Scientists Uncover the Oldest Skin Ever Found in an Oklahoma Cave — It’s Over 290 Million Years Old

A tiny fragment of skin, dating back 290 million years, may seem unbelievable, but that’s exactly what researchers in Oklahoma have discovered, a fossil from an era long before dinosaurs even existed. The original study, published in Current Biology, reveals that although the skin is smaller than a fingertip, it is astonishingly well-preserved. It’s a rare occurrence for soft tissue like this to survive for nearly 300 million years.

An Ideal Cave for Preservation

The discovery took place in Richards Spur, a cave in Oklahoma already known for its rich collection of fossils. What makes this site special is that the combination of low oxygen levels, fine sediment, and oil seepage from nearby shale created exceptional conditions for preservation. And when we talk about preservation, it’s really a stroke of luck, conditions like these are like a natural vault for fossils. As Ethan Mooney, one of the study’s authors, put it, “It’s completely unlike anything we would have expected.”

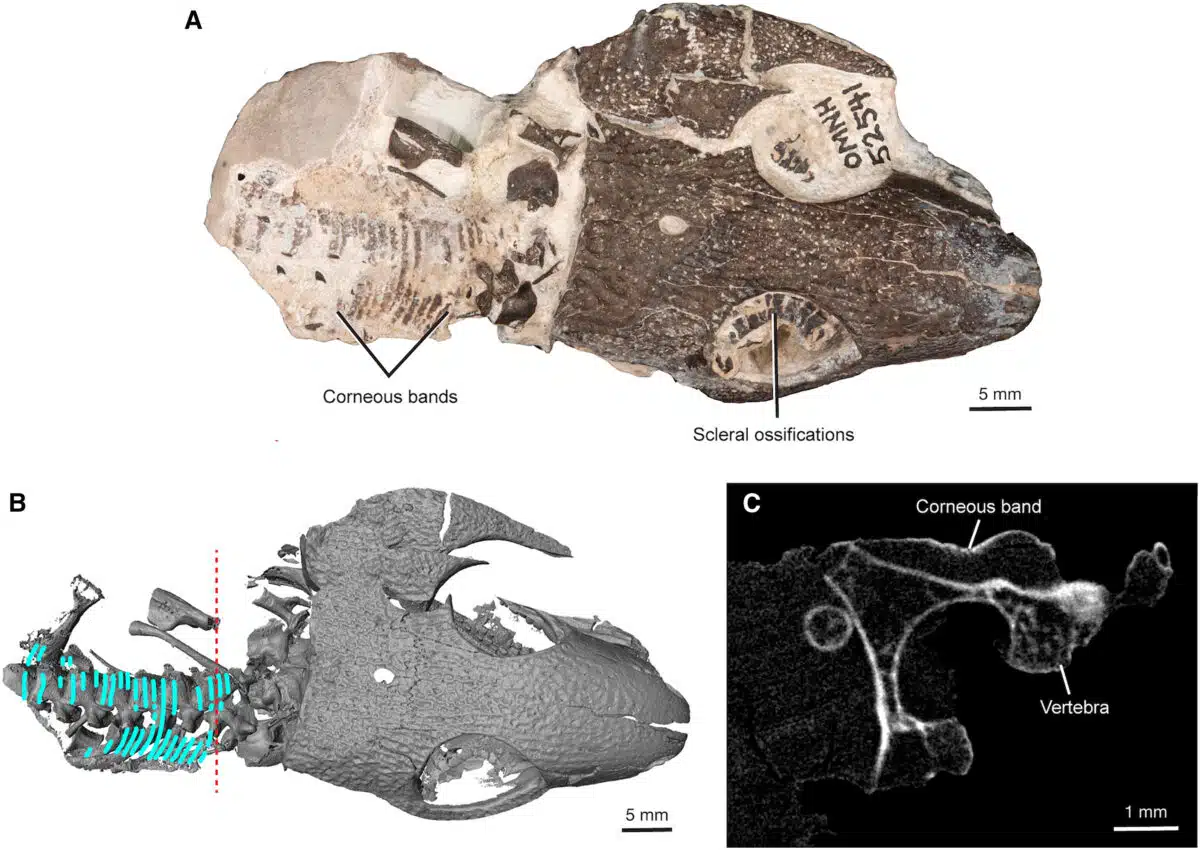

As stated in the study, the pelt was found in 2018 along with other fossils, but it stands out for its remarkable 3D preservation. The presence of petroleum and tar in the cave likely played a key role in preventing the hide from decaying over millions of years.

Fossilized Skin with Reptilian Features

The piece of skin, only a few millimeters in size, has a pebbled texture similar to that of crocodile skin. According to the researchers, there are areas between the epidermal scales that resemble what we see in modern snakes and lizards. This suggests that even back then, this skin likely played an important role in protecting the reptile.

The scientists also discovered epidermal tissues, typical of amniotes—a group that includes reptiles, birds, and mammals. This indicates that the skin was not just a simple outer layer, but a vital protective barrier against the elements. If you’ve ever wondered how modern reptiles survive extreme heat, freezing temperatures, or injury.

While the exact species of the reptile remains unclear, researchers believe it could be Captorhinus aguti, a Permian reptile previously found in the cave. This hypothesis seems plausible, as the skin’s texture aligns with what is known about this species.

“This cave system was also an active oil seepage site during the Permian, and interactions between hydrocarbons in petroleum and tar likely played a key role in preserving this skin,” noted the researchers.

First Appeared on

Source link