Frozen Creature Comes Back to Life After 46,000 Years… and Picked up Right Where It Left Off

Deep beneath the Siberian permafrost, scientists revived a microscopic worm frozen in suspended animation for nearly 46,000 years. The tiny nematode, entombed inside ancient rodent burrows preserved in permafrost, stirred back to life in a lab and even began to reproduce.

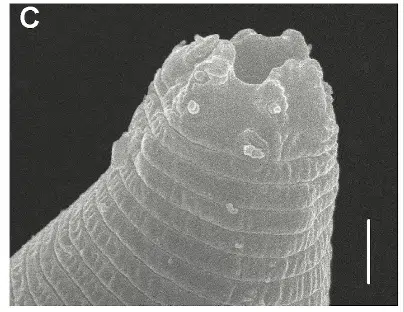

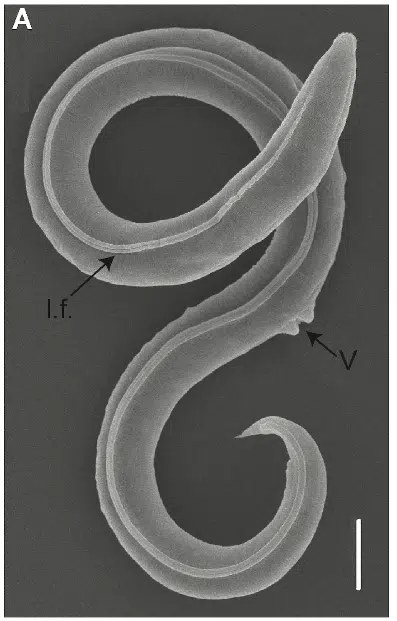

What makes this more than a biological curiosity is what it reveals about the extreme limits of life. The worm, identified as a new species named Panagrolaimus kolymaensis, was radiocarbon dated to the late Pleistocene era, a time when woolly mammoths still roamed.

Its survival suggests a level of biological resilience once thought impossible. More than that, its genetic mechanisms may hold clues for organ preservation, biomedical science, and deep-space survival.

A New Species Revived from the Permafrost

The nematode was unearthed from a fossilized gopher burrow roughly 40 meters below the surface near the Kolyma River in northeastern Siberia. Through accelerator mass spectrometry, researchers determined the surrounding plant material was approximately 46,000 years old, placing the worm’s last active moment well before the rise of modern civilization.

In a detailed peer-reviewed study published in PLOS Genetics, scientists confirmed that the organism is a previously undescribed species. It shares a genus with other nematodes known for surviving extreme desiccation and freezing.

The research team, led by experts from the University of Cologne and the Pushchino Scientific Center in Russia, sequenced the worm’s genome and found it to be triploid, meaning it carries three copies of its genetic material. The species also reproduces asexually, a trait that likely aided its survival in complete isolation.

The worm’s return to activity wasn’t just a fluke—it resumed feeding and reproduced in laboratory conditions, proving not only viability, but full metabolic recovery after tens of thousands of years in cryptobiosis.

Cryptobiosis: The Biological Pause Button

The key to the worm’s survival lies in a process called cryptobiosis, a state in which all metabolic activity halts and life is essentially placed on pause. Scientists have long known that some species can enter this state to survive temporary drought or cold—but the long-term viability seen in P. kolymaensis dramatically expands those timelines.

In laboratory experiments, the worm demonstrated molecular mechanisms also found in the model nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. These include trehalose synthesis and the glyoxylate shunt, both of which help protect cells during desiccation and freezing by replacing water and reducing metabolic stress.

The genome of P. kolymaensis revealed many of the same stress-response pathways found in C. elegans, suggesting that these mechanisms evolved millions of years ago and may be shared across multiple nematode lineages.

Comparable biological strategies have been documented in tardigrades, microscopic animals also capable of surviving in space, high radiation, and extreme dehydration. NASA has even explored tardigrades in orbit: in a 2021 space station experiment, researchers sent them aboard a SpaceX cargo mission to study how they respond to microgravity and cosmic radiation.

How Ancient Biology Could Shape the Future of Medicine and Spaceflight

The implications of this research reach far beyond frozen soil. If scientists can isolate and apply the biochemical strategies used by P. kolymaensis, it could transform cryopreservation, allowing organs or even whole organisms to survive freezing for extended periods without damage.

This has immediate relevance for transplant medicine, where current preservation methods offer only short windows before tissue degradation. With trehalose-based vitrification and cryptobiosis-like processes, preservation could potentially stretch into weeks or longer.

The worm’s revival also matters to space exploration. Human missions to Mars or deep space face critical hurdles in storing biological material and protecting life from radiation and freezing. The survival toolkit used by extremophiles like P. kolymaensis may one day inform how astronauts, cells, or even embryos are kept viable on multiyear journeys beyond Earth.

Further studies will aim to map out the full range of cryptobiotic capabilities in nematodes, especially under combined stress conditions like dehydration and freezing—conditions mimicking icy moons or Martian regolith.

First Appeared on

Source link