New Alzheimer Discovery Reveals a Hidden ‘Erase’ Switch in the Brain

Scientists have uncovered a potential mechanism behind memory loss in Alzheimer’s that involves neurons pruning their own synapses, not being passively destroyed. The process appears to be triggered by a single receptor that responds to both amyloid beta and inflammatory molecules, suggesting these two longstanding culprits might actually work through the same destructive pathway.

This discovery reframes how Alzheimer’s disease might be causing damage, and potentially how it should be treated. Researchers now believe that stopping memory loss may depend not on breaking up amyloid plaques, as most current drugs attempt, but on protecting the synaptic connections themselves from being erased.

A Unifying Explanation for Memory Loss

Alzheimer’s disease has long been linked to various biological threats: amyloid beta plaques, tau tangles, and brain inflammation. Each seemed to independently play a role in damaging neurons. But now, a team led by Carla Shatz, professor of biology and neurobiology at Stanford, has identified a shared receptor (LilrB2) that appears to act as the common target of both amyloid beta and inflammatory proteins. As reported by Stanford’s Wu Tsai Neurosciences Institute, the finding offers a way to connect two major Alzheimer’s theories through a single molecular mechanism.

The key lies in synapse pruning, a process typically associated with brain development, where unnecessary synapses are eliminated to fine-tune neural circuits. In adult brains, this process is supposed to slow down, but in Alzheimer’s, it seems to go haywire. The receptor LilrB2 tells neurons when to remove synapses, and when hijacked by amyloid or inflammation-related proteins, it appears to initiate excessive synaptic loss.

Amyloid and Inflammation Converge on the Same Receptor

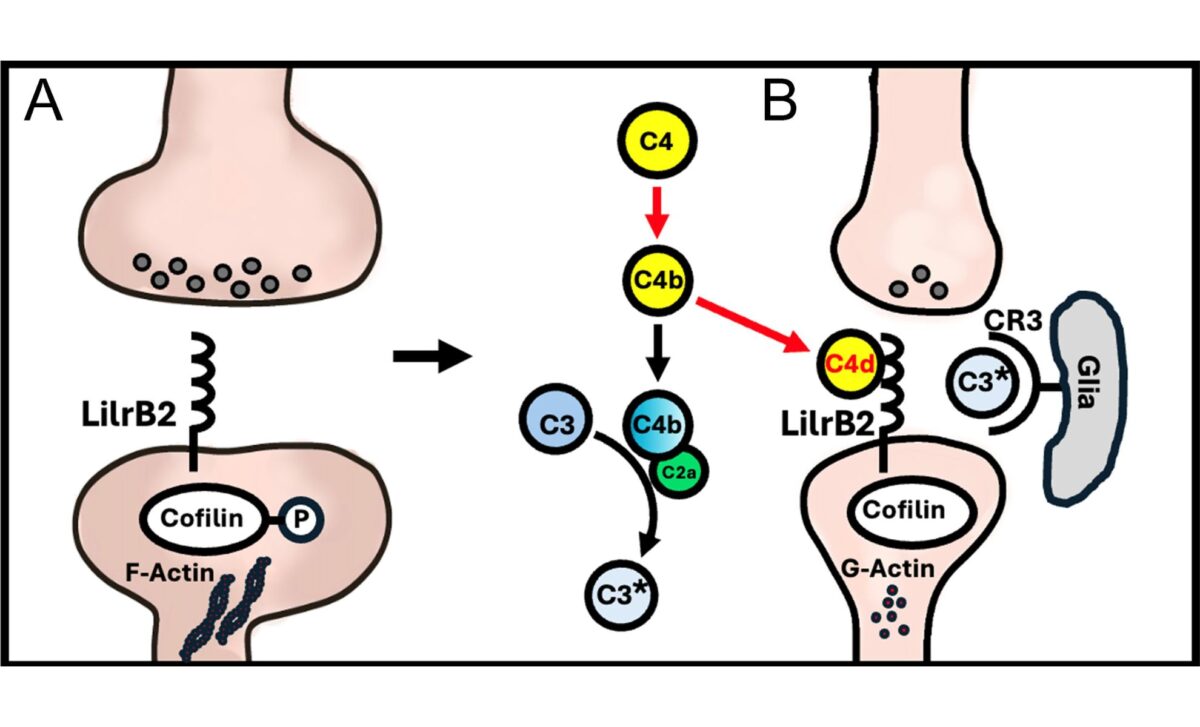

Back in 2013, Shatz’s team showed that amyloid beta binds directly to LilrB2, triggering neurons to dismantle their own connections. The new study deepens this connection by showing that a fragment of a complement protein, called C4d, also binds to this receptor with high affinity. According to findings published in PNAS, both amyloid beta and C4d may use LilrB2 as a common entry point to induce memory-related damage.

Testing this hypothesis, scientists injected C4d into the brains of healthy mice. The result was dramatic: synapses were stripped from neurons, replicating the kind of damage seen in Alzheimer’s. “Lo and behold, it stripped synapses off neurons,” said Shatz. This wasn’t a passive process, it was triggered by neurons themselves responding to signals via LilrB2.

What’s particularly surprising is that C4d had previously been considered biologically irrelevant. But this study reveals it plays a direct role in memory loss by actively engaging the same receptor as amyloid beta, reinforcing the theory that both pathologies share a single destructive signaling route.

Neurons Take the Lead in Self-Destruction

The traditional view has been that immune cells, especially microglia, are the main actors in synapse loss during neurodegeneration. But these findings flip that narrative: neurons are not bystanders, according to Shatz. They receive external cues and then make the choice to prune their own synapses, a striking demonstration of cell-autonomous action.

This was made evident in experiments using PirB knockout mice, PirB being the mouse equivalent of human LilrB2. When C4d was introduced into these genetically altered mice, no synapse loss occurred, unlike in normal mice. This confirmed that the receptor was necessary for the observed pruning effect.

Moreover, data from human brain samples analyzed using high-resolution array tomography showed that LilrB2 and C4d both localize at excitatory synapses, the very junctions responsible for learning and memory. In Alzheimer’s brains, these molecules were often found alongside amyloid beta, especially near plaques, further linking the trio at the site of damage.

Current Treatments May Be Missing the Mark

Most FDA-approved Alzheimer’s treatments target amyloid plaques in the brain. But their effectiveness has been limited, and some, like lecanemab, have been associated with serious side effects, including brain bleeding and swelling. “Busting up amyloid plaques hasn’t worked that well,” said Shatz. “And even if they worked well, you’re only going to solve part of the problem.”

Instead, this new research suggests that directly protecting synapses from LilrB2 signaling could be a more promising direction. Amyloid beta and inflammation may just be triggers, while LilrB2 is the actual executioner, and possibly the better target for intervention.

As inflammation and amyloid both increase with age and Alzheimer’s progression, understanding their convergence on this receptor may open doors to a new class of treatments aimed not at the plaques themselves, but at preserving the memory pathways they threaten to erase.

First Appeared on

Source link