500-Million-Year-Old Trilobite Fossils With Soft Tissues So Intact, They’re Blowing Paleontologists’ Minds

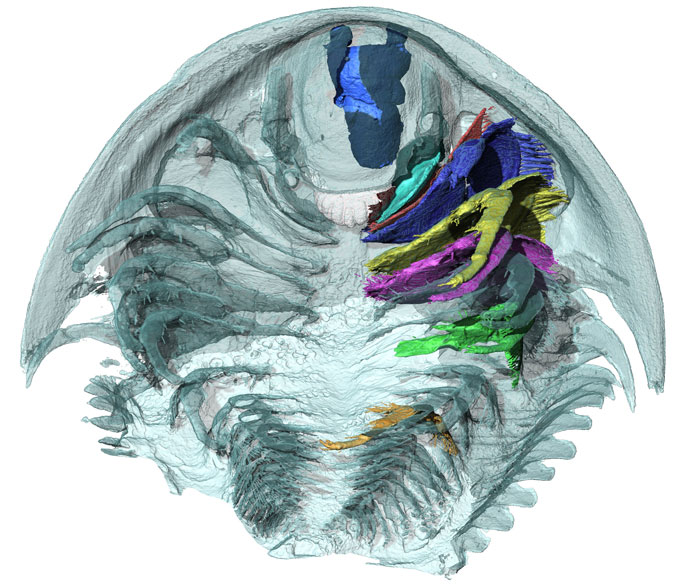

Buried beneath layers of volcanic ash for over half a billion years, a set of newly unearthed trilobite fossils from Morocco is reshaping the scientific understanding of one of Earth’s earliest and most prolific arthropods. Preserved with extraordinary detail, these fossils reveal for the first time in three dimensions the soft tissues of trilobites—including their antennae, legs, and digestive tracts.

Published in the journal Science, the find marks a rare paleontological moment: the ability to see how these marine animals truly functioned—beyond the exoskeletal impressions that have dominated the fossil record for centuries. The visual clarity of these specimens confirms long-suspected biological mechanisms and introduces new questions about why trilobites thrived for 270 million years—and why they ultimately disappeared.

The fossils emerged from the Atlas Mountains in a region not typically known for yielding soft-tissue preservation. The fine detail was made possible by a specific and violent geological event: a volcanic eruption that led to rapid mineralization in the ocean, capturing the trilobites mid-movement, before time and biology could erase their softer structures.

How Volcanic Ash Turned to a Fossilizing Force

The team behind the discovery, led by paleontologist John Paterson of the University of New England in Australia, emphasized that the level of preservation is unprecedented in trilobite research. Not only were the fossils lifelike, they captured parts of the body rarely—if ever—seen intact.

“These trilobite fossils represent the most complete specimens found to date, not only preserving the hard exoskeleton but also the soft parts in 3-D, such as the antennae, walking legs and the digestive system,” Paterson told Science News.

So how were these fragile biological details preserved for more than half a billion years?

Geologist Robert Gaines, of Pomona College and a co-author of the study, explains that the process began with a volcanic explosion, which unleashed superheated ash into nearby coastal waters. That ash dissolved and then re-mineralized, effectively entombing the trilobites in hours or days—a process far faster than typical sedimentary fossilization.

“The key step in this process,” Gaines told Science News, “is that the ash hit water before hardening around the trilobites; without the cooling effects of ocean water, the hot ash would have burned the trilobites away.”

He noted striking similarities to other exceptionally preserved Cambrian fossils, such as Aegirocassis, where the same mineralization process appears to have operated more than 20 million years earlier.

The result is a type of preservation rarely seen outside of amber or deep permafrost, and almost unheard of in marine fossils—particularly those this ancient.

Trilobites Fed With Their Legs—Literally

These 3D reconstructions are not just anatomical trophies—they provide clear validation of how trilobites fed, something that had remained speculative for decades due to the lack of soft-tissue data.

The fossils reveal that trilobites used multiple pairs of identical limbs, stretching from head to tail, to process food along a central groove toward a tiny, unspecialized mouth.

“Food processing took place along the entire length of the animal,” paleontologist Nigel Hughes of the University of California, Riverside told Science News. Though he wasn’t involved in the study, Hughes emphasized the significance of the clarity: “It provides a level of preservation detail that unequivocally confirms a number of conjectures made based on less well-preserved material.”

This feeding strategy contrasts sharply with modern arthropods like crustaceans, which evolved specialized appendages for tasks like swimming, digging, or self-defense. Trilobites, it appears, stuck with a basic limb design across hundreds of millions of years.

The researchers suggest that this lack of limb specialization—an evolutionary conservatism—may have left trilobites vulnerable in later, more competitive ecosystems, contributing to their eventual extinction at the end of the Paleozoic era.

Challenging Fossil Norms—And Expanding the Search

Beyond the biology, the find is forcing scientists to rethink where exceptional fossils can be found. Traditionally, paleontologists focus their search on sedimentary rock, which is more likely to preserve organisms gently over time.

But these trilobites were found in volcaniclastic deposits, a rock type formed from ash and debris from volcanic eruptions—historically viewed as too chaotic and hot for fossil preservation.

“Geology and paleontology students at universities are often told that fossils are found only in sedimentary rocks,” Paterson said in the Science News article. “But our new study completely contradicts that notion.”

The researchers hope the discovery will prompt a re-evaluation of volcanic environments as potential fossil repositories. Given the frequency of volcanic activity in Earth’s deep past, other such discoveries may be waiting in overlooked strata around the world.

First Appeared on

Source link