Boston researchers identify at-risk areas

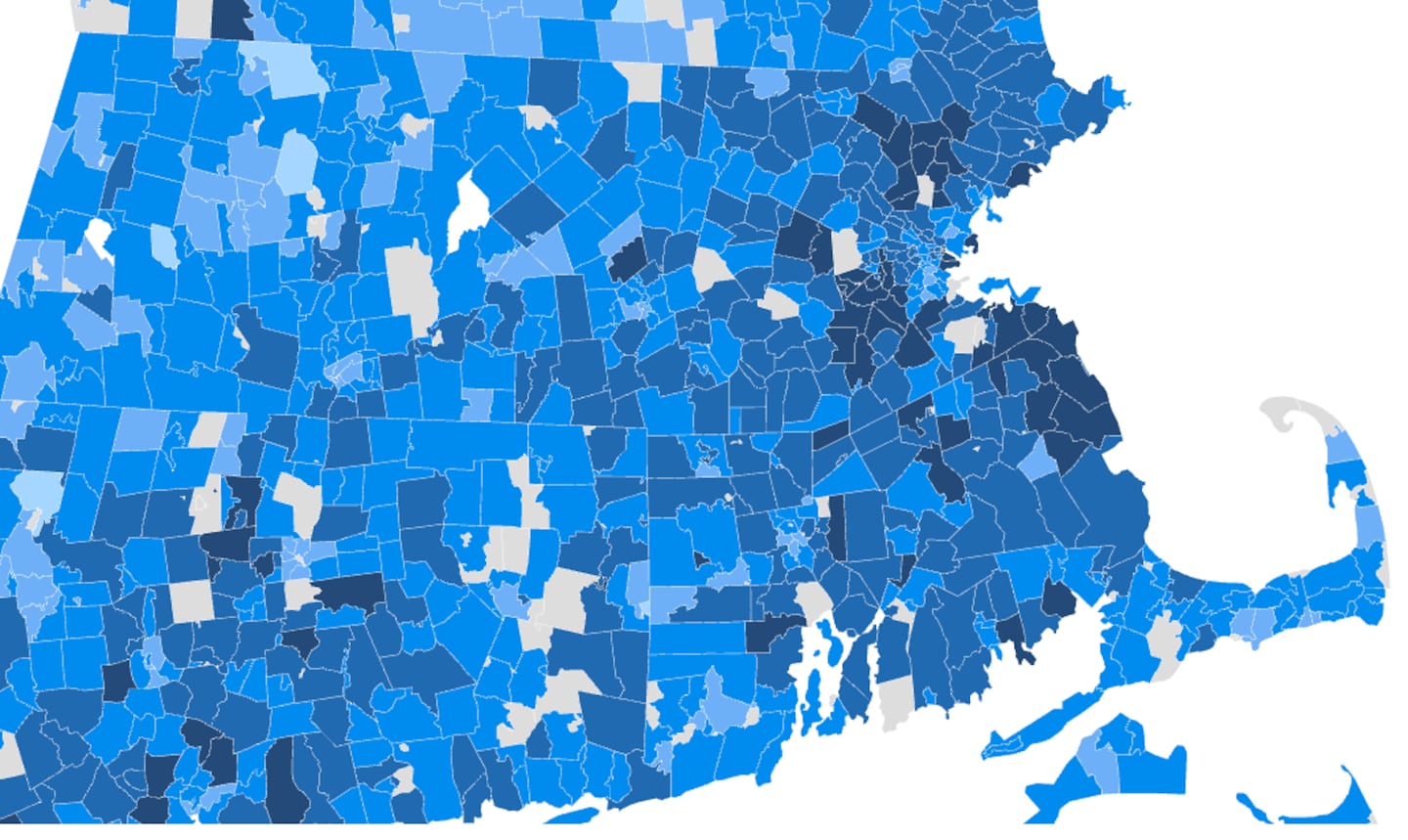

The Commonwealth has ZIP codes that range from very low risk for a measles outbreak, such as Winthrop’s 02152, to very high risk, such as Middlefield’s 01243 and Conway’s 01341, based on the percentage of children younger than 5 who have had at least one shot of measles, mumps, and rubella vaccine.

Compared to other New England states such as New Hampshire and Vermont, Massachusetts has comparatively fewer high-risk ZIP codes.

“Outbreaks are much more likely to happen where there is low vaccination,” said Dr. Ben Rader, scientific director of Boston Children’s Hospital’s innovation group, who coauthored the paper with Brownstein.

In their study, the researchers sought to capture children who are often missing from official reporting systems, such as those who are homeschooled, uninsured, or too young to attend kindergarten.

For that reason, their estimates for the number of kids vaccinated for measles are lower than those of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Brownstein and Rader started this work while researching vaccine hesitancy during the COVID-19 pandemic. They noticed that skepticism surrounding the COVID-19 vaccine seemed to spill over into routine childhood immunization, including the measles, mumps, and rubella, or MMR, shot.

To gather their data, the researchers used an online surveillance platform called Outbreaks Near Me, where parents voluntarily reported whether their children under 5 had received at least one dose of the MMR vaccine. They then applied a statistical method that uses limited survey data and population information to estimate what’s happening in a community, and a geospatial AI tool developed by Google to estimate vaccination rate down to the ZIP code level.

“Places that we found had severe pockets of under-vaccination ultimately became sources of major outbreaks in the US, like in West Texas and New Mexico,” Brownstein said. “But even more concerning is that it will likely reflect where we’re going to see future outbreaks in the coming years.”

Dr. David Hamer, professor of global health and medicine at Boston University, said Massachusetts remains relatively protected except for a few areas.

However, New England’s interconnectedness complicates risk. Travel between states increases the chance that measles from higher-risk areas could spread.

“It just increases our vulnerability for those areas in our state in particular that might have low vaccination rates,” said Dr. Nahid Bhadelia, an infectious disease physician and founding director of Boston University Center on emerging infectious diseases.

Bhadelia noted that parts of Western Massachusetts are beginning to show lower vaccination coverage.

“The concern for a state like Massachusetts that still maintains a pretty high overall vaccination is when you get these coalescing pockets of lower immunity,” she said.

Hamer said measles is one of the most contagious viruses known, requiring population-wide vaccination rates of roughly 93 to 95 percent to maintain herd immunity.

“Vaccination, of course, is about protecting yourself and your families, but it’s also about your community,” Brownstein said.

Bhadelia said that losing measles elimination status would signal more than just a symbolic failure.

“It really gives you a state of the nation in terms of our public health and our public health readiness and preparedness,” she said. “It’s reputational, but it also is saying something about disease burden within the country.”

A panel of international experts will review the US’s measles elimination status later this year.

She said rapid case identification, contact tracing, and public education will be essential to prevent outbreaks.

“The best we can do is continue to make sure that children are getting their first dose of MMR, and that they’re getting their second dose at the appropriate age,” Hamer said.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends children receive their first dose between the ages of 12 and 15 months and the second dose between ages 4 and 6.

Despite growing risks nationwide, Massachusetts’ strong public health infrastructure remains a critical safeguard.

“We’re great, but we’re not perfect,” Brownstein said.

Aayushi Datta can be reached at [email protected].

First Appeared on

Source link