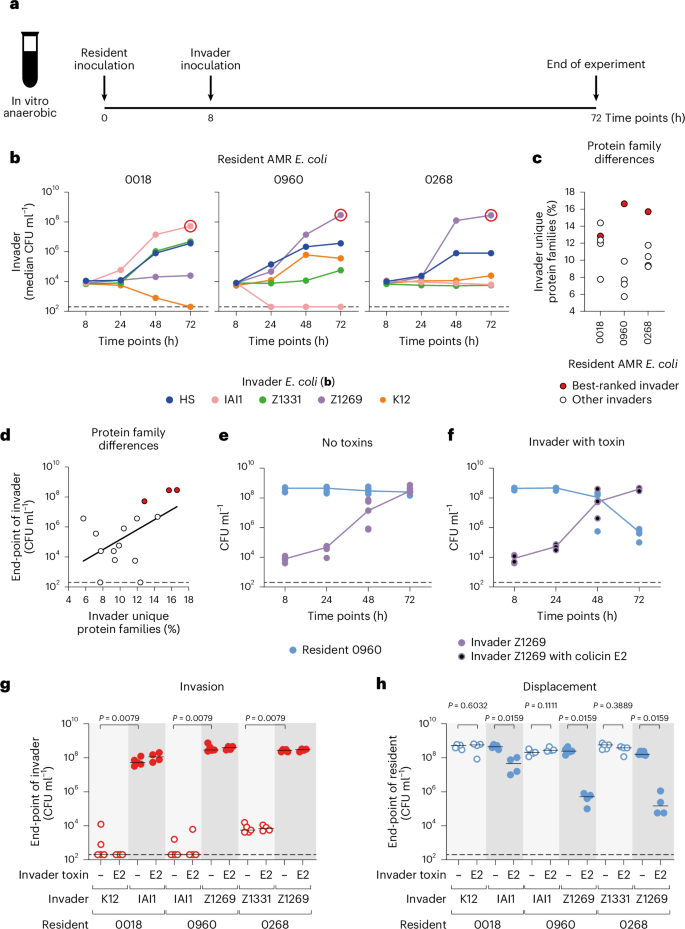

a, Scheme for invasion experiments using E. coli isolates. mGAM anaerobic medium in Hungate tubes is inoculated with one of three AMR isolates. After 8 h, one of five E. coli isolates from healthy humans is inoculated. Populations are enumerated using selective plating. b,Ecological invasion experiments according to the scheme in a. The median of N = 5 independent replicates for each invader (E. coli HS in blue, IAI1 in pink, Z1331 in green, Z1269 in purple, K12 in orange; all labelled with pACYC184 for chloramphenicol resistance) is shown at each sampled time point, and lines connect each median. Each E. coli isolate from healthy humans was tested for invasion into each AMR isolate (E. coli 0018, 0960 and 0268; ampicillin resistant). Dashed lines indicate the detection limits from selective plating. Red circles indicate the best-ranked invader for each AMR isolate. c, Protein family overlap between each pair of AMR isolate residents and invader isolates from healthy humans. For each pair, the percentage of protein families encoded by the invader that is not encoded by the resident is shown. For each AMR isolate, the best-ranked invader is highlighted in red (circled in b). d, Percentage of unique protein families for each strain pair (from c) against the end-point abundance of the invader after 72 h (data from b). Regression on log-transformed data and a line of best fit is shown (black line). Coefficient of determination (R2) = 0.2833, slope significantly different than 0 (Spearman’s rank correlation one tailed, P = 0.0230; Pearson correlation one tailed, P = 0.0206). The dashed line indicates the detection limit from selective plating. Strains highlighted in red in c are also indicated. e, The same data in b are replotted only when the resident is E. coli 0960 (blue) and the invader is E. coli Z1269 (purple). Each data point is an independent biological replicate (N = 5), and the lines connect the medians for each time point. f, The same experiment as in e is repeated, but E. coli Z1269 contains colicin E2 (colicin plasmid labelled with chloramphenicol resistance; purple circles with black fill). Each data point is an independent biological replicate (N = 4) determined by selective plating, and the lines connect the medians for each time point. g,h, Ecological invasion experiments as in e and f are performed for each of the best-ranked (dark grey background shade) and worst-ranked (light grey background shade) invader for each AMR isolate (N = 5 biological replicates from independent experiments for each strain pair without colicin E2, and N = 4 for each strain pair with colicin E2). The end-point abundance of the invaders is plotted in g, and the end-point abundance of the residents is plotted in h. Lines indicate medians. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare the population sizes of the best- and worst-ranked invaders for each AMR resident in g and to compare the population sizes of the resident when the invader either does or does not contain colicin E2 in h. In e–h, dashed lines indicate the detection limits from selective plating.

Consistent with metabolic diversity among the strains, the outcome of the invasion experiments depends upon the combination of strains under study (Fig. 3b). Importantly, the experiments do not identify a single strain that is the best at invading, nor one that is best at blocking invasion. For example, E. coli Z1269 invades well into E. coli 0960 and 0268 but poorly into E. coli 0018. These patterns are consistent with our modelling in which invasion is dependent upon the metabolic niche available to each of the two strains. Previous work from our laboratory found that nutrient niche overlap between bacterial species in co-culture can be predicted from the degree of overlap in their protein families17. To explore this here, we turned to the genome sequences of the eight E. coli strains. We can calculate the proportion of protein families encoded by an invading strain that are not encoded by a given resident strain for each pairwise combination. Our overlap calculations reveal a significant positive relationship between the genomic difference (that is, predicted nutrient niche difference) between strains and the ecological success of the invader (Fig. 3c,d). This result is again consistent with the modelling prediction that invasion is enabled by metabolic niche diversity between an invader and resident strains, which is further supported below where we turn phenotypic data on the carbon sources that different strains and species use.

We next investigated what happens when an invader strain is also capable of interference competition. As a test case, we equipped one of our invader strains (Z1269) with colicin E2 and performed the same invasion assay into E. coli 0960 as before. As expected from previous results, without the antimicrobial, Z1269 invaded well but did not displace the resident strain E. coli 0960 (Fig. 3e). By contrast, with the antimicrobial, Z1269 could both invade and markedly reduce the number of the AMR strain (Fig. 3f). We then extended the experiments to include the best-ranked invader and worst-ranked invader for each of the three AMR E. coli isolates. In all cases, when a best-ranked invading strain produced colicin E2, it was able to both invade (Fig. 3g) and suppress the AMR E. coli isolate (Fig. 3h and Extended Data Fig. 7). Importantly, and consistent with Theorem 1 (equation (2) and Supplementary Information), all the worst-ranked invading strains were unable to invade whether or not they carried the antimicrobial colicin (Fig. 3g). In summary, in competitions between natural isolates of E. coli, we find again that strain displacement rests upon the combination of expected low nutrient competition and high interference competition.

Overcoming nutrient blocking enables strain displacement in diverse bacterial communities

We have so far studied competition scenarios in which an invading strain faces a resident strain of the same species in isolation. However, many microbial communities contain a diversity of species. These species can interact with one another in ways that affect ecological outcomes8,45. Therefore, we next performed E. coli invasion experiments in the presence, or absence, of a diverse community, focusing on the best-ranked invading strain for each AMR E. coli isolate. For the community, we chose a community of 15 species that we had previously characterized and contains phylogenetically distinct representatives of common human gut symbionts17. We grew each symbiont species separately, assembled them in 15-species communities along with the resident AMR E. coli isolate and then challenged the resulting community with the best-ranked invader (Fig. 4a). Note that colicin E2 is a narrow-spectrum bacteriocin, meaning that the community is not expected to be directly affected by its action23. As expected from the last set of experiments, when the community was absent, all invaders established themselves in the presence of the resident (Fig. 4b) and suppressed its numbers (Fig. 4c). However, the outcome changed in the presence of the community. Adding the 15-species community always blocked the invader from establishing (Fig. 4b) and consequently also blocked any displacement (Fig. 4b,c and Extended Data Fig. 8).

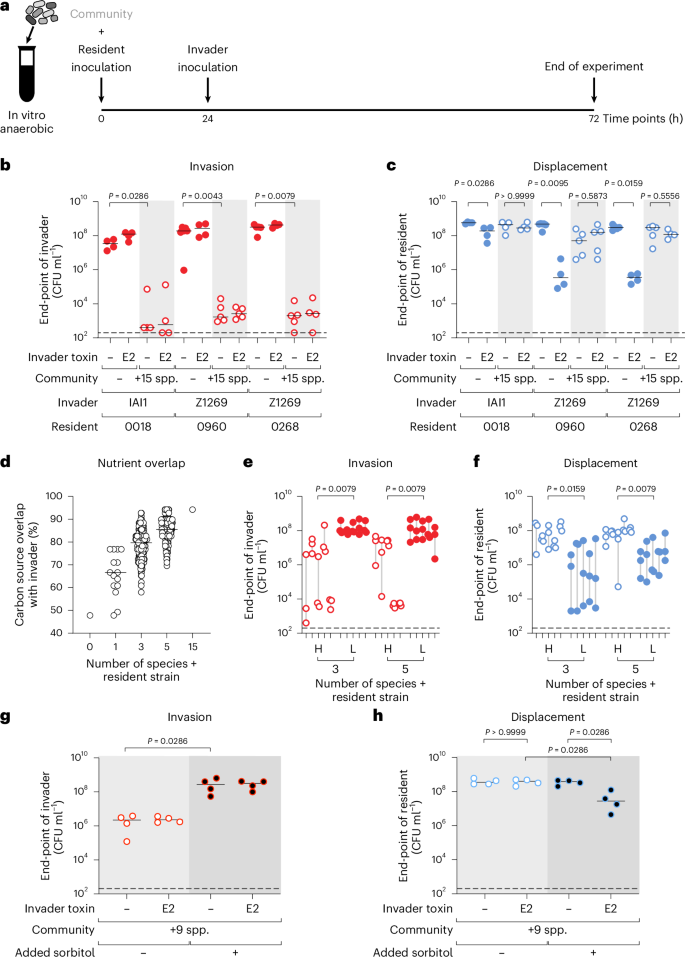

a, Scheme for community invasion experiments. b,c, Experiments as in a are performed for the best-ranked invader for each AMR isolate (from Fig. 3b) in the absence (white background; red filled circles) or presence (light grey background shade; open red circles) of a 15-member community (+15 spp.; see Supplementary Table 1 for strains used). For each strain pair, the invader either contains colicin E2 or remains the wild-type E. coli invader. N = 4 biological replicates from independent experiments for all combinations, with the exception of N = 5 for four combinations (Z1269 and 0960 in the presence of 15 species both when Z1269 does and does not have colicin E2; Z1269 and 0268 when Z1269 does not have a toxin, both in the absence of a 15-species community), and N = 6 for the strain pair of Z1269 and 0960 in the absence of a community and colicin E2. The end-point abundance of the invaders is plotted in b, and the end-point abundance of the residents is plotted in c. Lines indicate medians. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare the population sizes of invaders in b and to compare the population sizes of the resident in c. Dashed lines indicate the detection limits from selective plating. d, In silico prediction of carbon-source overlap of the resident AMR E. coli 0960 and the community to the invader E. coli Z1269. Each circle represents a different community and all possible combinations of the 15 species in addition to the focal strain pair at each diversity level is plotted (N = 1, N = 15, N = 455, N = 3,003, N = 1 for 0, 1, 3, 5 and 15 additional species, respectively). AN Biolog assays are used to determine carbon source overlap of each individual strain (Extended Data Fig. 9a), and predicted carbon-source overlap of the community is calculated using an additive approach as done in ref. 17. e,f, The effects on invasion and displacement of five communities with the highest (H; open red circles) and lowest (L; filled red circles) overlap to the invader at diversity levels of both three and five species in addition to the focal E. coli strains were tested (communities identified in d). For each of the five communities in each group, N = 3 biological replicates from independent experiments are shown and grey lines connect the highest and lowest point of the three replicates. Dashed lines indicate the detection limits from selective plating. The end-point (72 h) abundance of invader E. coli Z1269 is plotted in e, and the end-point abundance of resident E. coli 0960 is plotted in f. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare the end-point of the invader in e with the end-point of the resident in f. In all cases, the median value of the three replicates for each community is used. This means that Mann–Whitney U tests use community medians for the comparisons (N = 5 communities for each). g,h, Nutrient supplementation experiment in the presence of a diverse community. The AMR isolate E. coli 0018 ∆srlAEB is the resident and embedded in a community of 9 species that cannot use sorbitol (+9 spp.; see Supplementary Table 1 for strains used; inability to use sorbitol defined in Extended Data Fig. 9a). One-half mGAM medium without (light grey background shade; open circles) or with 1% sorbitol (dark grey background shade; circles with black fill) is used as the medium. The invader strain is E. coli IAI1 with or without colicin E2. N = 4 biological replicates from independent experiments. The end-point (72 h) abundance of the invader is plotted in g, and the end-point abundance of the resident is plotted in h. Two-tailed Mann–Whitney U tests are used to compare the end-point abundance of the invader in g, and to compare the end-point abundance of the AMR E. coli resident in h.

This impact of the community is consistent with previous work showing that diverse communities can block invasion of pathogens collectively. This process, known as nutrient blocking, occurs whenever there is sufficient overlap in the nutrient utilization abilities of the community as a whole compared with the invading strain17. To explore the importance of nutrient blocking, we focused on the case of the invading strain E. coli Z1269 and the AMR E. coli isolate 0960. We use previously published data on the nutrient utilization abilities of the 15 symbionts from Biolog AN MicroPlates (Extended Data Fig. 9a)17 and also collected Biolog data for the E. coli strains for the purposes of this study, which revealed that E. coli 0960 could metabolize only around half of the carbon sources on the plate used by E. coli Z1269 in these experimental conditions (Fig. 4d). Not all carbon sources in our growth media are found on the Biolog plates, and vice versa. Nevertheless, previous work found that the Biolog plates are a good proxy for general carbon source overlap between strains17. We computationally assembled all possible combinations of 1, 3 and 5 species for the other 15 symbionts and calculated the carbon source overlap between these communities (when they also contain the E. coli resident) and the invading strain E. coli Z1269. As the diversity of the community increases, we observe that the probability of community-conferred carbon source overlap with the invading strain is higher, again consistent with previous work17 (Fig. 4d). Importantly, when all 15 species are present, the community can metabolize nearly all tested carbon sources compared with the invading strain. This suggests that high metabolic overlap explains why the 15-species community blocked invasion and consequent displacement in our experiments (Fig. 4b,c).

We further tested the importance of nutrient blocking by using our carbon-source overlap calculations to identify three- and five-species communities which, when added to the resident E. coli strain, have either the highest or lowest overlap with the invading strain. Specifically, for each level of diversity, we chose five communities that had the highest overlap (H) and five communities that had the lowest overlap (L) and then performed the same experiment as before (Fig. 4a). As predicted, the invader invaded effectively when the community was predicted to have low overlap relative to the invader, but failed to invade reliably when the community was predicted to have high overlap (Fig. 4e). Importantly, this led to efficient displacement of the resident in the low-overlap communities but not in the high-overlap ones (Fig. 4f). Moreover, displacement never occurred when the invader lacked the ability to make colicin antimicrobials (Extended Data Fig. 9b,c). These experiments, therefore, again support the importance of nutrient blocking for strain displacement. Specifically, for displacement to occur in our experiments, an incoming strain must be able to overcome both nutrient competition from conspecific strains in its niche as well as collective nutrient blocking that involves multiple members of the resident community.

As a final test of our ideas, we asked whether one can overcome nutrient blocking of an invading strain and drive strain displacement by supplementing with a private nutrient. We ran a version of our invasion experiment using a community of nine species that cannot metabolize sorbitol. We used genome editing to generate a ∆srlAEB mutant, which cannot use sorbitol, in the background of the AMR E. coli isolate 0018 and used this as the resident strain. As a result, no member of the resident community can use sorbitol in this experiment. E. coli IAI1 was the invading strain with colicin E2 for interference competition. This strain normally invades well and displaces E. coli 0018 in the absence of a community (Fig. 4b,c). By contrast, in the presence of the nine-species community, we observe nutrient blocking and poor invasion (Fig. 4g), without an observable impact on E. coli 0018 (Fig. 4h). However, as predicted, the addition of sorbitol as a private nutrient drives an increase in invasion by ~100-fold (Fig. 4g) and the suppression of the AMR E. coli target strain within the community of 9 species (Fig. 4h). We confirmed that this result is dependent on sorbitol not being consumed by the community: when E. coli 0018 can use sorbitol (E. coli 0018 wild type used as the resident), E. coli IAI1 could no longer invade, even under sorbitol supplementation (Extended Data Fig. 10). In summary, the results from diverse communities of bacteria again support our modelling predictions that competitive strain displacement rests upon weakening nutrient competition in order that an invading strain can establish and engage in interference competition that suppresses a resident strain.

First Appeared on

Source link