NASA Just Uncovered a Hidden Rainbow Canyon in Utah, It’s Millions of Years Old

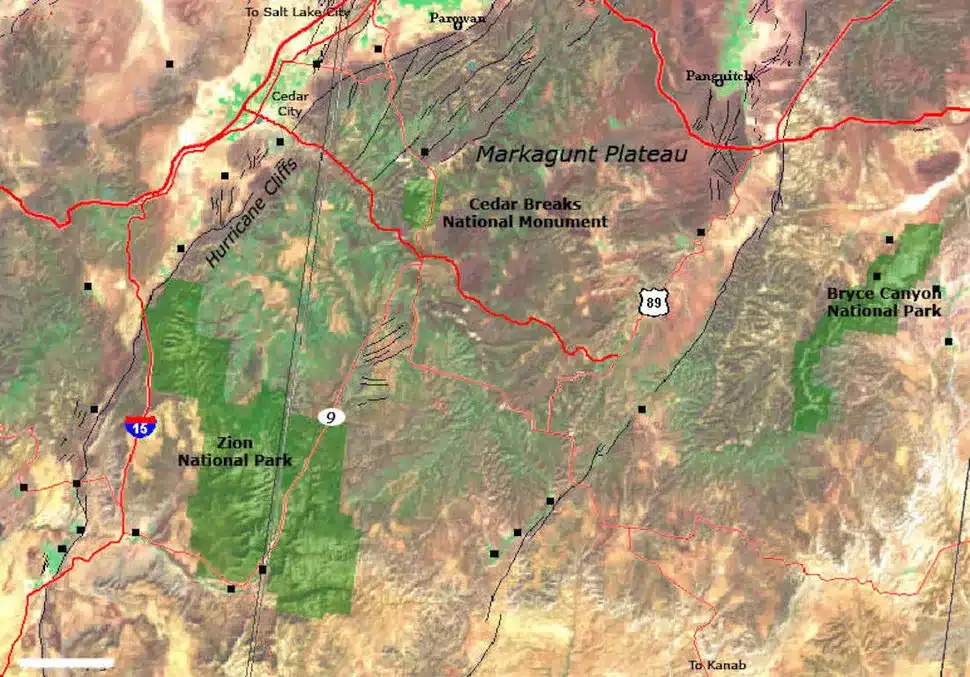

Towering above the Utah plateau at 10,000 feet, the cliffs and canyon walls of Cedar Breaks National Monument reveal a story etched in stone. Captured by NASA’s Landsat 9, the amphitheater’s bold colors and eroded patterns expose tens of millions of years of geological transformation.

From above, the semi-circular escarpment appears like an open wound in the Earth’s crust, carved by time, lifted by tectonics, and painted by ancient climates. The satellite image is a layered record of vanished lakes, fiery eruptions, and long-dead ecosystems, preserved in bands of orange, white, and gray.

The Rise and Retreat of Lake Claron

The colorful formations visible at Cedar Breaks trace their origins to a now-extinct body of water called Lake Claron, which once filled a large basin during the Eocene to Oligocene epochs, roughly 50 to 25 million years ago. Sediments settled on the lakebed over millennia, especially carbonate-rich muds, eventually solidifying into the limestone layers that dominate the cliffs today.

As water levels fluctuated and environmental conditions shifted, so too did the chemical makeup of the sediments. According to NASA Earth Observatory, during wetter phases, limited oxygen exposure caused iron-poor, pale-colored rocks to form. During dry spells, sediments rich in oxidized iron created vibrant red and orange layers. These chromatic shifts are still visible, offering a geologic record of ancient climate swings.

This natural palette, captured in both ground photography and Landsat imagery, helps researchers interpret the environmental past of the canyon without digging a single trench.

An Ancient Staircase to the Sky

Cedar Breaks occupies the uppermost tier of the Grand Staircase, an immense series of sedimentary rock layers stretching from southern Utah to the Grand Canyon. After the sedimentary layers formed, tectonic uplift slowly hoisted them to elevations exceeding 10,000 feet, making the monument a prominent geologic benchmark.

The amphitheater’s rim, now deeply incised by creeks like Ashdown Creek and its tributaries, reveals the force of erosion over time.

“The high elevation influences everything from the weather to the plants and animals that live there. Winters are long, cold, and snowy, with nearby Brian Head seeing 30 feet (10 meters) of snowfall each year on average,” said the report.

Despite these severe conditions, bristlecone pines cling to the exposed limestone rim. These gnarled trees, some over 1,700 years old, have adapted to the cold, dry environment, growing slowly and resisting decay through the density of their wood. Their resilience has made them icons of longevity in a place where little else takes root.

Echoes of Volcanic Fire

While water and sediment laid the groundwork for Cedar Breaks, volcanic activity left its mark more recently. Between 5 million and 10,000 years ago, volcanoes on the Markagunt Plateau erupted, leaving behind dark basaltic flows and tuff deposits that now flank parts of canyon-like amphitheater.

As stated by the U.S. Space Agency, these remnants are visible east of the monument, where pyroclastic flows from explosive eruptions once blanketed the area in ash and molten rock. Today, these layers remain around the summit of Brian Head, which has since transformed into a ski resort.

First Appeared on

Source link