Lunar mysteries: Artemis moon missions could answer scientists’ big questions

When NASA’s Artemis II mission embarks on a 10-day journey around the moon, the crew may glimpse features on the lunar surface that no other human has seen with the naked eye.

As the astronauts fly by the mysterious lunar far side, which always faces away from Earth, they will view a part of the moon that Apollo astronauts were unable to see due to the orbits of their capsules.

The upcoming historic mission, expected to lift off as soon as early March, will mark the first time humans have ventured to the moon’s vicinity in more than 50 years — and kick-start a new wave of lunar exploration that could answer enduring questions about Earth’s natural satellite.

“We’ve been looking at the moon throughout human history, and the moon has been visited by astronauts and a number of robotic missions,” said Jeff Andrews-Hanna, a professor in the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona. “Yet there’s still so many things we don’t understand about the moon on a very first order level.”

Crucial samples collected during the Apollo missions in the late 1960s and early 1970s provided the foundation for our current understanding of the moon, he said. Lunar rocks and soil offered novel insights into the moon’s origin and composition, and more recent analysis of previously untouched Apollo samples, as well as samples retrieved by robotic missions, revealed the surprising discovery of water trapped in rocks thought to be bone-dry.

However, the Apollo missions ventured to similar sites near the lunar equator on the moon’s near side, where the terrain was flat and astronauts could remain within reach of communication satellites. As scientists have come to realize, the samples aren’t wholly representative of the wildly diverse moon, Andrews-Hanna said.

Exploring different lunar regions with the Artemis program could provide a more complete portrait of the landscape and its composition, and uncover clues on why the moon’s near and far sides differ, how much water the moon contains and how the silvery orb has evolved over time.

What’s more, studying the moon could shed light on lost chapters of Earth’s early history, and help to confirm or refute the prevailing theory that the moon formed from the impact of another celestial body colliding with our planet millions of years ago.

“I think of the moon as the eighth continent of Earth,” said Noah Petro, chief of NASA’s Planetary, Geology, Geophysics and Geochemistry Laboratory at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland. “When we study the moon, we’re actually really studying an extension of the Earth.”

And then there is the promise of the unexpected.

“We will have surprises,” said Petro, who also leads the science team for the Artemis III mission, which will aim to return astronauts to the lunar surface in 2028. “That’s why we explore. If we knew what we would find, we wouldn’t have to go.”

Anytime a spacecraft ventures to the surface of a planet or an asteroid, the best thing it can do is bring back a souvenir to Earth, said Barbara Cohen, project scientist for the Artemis IV mission, another planned lunar landing later this decade.

“Even though we weren’t there on the planet when that rock formed, the rock records the history of what was happening at the time, so they’re really, really important for a lot of different science endeavors,” Cohen said.

After the Apollo samples were returned to Earth and analyzed, textbooks were updated with a wealth of new information about the moon.

“I think it’s important to recognize how little we knew about the moon before the Apollo program,” said Paul Hayne, associate professor in the department of astrophysical and planetary sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics.

Before the moon landings, scientists debated whether the satellite originated elsewhere in the solar system before our planet’s gravitational field captured it, or did it form alongside Earth or even spin off from the rapidly rotating Earth like a blob, said Carolyn Crow, assistant professor in the department of geological sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder.

But the Apollo samples pointed to a novel theory about how Earth acquired such a big moon, Crow said.

Within the samples was anorthosite, a type of igneous rock. Anorthosite is rarely uncovered on Earth in isolation, usually existing as a mineral component of other rocks. But the white rock was prevalent on the near side of the moon, suggesting that the right conditions existed for it to form, Crow said.

“What you need is a really big magma pond that slowly crystallizes and all of the anorthosite will float up to the top of the pond if it’s cooling slowly enough,” Crow said.

The presence of anorthosite on the moon suggested that the entire orb was once a magma ocean, or completely molten. Additionally, isotopes, essentially chemical fingerprints for planetary bodies, found in Apollo rock samples matched isotopes in Earth’s mantle, suggesting they formed at the same time.

Taken together, these insights helped scientists arrive at the current prevailing theory that a Mars-size object smashed into Earth, ejecting a blob of molten material from our planet that became the moon.

“The Earth would not be the planet it is today had it not been for the moon-forming impact,” Andrews-Hanna said. “Because of the existence of the moon, the Earth and our climate are much more stable, and that has really been critical to the development of life. There’s no question that without a moon stabilizing the Earth, humans would not have been able to evolve.”

The Apollo missions revealed elements of the lunar near side that had never been observed.

But data from orbiters showed that the far side is completely different, leading to questions that have loomed large for scientists since the missions ended.

“The moon is lopsided in nearly every respect, and we don’t know why,” Andrews-Hanna said. “This global asymmetry has affected every aspect of the moon’s evolution and remains one of the biggest mysteries in lunar science.”

The near side has a thin crust, low topography and KREEP, a geochemical component rich in heat-producing radioactive elements. The material, left over from when the moon’s magma ocean solidified, is a combination of potassium, rare Earth elements and phosphorus found in lunar rocks.

The Apollo landing sites were also clustered around lunar maria, or dark patches where ancient lava once flowed, which give the appearance of the “man in the moon,” Hayne said.

Alternatively, the far side has a thick crust, higher elevations and far fewer signs of previous volcanic activity, Andrews-Hanna said.

The moon may appear like a dead rock from Earth’s vantage point, but instruments placed by Apollo astronauts showed that it is seismically active, with moonquakes that occur as the celestial body cools over time.

“One of the big questions that we’d like to answer is what’s going on inside the moon,” Hayne said.

Intriguingly, the lunar surface is littered with craters that record the chaotic early days of the solar system when planets and asteroids were smashing into one another. Much of that record has been wiped from Earth’s surface due to erosion and other natural processes, but the moon remains a perfect time capsule.

“Understanding the history of the early impact bombardment of the moon and of the Earth is really key for understanding the origin of life on Earth,” Andrews-Hanna said. “All evidence seems to indicate that as soon as the rate of impacts dropped down low enough for the surface to be stable, life arose.”

The Apollo 14 and 15 missions ventured near Mare Imbrium, one of the largest craters in the solar system, and collected ejecta, or material blasted out by the initial impact and spread across much of the lunar near side.

Imbrium is believed to be one of the youngest craters on the moon, forming 3.85 billion to 3.92 billion years ago.

“To be able to address what the moon was like before Imbrium, you have to go somewhere that wasn’t painted with this big brush, which means something like the south pole or the far side,” Cohen said.

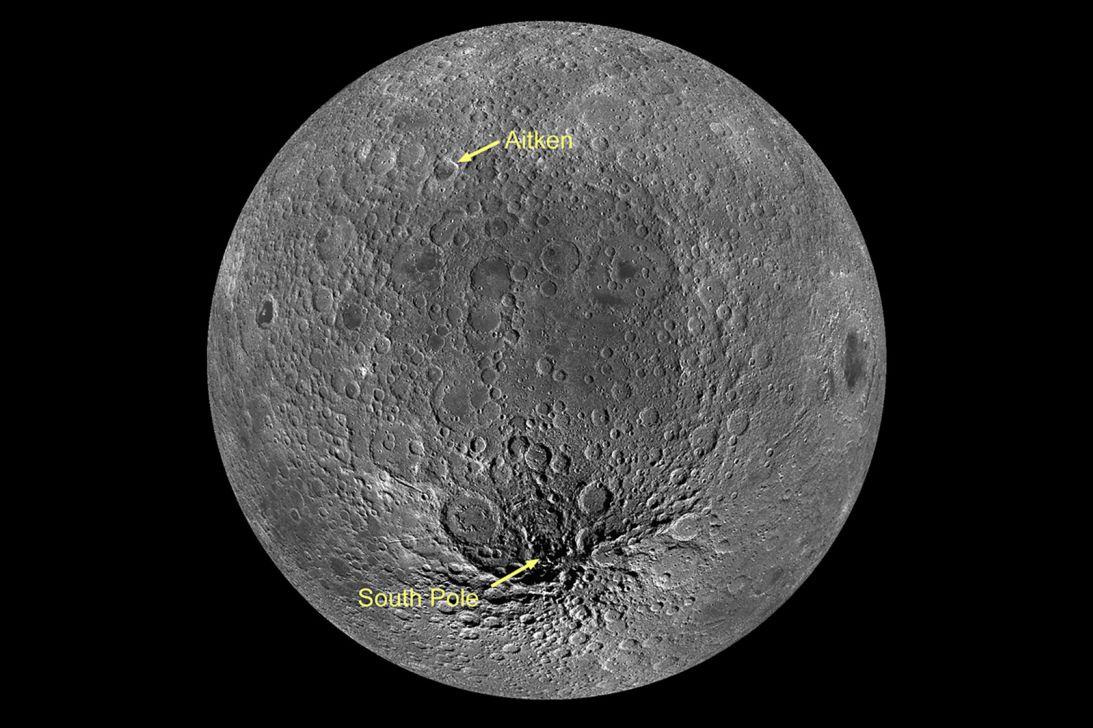

Now, scientists want to determine when other impact craters formed on the moon — especially the South Pole-Aitken basin. Spanning nearly a quarter of the lunar surface, the crater, which sits on the far side of the moon, is the largest with a diameter measuring roughly 1,550 miles (2,500 kilometers). It is more than 5 miles (8 kilometers) deep.

Such a giant impact could have been responsible for giving the moon its lopsided nature. The South Pole-Aitken basin is believed to be the oldest crater on the moon, but its exact age is unknown, making it a prime target for future Artemis missions.

“Understanding its age is like finding this Rosetta stone of the early history of the solar system,” Petro said.

A moon landing isn’t planned until Artemis III, during which two astronauts will venture to the lunar south pole region. The mission is currently expected to launch by 2028, according to NASA.

But observations from the forthcoming Artemis II could inform the selection of future landing sites.

During Artemis II, as the Orion capsule that houses the astronauts makes its closest approach of the moon, the orb will appear the size of a basketball when held at arm’s length, according to NASA.

Orion will fly 4,000 to 6,000 miles (6,437 to 9,656 kilometers) above the lunar surface, much higher than the Apollo command modules that flew around the moon from 70 miles (112 kilometers) above its surface or the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, a robotic mission circling the moon since 2009 that comes within 30 miles (48 kilometers) of its cratered face.

During the Artemis II mission, the entire disk of the moon will be on display, including normally shadowy areas near the lunar poles.

The Artemis II crew, which includes NASA astronauts Reid Wiseman, Victor Glover and Christina Koch, and Canadian Space Agency astronaut Jeremy Hansen, has undergone extensive geology training in lunar analogs on Earth such as Iceland.

During their three-hour flyover of the moon’s far side, the astronauts will capture images of impact craters and ancient lava flows as well as describe what they see to scientists at NASA’s Johnson Space Center who are prepared to offer guidance and analysis in real time.

“On Artemis II, the specific questions that we’re asking are really unique to what the human observer can do,” Petro said. “A well-trained pair of eyes is the greatest experiment we can send anywhere in the universe because it’s attached to their own curiosity.”

Depending on Artemis II’s trajectory, which will be determined based on its exact launch date, the crew may witness a previously shadowed region called the Orientale Basin. The crater, which is 600 miles (965 kilometers) wide, represents a key transition region between the near and far sides of the moon.

The crew might also spy distinct flashes of light as space rocks strike the moon — or dust floating above the edge of the moon, a mysterious phenomenon scientists have yet to understand fully.

Returning to the surface during Artemis III and Artemis IV, astronauts will capture observations, set up experiments and collect samples from their south pole landing site, the specifics of which remain to be determined.

Between Apollo and robotic missions to the moon, only 5% of the lunar surface has been sampled, Crow said.

Samples from the south pole, such as those containing material blasted out of the lunar interior more than 4 billion years ago, could shed light on an unknown chapter of the moon’s murky story, Andrews-Hanna said.

Seismometers, such as the ones placed on the moon’s near side during the Apollo era, will be left at the south pole to determine whether moonquakes can be detected on the far side. Tracking the passage of seismic waves as they move through the moon could also reveal more about its interior.

Other mysteries linger at the lunar south pole, such as how much ice is trapped deep within permanently shadowed regions of the moon.

“The holy grail, from my point of view, is how much ice is there and where did it come from,” Hayne said. “If we can get a sample, we could maybe find out where that water came from, and then, by extension, where Earth got its water.”

A freezer will be brought to the moon during the third planned lunar landing of the Artemis program, Artemis V, enabling the return of frozen samples to Earth, Cohen said.

“We’re really trying to go to these deep polar craters where we think water might be so that we can understand the history of water on the moon, which Apollo absolutely did not know anything about,” she said.

Artemis is often lauded as the moon to Mars program because technology and infrastructure developed for the longer-duration moon missions could lay the groundwork for eventually sending crewed missions to Mars.

It’s fitting, Petro said, because in a billion years, Mars will lose the last vestiges of its thin atmosphere and become more like the moon.

“I like to think of the set of three: Earth, moon and Mars,” Petro said. “And if we understand those three objects, we have a good understanding of how planets anywhere would work. And the moon is the best place to start making those discoveries.”

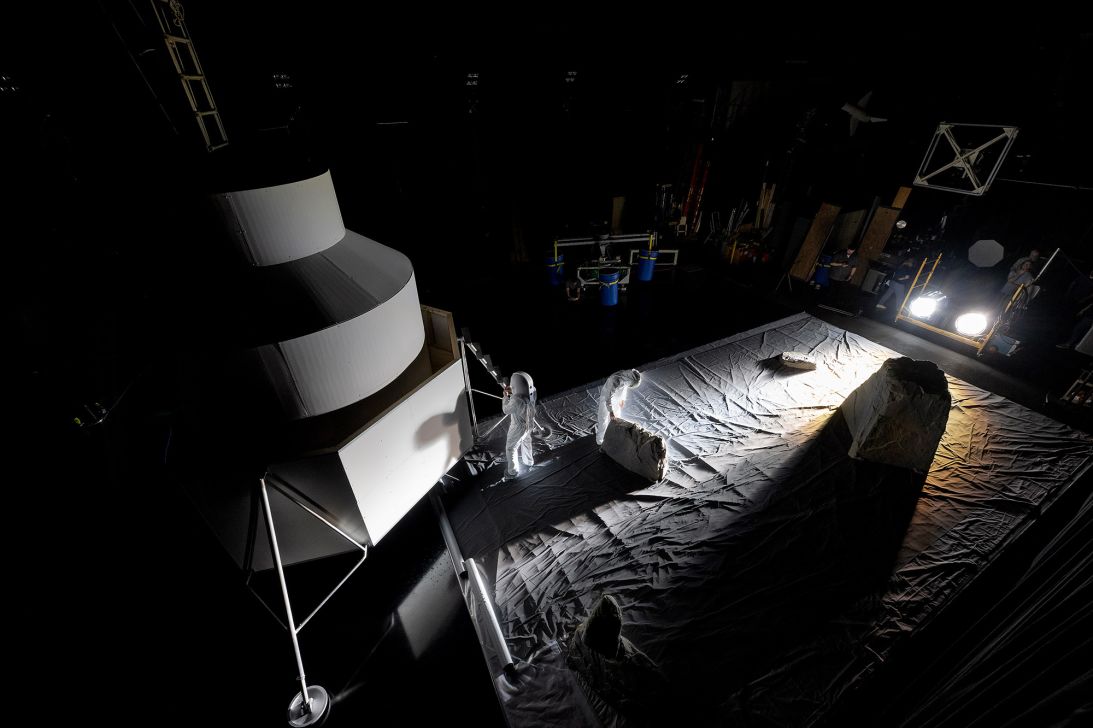

Petro’s love of the moon was sparked by his father, who was an electrical engineer in the development of the Apollo lunar module as well as the backpacks astronauts wore on the lunar surface, both of which helped keep crews alive in an incredibly hostile environment. His father shone a spotlight on lunar exploration for Petro, igniting his desire to help solve the moon’s biggest mysteries.

“The way we have explored the moon is diverse: landed missions, orbital missions, crewed missions,” Petro said. “We’re a long way from having a comprehensive picture of the moon, but we’re building the story.”

Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news on fascinating discoveries, scientific advancements and more.

First Appeared on

Source link