Scientists Stunned by 7,000-Year-Old Mummies With DNA From Nowhere on Earth

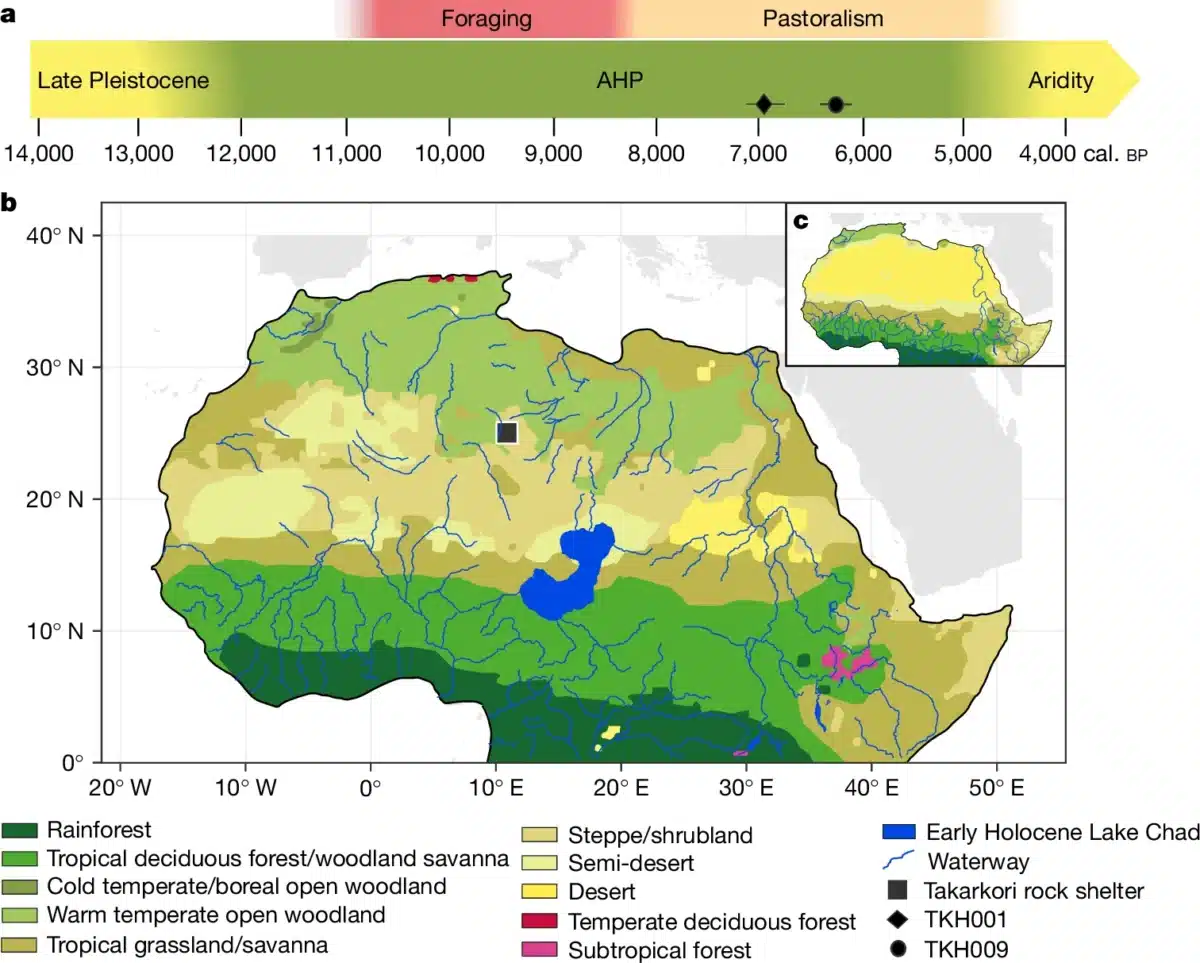

Two 7,000-year-old mummies, naturally preserved and buried in the Libyan Sahara, were discovered at the Takarkori rock shelter in southwestern Libya, where archaeologists recovered the remarkably well-preserved remains during excavations of early human burials.

According to a study published in the journal Nature, researchers believe the two mummies lived during the African Humid Period, a time when the Sahara was covered in rivers and grasslands rather than sand dunes.

A Ghost Population In The Heart Of The Sahara

Led by Nada Salem from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, the study analyzed DNA taken from the women’s teeth and leg bones. The results showed that they belonged to a previously unknown human lineage.

This genetic branch seems to have split from sub-Saharan African populations around 50,000 years ago, around the same time other modern humans were starting to leave Africa. As stated by the research, this lineage doesn’t appear to be directly connected to modern populations in the region.

“DNA extracted from two pastoralist women who were buried at the rock shelter around 7,000 years ago reveals that most of their ancestry can be traced to a previously unknown ancient North African genetic lineage,” said Louise Humphrey, a research leader at the Natural History Museum’s Centre for Human Evolution Research in London.

This supports earlier chemical studies suggesting that people buried at Takarkori lived and died locally, relying on nearby water sources and soils.

A Different Kind Of Neanderthal Legacy

One of the more puzzling aspects of the research is the tiny amount of Neanderthal DNA found in the mummies’ genomes, just 0.15 percent. That’s about a tenth of what’s typically found in people whose ancestors lived outside Africa, yet it’s still higher than in most ancient or modern sub-Saharan Africans.

This faint signal suggests that the Takarkori population may have had limited contact with groups linked to the Near East, perhaps during rare interactions along trade or migration routes. But there is no evidence of sustained or large-scale movement of people into this part of the Sahara. The low Neanderthal content positions this population much closer to human groups that remained within Africa than to those that settled in Eurasia.

How Herding Took Root Without Newcomers

Along with the mummies, archaeologists uncovered tools and animal remains tied to herding, including cattle, sheep, and goats. It’s clear the Takarkori women belonged to a community that had taken up pastoral life. Still, their DNA doesn’t show any signs of mixing with farming groups from the Levant or Southern Europe.

As reported by Earth.com report, the researchers think this points to cultural diffusion, meaning local people adopted new ideas and technologies without being overtaken by outside groups. The artifacts found at the site, like pottery and tools, also show gradual changes over time, suggesting slow, steady adaptation rather than major upheaval.

First Appeared on

Source link