Drug-resistant bacteria threat grows; Detroit risks high

The World Health Organization sounded the alarm Monday about a growing threat of drug-resistant bacteria around the globe that could undermine life-saving treatments, an issue Wayne State University researchers have been warning about for years.

One in 6 laboratory-confirmed bacterial infections that led to common infections in people worldwide in 2023 were resistant to antibiotic treatments, according to a WHO report released Monday that reviewed data from more than 100 countries. From 2018-23, antibiotic resistance increased in more than 40% of the pathogen-antibiotic combinations monitored, rising to more than 70% in some African nations, the report found.

This growing threat to global health, including in the United States, compromises the ability of antibiotics and other drugs to treat infections and protect patients during surgeries, said WHO officials, who called the growing resistance to antibiotics “widespread, increasing and unevenly distributed.”

“Antimicrobial resistance is outpacing advances in modern medicine, threatening the health of families worldwide,” WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a Monday statement.

The threat is particularly acute in Detroit, researchers say, due to a combination of social and health issues.

While the situation in the United States is not as bad as in other countries, six bacterial antimicrobial-resistant infections increased by a combined 20% in U.S. hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the pre-pandemic period, according to a July 2024 U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention report. The reported number of clinical cases of Candida auris — a type of yeast that is resistant to antifungal medications and can spread in health care facilities — increased almost fivefold from 2019 to 2022, the CDC found.

“We are so interconnected, and organisms spread very easily,” Michigan Chief Medical Executive Natasha Bagdasarian told The Detroit News on Monday. “There are different patterns depending on place, but the (drug-resistant bacteria) are really everywhere. What’s happening on the other side of the globe really impacts us here.”

More than 2.8 million antimicrobial-resistant infections occur each year in the United States, according to the CDC, which added that its 2019 report found that more than 35,000 people die as a result. Antimicrobial-resistant infections were associated with nearly 5 million deaths worldwide in 2019, according to a report released in The Lancet medical journal.

Wayne State researchers have been studying the impacts of drug-resistant bacteria for years, after drug-resistant bacteria were found among Detroit patients, said Dr. Teena Chopra, an assistant dean in the Wayne State School of Medicine, where she is an infectious diseases expert. She and other Wayne State experts have been stressing it is critical to stop the spread of the drug-resistant bacteria, especially in Detroit and southeast Michigan.

“It’s been getting worse for years now,” Chopra said Monday. “Drug resistance is here … and, given the population of Detroit who are on antibiotics, it’s one of the biggest problems.”

Detroit is one of America’s most impoverished big cities, with a majority Black population that has more chronic health conditions. One of the first reported outbreaks of drug-resistant bacteria occurred in Detroit in the early 1980s, involving intravenous drug users and other patients with medical conditions.

Ghebreyesus warned that doctors around the globe need to use antibiotics responsibly, since an overreliance on antibiotics to treat a variety of ailments has helped lead to the crisis.

“Our future also depends on strengthening systems to prevent, diagnose and treat infections and on innovating with next-generation antibiotics and rapid point-of-care molecular tests,” he said.

Impacts of drug-resistant bacteria

Detroiters have higher percentages of obesity, diabetes and blood pressure, Chopra said. These conditions require a person to be on antibiotics to treat them, she said. If the antibiotics aren’t as effective, people could die of the diseases, she said.

People with other infections, such as those of the bloodstream, urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, are also at risk of being exposed to drug-resistant bacteria.

In its report, the WHO examined worldwide resistance to 22 antibiotics used to treat common infections. From 2018 to 2023, antibiotic resistance increased an annual average of 5% to 15% in the monitored antibiotics, the report found.

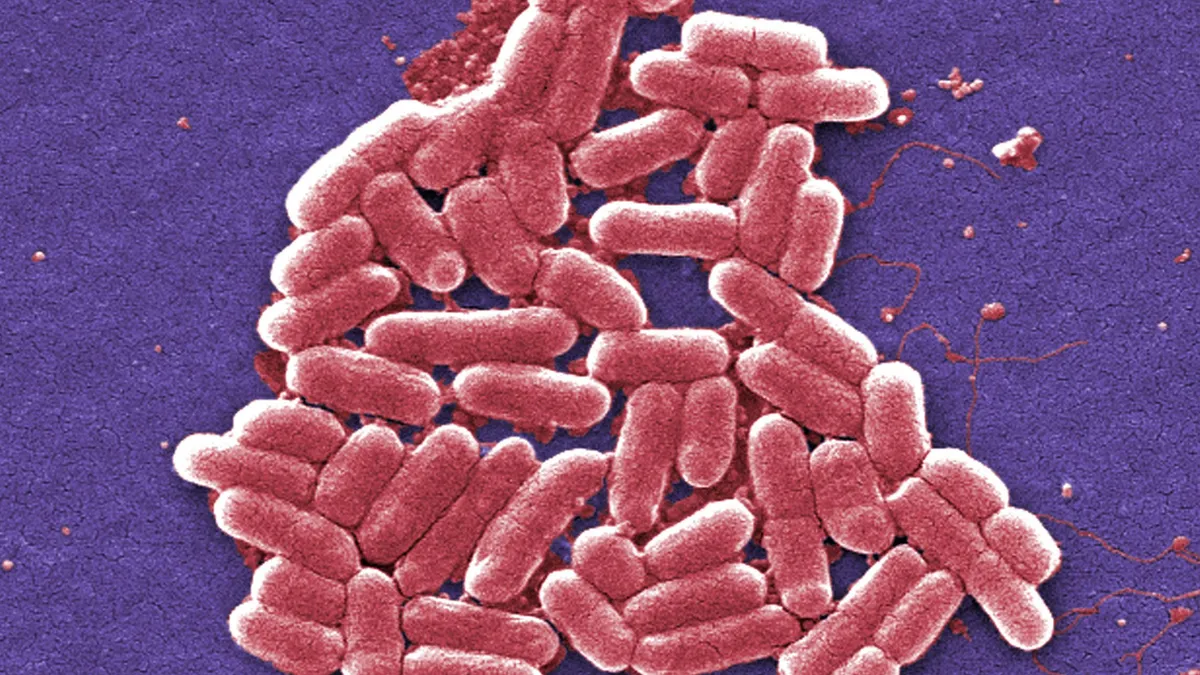

The WHO report also looked at eight common bacterial pathogens worldwide, including E. coli and K. pneumoniae, which can lead to severe bloodstream infections that frequently result in sepsis, organ failure and death. The report found that 40% of E. coli infections and 55% of K. pneumoniae infections globally are now resistant to third-generation cephalosporins or a form of antibiotics that includes penicillins, which are the first-choice treatment for these infections.

The CDC said last month that infections of a type of drug-resistant bacteria called NDM-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales have surged more than 460% in the United States between 2019 and 2023.

The estimated U.S. cost to treat infections caused by six antimicrobial-resistant germs frequently found in health care is more than $4.6 billion annually, according to a CDC study.

Across the world, the WHO report estimated that antibiotic resistance is highest in the South-East Asian and Eastern Mediterranean regions, where 1 in 3 reported infections was resistant. The South-East Asian region covers a quarter of the globe’s population, while the Eastern Mediterranean area covers countries such as Afghanistan, Egypt, Tunisia and Pakistan, or about 10% of the world’s population.

In the African region, 1 in 5 infections was resistant.

Causes of drug-resistant bacteria

The increased use and misuse of antibiotics or antimicrobials, along with other stressors, such as pollution, create conditions for microorganisms to develop resistance and bacteria in water, soil and air can become resistant to common antibiotics following contact with resistant microorganisms, the WHO report said.

“As soon as antibiotics started, bacteria developed to be able to resist them,” Michigan’s Bagdasarian said. “Now multiple different classes of bacteria can resist them.”

The exposure to the bacteria can occur through contact with polluted waters, contaminated food, the inhalation of fungal spores, and other pathways.

Wayne State’s Chopra added that the increased use of antibiotics for farm livestock has also increased the number of drug-resistant bacteria.

Social disparities also lead to some areas like Detroit being higher in drug-resistant bacteria, Chopra said. People who lack access to doctors are more likely not to seek treatment, which allows the bacteria to become a more serious problem and potentially spread, she said.

An outbreak of community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus, or a drug-resistant bacterium, was reported as early as 1982 in Detroit, where more than half of the patients were intravenous drug users, and the other half had medical conditions that also put them at risk, according to a paper by the Infectious Disease Clinics of North America.

The proportion of community-acquired staphylococcal infections resistant to methicillin rose from 3% in March 1980 to 38% in September 1981 among 165 patients seen at Henry Ford Hospital in Detroit, according to a 1982 paper published in the Annals of Internal Medicine. “Drug abuse, serious underlying illness, previous antimicrobial therapy, and previous hospitalization were all associated with the development of this infection,” according to the paper’s abstract.

Other strains of drug-resistant bacterium were also discovered during this outbreak, according to a paper in the National Library of Medicine.

What can be done

Although the number of countries reporting bacteria-resistance issues has ballooned fourfold to 104 countries since 2016, almost half of the countries did not report data in 2023, the WHO said. And it warned that about half of the reporting countries still lacked the systems “to generate reliable data.”

Generating more reliable data, especially in underserved areas, by 2030 can help inform treatments and policies to fight this public health threat, according to the WHO.

For patients, Chopra said, only use antibiotics when prescribed by health care professionals and take all of the prescribed antibiotics.

But she also pointed to sweeping changes she believes could help slow the rise of the bacteria. Legislation requiring scientists to check for and report the bacteria, worldwide standards on the use of antibiotics for livestock and more federal funding for research to treat the infections would help, she said.

Investments in and creating incentives for the creation of novel antibiotics that bacteria haven’t yet formed a resistance to is another solution, Chopra and Bagdasarian said.

Another solution is antibiotic stewardship, which is already common in most U.S. hospitals, Bagdasarian said. This is a program in which doctors and pharmacists learn the appropriate use of antibiotics to prevent resistance, improve patient outcomes, and preserve antibiotic effectiveness.

For those suffering from an infection or showing symptoms, such as fever, a headache or fatigue, Chopra suggested seeing a primary care physician as soon as possible.

“The faster we see it, the faster we can treat it,” she said. “Any delays in detection could make it harder to treat and cause it to spread.”

But this time of year, especially, it’s important to make sure patients are being treated for the right condition, Bagdasarian said. Viral infections can’t be treated by antibiotics, and using antibiotics to treat respiratory infections will lead to overuse, she said.

“We want to avoid a future where we have bacterial infections that we can’t treat,” Bagdasarian said.

First Appeared on

Source link