Soft robots can now be 3D printed to move exactly as designed

Harvard engineers have developed a new 3D printing technique that allows soft robots to bend, twist, and change shape in predictable ways when inflated.

The approach embeds shape-morphing behavior directly into the printed structure, removing much of the guesswork that has long plagued soft robotics design.

Soft robots, typically made from flexible and biocompatible materials, are increasingly attractive for applications ranging from surgery to industrial handling. But controlling how these machines move has remained difficult.

Traditional fabrication relies on molds, layered casting, and surface-patterned air channels, making customization slow and complex.

The new method replaces those steps with a single 3D printing process that creates long, flexible filaments containing precisely positioned hollow channels.

When air is pumped into these channels, the structure bends in specific, preprogrammed directions.

The work was led by graduate student Jackson Wilt and former postdoctoral researcher Natalie Larson in the lab of Jennifer Lewis at Harvard’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences.

The team combined several existing printing techniques developed in the Lewis lab into a single fabrication strategy that enables rapid design changes without molds.

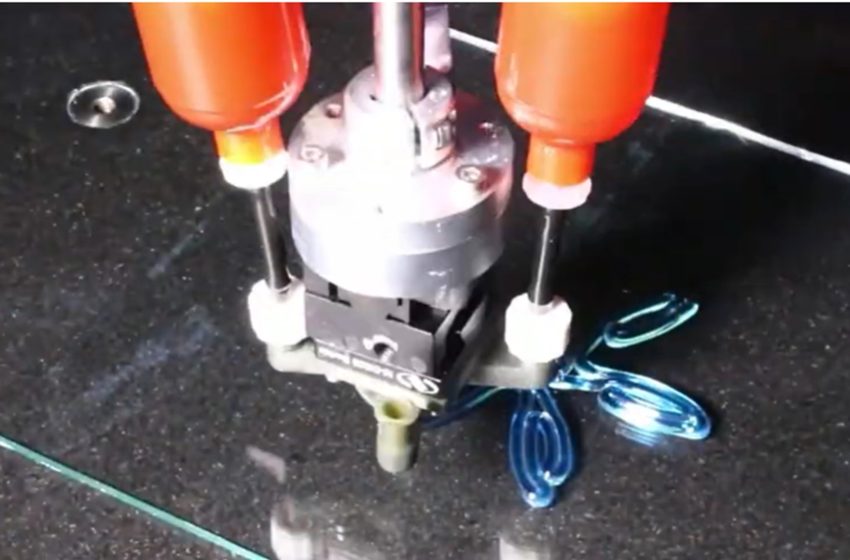

The key is a process called rotational multimaterial 3D printing, which uses a single nozzle to print multiple materials at once.

By rotating the nozzle during printing, the researchers can control where different materials are placed inside each filament.

Printing motion into matter

Using this approach, the team printed filaments with a tough polyurethane outer shell and a removable inner core made from a gel-like polymer commonly found in hair products.

By adjusting the nozzle rotation speed, flow rate, and geometry, the researchers controlled the orientation, size, and shape of the inner channel with high precision.

Once the outer shell solidified, the inner gel was washed away, leaving behind hollow channels. These channels act as built-in pneumatic pathways that drive motion when pressurized.

Depending on how the channels are positioned, the filament can bend, twist, or contract in predictable ways.

“We use two materials from a single outlet, which can be rotated to program the direction the robot bends when inflated,” Wilt said.

“Our goals are aligned with creating soft, bio-inspired robots for various applications.”

Unlike conventional soft robotics manufacturing, the method eliminates the need for casting, sealing, and multi-step assembly. Designs can be modified quickly by changing print parameters rather than rebuilding molds.

From flowers to grippers

To demonstrate the technique, the researchers printed a spiral, flower-like actuator in one continuous path that opens and curls when inflated.

They also created a hand-shaped gripper with five digits and defined knuckle joints, showing how complex, articulated motion can be achieved in a single print.

Because the structures are printed from flexible and potentially biocompatible materials, the technology could be useful in areas such as surgical robotics, assistive devices, and human-machine interfaces.

The ability to rapidly customize motion could also benefit soft manufacturing tools designed to handle delicate objects.

Larson, now an assistant professor at Stanford University, and Wilt say the technique offers a new way to think about soft robot design by embedding function directly into printed matter rather than adding it later.

The study was published in Advanced Materials.

First Appeared on

Source link