What Experts Found Left Them Speechless

For over five years, a Kansas family unknowingly lived with thousands of brown recluse spiders, one of North America’s most feared venomous arachnids. They shared their home with more than 2,000 individuals—some nesting in closets, behind baseboards, even on bedding. Yet despite this heavy infestation, not one of the four residents suffered a confirmed bite.

The discovery, published in the Journal of Medical Entomology, challenges a central fear surrounding Loxosceles reclusa: that proximity alone poses a serious threat to humans. The spiders were meticulously counted and tracked over a six-month period, with no signs of injury to the occupants—despite frequent direct contact.

This surprising case, documented by Richard S. Vetter of the University of California, Riverside, is reshaping how experts think about risk perception, spider behavior, and public health messaging around spider bites.

More Spiders, Less Danger?

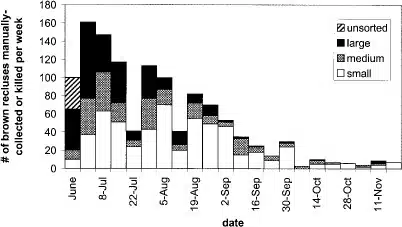

Between sticky traps and hand-collection, researchers retrieved 2,055 brown recluse spiders from the Lenexa, Kansas home. Of those, 1,213 were manually captured—323 classified as large, 255 medium, and 601 small. The remaining 842 were caught passively on sticky traps.

Vetter, a noted arachnologist with over 120 scientific contributions, noted that approximately 400 of the spiders were physically capable of delivering a medically significant bite. And still—no one in the home reported symptoms consistent with recluse envenomation.

The research emphasized that brown recluses are not aggressive, rarely bite, and often flee or remain motionless when disturbed. According to the published study:

“Even in a house with hundreds of potentially biting-sized recluses, there were no envenomations… This supports the notion that L. reclusa does not readily bite humans.”

That’s despite two family members conducting nightly spider collections, handling bedding, and frequently coming into accidental contact with the spiders.

The Myth of the Deadly Recluse

The brown recluse has long been at the center of public paranoia, frequently blamed for mysterious skin lesions, necrotic wounds, and even fatal bites. Yet most of those fears aren’t supported by verifiable science.

As Vetter explains in the study, brown recluse bites are frequently misdiagnosed, particularly in regions where the spiders do not occur. Verified bites outside of the spider’s native range—limited to parts of the Midwest and South—are rare and almost never confirmed by specimen identification.

Misidentification is a serious issue. The study emphasizes:

“The diagnosis of brown recluse spider bite is overused for skin sores with unclear causes… mislabels can delay correct treatment for infections or other conditions.”

The clinical implications are real. In areas like California or New York—where brown recluses are not native—doctors have sometimes prescribed aggressive treatments (including surgery) for “spider bites” that were, in reality, unrelated infections or autoimmune conditions.

The full study, titled An Infestation of Brown Recluse Spiders: Fact Versus Fear, underscores the danger of diagnostic shortcuts. It urges clinicians to seek proof—namely, a captured spider identified by an arachnologist—before attributing skin lesions to recluse envenomation.

Recluse by Name, Recluse by Nature

The Kansas case stands out not just for its scale, but for its clarity: even under sustained human-spider proximity, there was no aggression.

Brown recluses are nocturnal, favor dry and undisturbed spaces, and use venom primarily to subdue insects—not defend against humans. The study found that smaller spiders were more likely to be trapped, while larger specimens appeared early in the season and were eventually reduced through manual collection.

This matches Vetter’s broader body of research on spider behavior. In Integrated Pest Management of the Brown Recluse Spider, he emphasizes that population control is possible through basic non-chemical interventions: decluttering storage areas, using sticky traps, and sealing baseboards or wall cracks.

Vetter also works closely with the University of California, Riverside, where his team conducts ecological and medical entomology research. His studies routinely highlight how public misinformation has inflated the perceived threat posed by spiders.

What This Changes—And What It Doesn’t

The Kansas infestation doesn’t render brown recluses harmless. Their venom can cause tissue damage in rare cases, and caution remains warranted, especially for those living in the spider’s native range. Gloves should be worn in storage areas, and spiders should not be handled.

But the data demands a shift in perspective: presence does not equal threat. Even when cohabiting with hundreds of capable spiders, humans may remain untouched—if not oblivious. Fear, the study implies, is often rooted more in imagination than in interaction.

Public health guidance and medical training may need to catch up. As misdiagnosis continues to proliferate online and in clinics, the call from experts like Vetter is clear: respect spiders, don’t misrepresent them.

First Appeared on

Source link