Scientists Find Earth’s Oldest Rocks, And They Just Changed Everything We Thought About Continents

A new study published in Nature Communications reveals that some of Earth’s oldest rocks, dating back 3.7 billion years, challenge long-standing theories about the formation of the planet’s earliest continents, and even strengthen the connection between Earth and the Moon.

A Radical Reassessment Of Earth’s Earliest Crust

A team of researchers led by PhD candidate Matilda Boyce from the University of Western Australia has uncovered surprising isotopic evidence hidden inside ancient rocks from the Murchison region of Western Australia. The rocks in question, anorthosites, which are extremely rare on Earth, have yielded isotopic fingerprints that indicate Earth’s continental crust may have started forming significantly later than previously thought. According to the study, which appeared in Nature Communications, Earth’s continents began to grow around 3.5 billion years ago, nearly a billion years after the planet itself formed.

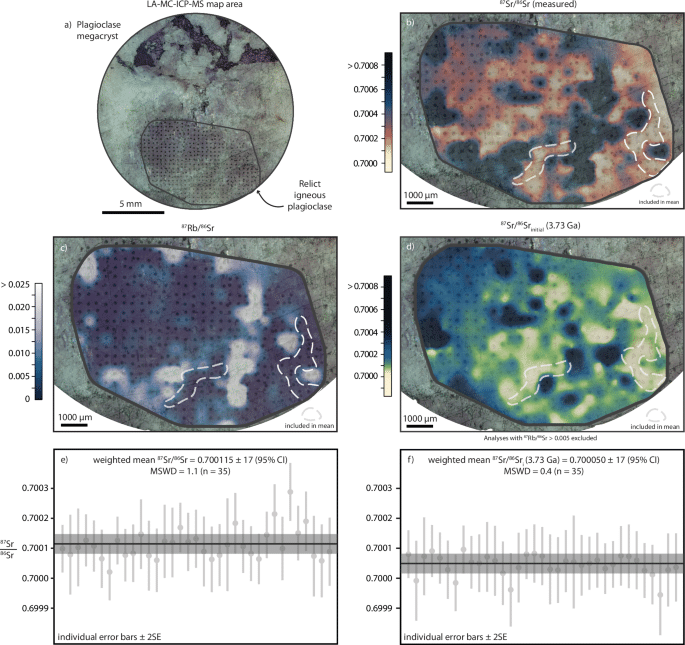

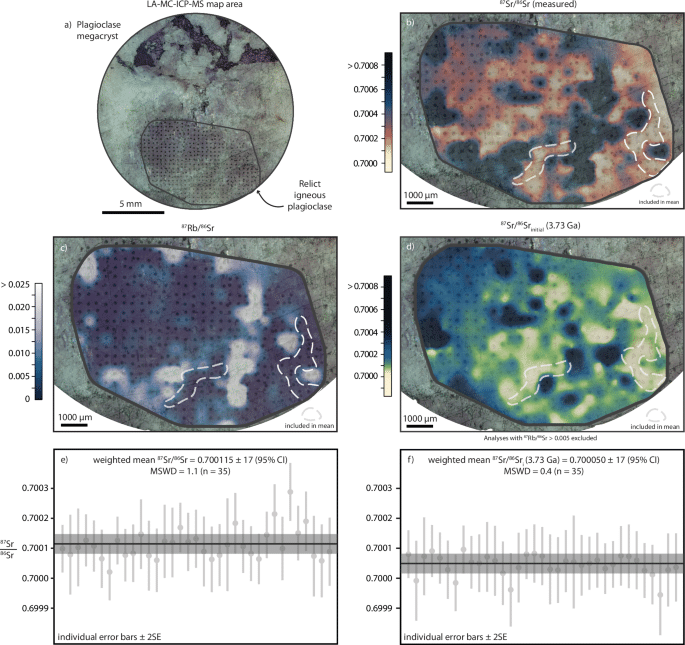

Boyce and her team focused on plagioclase feldspar crystals embedded within these rocks, using advanced analytical techniques to extract the isotopic history of Earth’s mantle. “The timing and rate of early crustal growth on Earth remains contentious due to the scarcity of very ancient rocks,” Boyce said. The team’s work adds weight to a more delayed timeline of continental development, pushing back against long-held assumptions of rapid early crust formation in the Hadean and early Archean eons.

Hidden Messages In The Oldest Crystals On Earth

To peer into Earth’s earliest geological history, the researchers targeted untouched fragments of feldspar, a mineral that can preserve pristine isotopic signatures even after billions of years. By isolating the freshest regions of these minerals, they obtained strontium and calcium isotopic data that trace the depletion of Earth’s mantle, essentially mapping when material from the Earth’s interior began forming continents.

“We used fine-scale analytical methods to isolate the fresh areas of plagioclase feldspar crystals, which record the isotopic ’fingerprint’ of the ancient mantle,” Boyce explained. This method revealed that continental crust formation ramped up around 3.5 billion years ago, much later than what many models of early Earth had proposed.

The scarcity of such ancient rocks makes each sample invaluable. These results offer a new baseline for understanding how long Earth remained a mostly oceanic world before permanent continental landmasses began to take shape. The implications stretch far beyond geological curiosity, they reshape our understanding of the Earth’s surface evolution, atmosphere development, and possibly even early life.

From Earth To The Moon: A Shared Cosmic Origin

The study’s implications extend beyond our planet. The team compared isotopic measurements from the Australian anorthosites to samples brought back from the Moon during NASA’s Apollo missions. Despite being worlds apart, the chemical similarities were striking. “Anorthosites are rare rocks on Earth but very common on the Moon,” Boyce noted. The research found that both the Earth and Moon seem to have emerged from the same starting material, dated to approximately 4.5 billion years ago.

“Our comparison was consistent with the Earth and Moon having the same starting composition of around 4.5 billion years ago,” Boyce added. This result lends support to the Giant Impact Hypothesis, a widely accepted theory that the Moon formed after a Mars-sized object collided with the early Earth, flinging material into orbit that eventually coalesced into the Moon. “This supports the theory that a planet collided with early Earth and the high-energy impact resulted in the formation of the Moon.”

By anchoring this lunar link to evidence found in Earth’s oldest surviving rocks, the study offers a rare bridge between planetary geology and cosmic origin theory.

First Appeared on

Source link