20,000-Year-Old Tools Found in the U.S. Rewrite the Origins of the First Americans

New archaeological evidence is rewriting the early history of North America. A fresh look at ancient stone tools suggests that the first humans may have arrived far earlier—and traveled far differently—than once believed. Rather than trudging across frozen tundra, they may have hugged the Pacific coastline in boats. These insights, recently published in Science Advances, connect North America’s earliest settlers to a wider prehistoric world.

A Coastal Route Across The Pacific: Rethinking The First Migration

For decades, the prevailing theory held that the First Americans migrated from Siberia to Alaska across the now-vanished Beringia land bridge some 13,000 years ago. But new findings suggest a more complex narrative. An international team of archaeologists has analyzed a series of advanced stone tools found at multiple North American sites—tools strikingly similar to those unearthed in Hokkaido, Japan, dating back over 20,000 years.

This discovery, detailed in the peer-reviewed journal Science Advances, supports the emerging theory that early humans may have traveled by sea along the Pacific Rim, possibly using small watercraft. This theory aligns with the apparent absence of early tools in Alaska and the Yukon, and their abundance farther south—in Idaho, Pennsylvania, Texas, and Virginia.

“These weren’t just isolated hunter-gatherers,” said Loren Davis, professor of anthropology at Oregon State University.

“This study puts the First Americans back into the global story of the Paleolithic – not as outliers – but as participants in a shared technological legacy.”

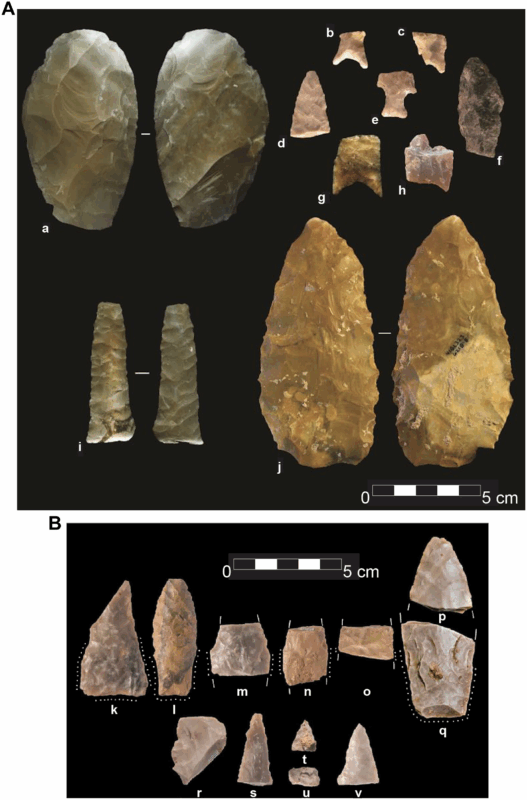

Their stone tools, including bifaces—finely crafted weapons honed on both sides—demonstrate a level of skill and design that links them directly to Paleolithic cultures in Northeast Asia. As Davis notes,

“This marks a paradigm shift. For the first time, we can say the First Americans belonged to a broader Paleolithic world – one that connects North America to Northeast Asia.”

American Upper Paleolithic: A Cultural Thread From Asia

Archaeologists are now referring to this wave of toolmakers as part of the American Upper Paleolithic, a term that frames them not only by their location or era, but by their shared material culture. The tools recovered reflect more than functionality—they carry the fingerprints of a migrating knowledge system.

In both form and craftsmanship, they mirror technologies from Paleolithic Japan and Siberia. This suggests that the migration into the Americas was not just a physical journey, but a cultural one, marked by continuity in knowledge and shared ways of surviving in harsh environments.

As Davis explains, “This system serves as the technological fingerprint linking the American Upper Paleolithic to its roots in Northeast Asia.” Genetic research bolsters this claim, tracing the ancestry of many Indigenous Peoples in North America to East Asian and Northern Eurasian populations.

These findings challenge the idea that the Americas were a cultural island in the Ice Age world. Instead, they portray the early settlers as part of a dynamic and interconnected human network, spanning continents. “We can now explain not only that the First Americans came from Northeast Asia, but also how they traveled, what they carried, and what ideas they brought with them,” said Davis.

Buried Evidence And Lost Coastlines: Why We’re Only Discovering This Now

The delayed recognition of this migration path stems largely from the nature of the landscape itself. As the last Ice Age ended, melting glaciers triggered a dramatic rise in sea levels, likely submerging many of the original coastal settlements used by these early migrants.

Archaeological evidence from these submerged sites is now lost or deeply buried beneath the Pacific. The stone tools recovered inland may be the last visible traces of a broader network of coastal activity that once extended along what is now the West Coast of the United States.

This helps explain the southward distribution of the earliest tools—far from where the Beringia land bridge once connected Alaska to Asia. It also reframes how scientists are approaching early American history, moving beyond land-based migration models.

“It’s a powerful reminder that migration, innovation, and cultural sharing have always been part of what it means to be human,” Davis reflected. The implications of this study extend beyond archaeology—they touch on how we define belonging, how we tell the story of migration, and how interconnected the ancient world truly was.

First Appeared on

Source link