South Shore Residents Made Thousands Of Distress Calls To City Before Massive Federal Raid

SOUTH SHORE — Residents of a troubled South Shore apartment building made thousands of service and emergency calls to the city in the years before a massive federal immigration raid there made national headlines, according to records reviewed by Block Club.

The call logs, obtained through public records requests, detail issues from broken elevators and flooding to shootings and alleged drug activity that persisted at 7500 S. South Shore Drive, with residents at times saying their landlord was no help.

Overall, 500 calls to 311 were made about the building Oct. 1, 2021-Oct. 1, 2025, an average of about one complaint every three days, records show.

Another 2,630 calls were made to 911 involving the property Jan. 1, 2021-Oct. 1, 2025, an average of more than one emergency call a day for almost five years.

Federal agents targeted the building in a controversial Sept. 30 raid, the largest of Operation Midway Blitz. Hundreds of agents, some rappelling from helicopters, busted doors and zip-tied American citizens in the middle of the night, according to residents and witnesses. Federal officials said at least 37 people were arrested, claiming the building had been frequented by Venezuelan gang members.

Few residents remain inside the 130-unit building after the raid, and city officials have called to clear it out due to its dire conditions. At a foreclosure hearing involving the property last week, a county judge said she was told unresolved building issues may have led to the raid.

“The city was contacted, the Chicago police were contacted to come to this building, they refused. And that is when ICE got involved. That is what I was told,” Cook County Circuit Judge Debra Seaton said. “No way I can verify that.”

Many complaints to 311, including the ones below, were closed soon after they were made and labeled both “completed” and “active case,” according to the records reviewed by Block Club.

The “entire building is in disarray,” with violations including “everything under the sun,” according to 311 complaints from July 2 and 9.

“Living conditions in building is terrible, people are smoking crack in the hallway, bathroom ceiling is caving, bugs coming through wall, trash all through the hallway, drug dealing going on out of someone’s apartment,” according to a 311 complaint made Feb. 19, 2024.

“Caller says building is infested with rats … states people are living in the stairwell of building,” according to a 311 complaint from Aug. 3. “Entire building smells like mold and mildew.”

“Overcrowded with people, windows busted out, blinds torn up, directly across the street from a school,” according to a 311 complaint from Sept. 1.

A 311 complaint calling the building “vacant” and “open and dangerous to squatters” was made less than two weeks before the raid. Another complaint filed a day after the raid described its desperate situation, with the complainant calling the entire building “uninhabitable.”

“Anything and everything wrong is happening here,” the complaint reads. “The landlord will not address any of the most basic issues.”

The building’s owner, Wisconsin-based investor Trinity Flood, faces foreclosure after defaulting on loan payments for the building and two other South Shore properties she bought in 2020, according to court records. Block Club has not been able to reach her for comment.

The building’s property manager helps run a political action committee that gave campaign money this year to more than a dozen City Council members, among them Ald. Greg Mitchell (7th) whose ward includes the building, a Sun-Times investigation found.

The majority of 311 calls were referred to the city’s Department of Buildings. The property has failed its last 15 building inspections, according to city records.

Nefsa’Hyatt Brown, a building department spokesperson, said in a statement that a failed January inspection “warranted an escalation of our enforcement process,” leading to a February city lawsuit filed against Flood’s companies that alleged more than a dozen unresolved building code violations dating back to 2023.

But issues have continued while the lawsuit has been active.

The city’s concerns have included “armed occupants along with alleged criminal activity and shootings” and “property management’s inability to re-assert control over the building,” which prevented the city from “a full interior inspection of the property due to the security concerns,” Eduardo Martinez, a city attorney, wrote in an August email.

Flood and building management company, Strength in Management, had yet to confirm if it installed burglar bars on vacant units to help “remove unauthorized occupants,” Martinez said.

Two more scheduled inspections in August and September didn’t occur because of “ownership not being present to join the [Department of Buildings] inspectors,” Brown said.

“The conditions in the building were deplorable, which is why [the Department of Buildings] cited it for violations on multiple occasions in an effort to ensure accountability for the residents,” mayoral spokesman Cassio Mendoza said in a statement. “However, the Trump administration’s militarized raid of the building had nothing to do with its conditions or community safety.”

This year through Oct. 1, the property has been the subject of 45 calls to 911 for noise disturbances, 37 for emergency medical services, 32 for domestic disturbances, 27 related to burglary, 17 about a person with a gun and 15 regarding shots fired, according to records and a listing of event types from the Chicago Justice Project.

One call of shots fired was made June 22, the day Jose Javier Coronado-Meza is accused of fatally shooting 31-year-old Gregori Arias in one of the building’s apartments.

City inspectors were scheduled to come to the building the day after, but the inspection “was not completed due to police activity in the area,” Brown said. It was only after the raid that court-ordered inspections were completed.

The latest inspection, on Oct. 15, “showed that the property owners are working towards addressing the cited building code violations,” Brown said.

Samantha Stamps, a resident of the building for three years, told Block Club she has made about 10 calls to 311 and 911 during her time living there.

In one instance, a person snatched Stamps’ purse with her keys inside as she came home from work. She called management to have someone let her in her unit, but firefighters had to break into her apartment to let her in after no one from management showed, she said.

“They didn’t do s—,” Stamps said when asked about the landlord’s responsiveness to maintenance requests regarding pest infestations, broken elevators, broken locks and other issues in the building. “They [would say] they were going to do something, and they didn’t do it.”

At the foreclosure hearing last week, Seaton gave Strength in Management more time to clean up the building after she said the company made “a good-faith effort” on making improvements following the raid.

However, Stamps said conditions in the building are “still the same.” Other residents doubted Flood or management would have addressed the living conditions if not for the raid.

“They’re only doing all this stuff right now because they’re in the spotlight,” said Darren Hightower, a resident of two years. “If this hadn’t gotten national news attention, this building would still be in decline.”

Residents frequently called 311 about the building’s malfunctioning elevators, including a complaint in April that an older person who uses a wheelchair missed a doctor’s appointment after the elevators had been out of service for days.

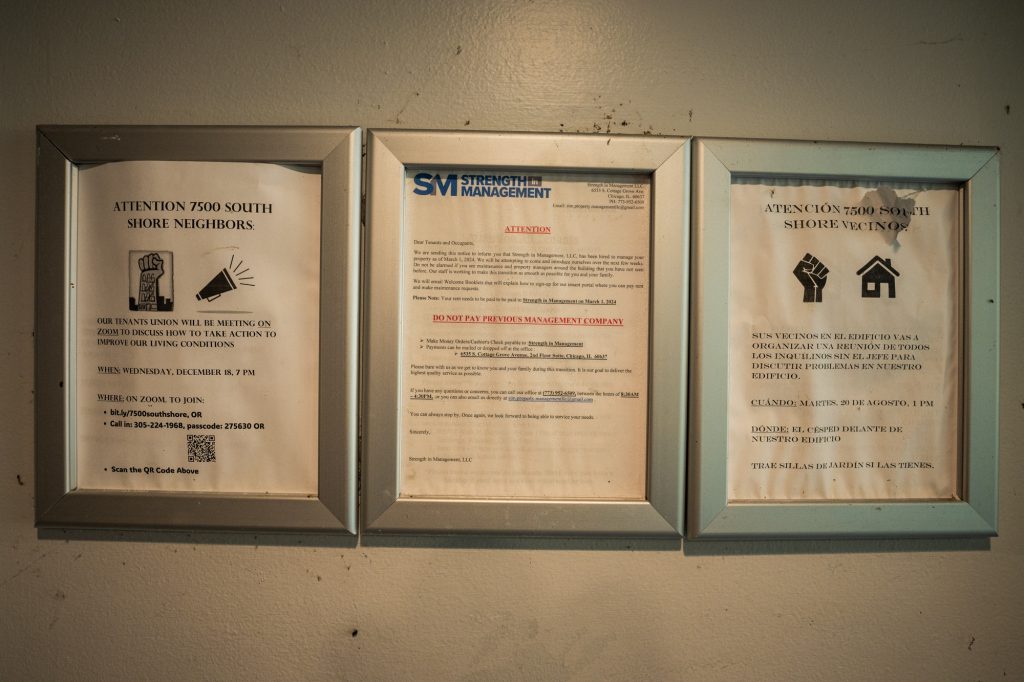

Jonah Karsh, a Metropolitan Tenants Organization employee who tried to unionize building residents, said the elevators had been breaking down to the point where a technician was “coming every week or two.”

“The city had no clear accountability mechanism to make the landlord feel the pressure” to replace the elevator, Karsh said.

“I have never advised someone not to call 311, but I think the systems that exist are completely inadequate to ensure compliance. And then you get a building that looks like 7500 South Shore.”

The unionizing effort failed after “it became clear” tenants would need to go public about issues at the building after Flood and management refused to work with them, Karsh said.

“They’re in an awful building to begin with, but it’s a place to stay when you don’t have another place to stay,” he said. “People were afraid of the consequences of any retaliation.”

Dispatchers received 15 emergency calls on Sept. 30, the day the feds raided the building. Several calls in the early morning — made as armed agents in camouflage stormed the building — reported fireworks, a person with a gun, a disturbance and other general concerns.

Five burglary-related calls were made in the hours following the raid. A resident told Block Club his apartment had been ransacked in the day after agents broke his door.

Though residents have told Block Club they believe the building is a hot spot for drug sales, records show only one such call was made so far this year, on July 30.

Police responded but labeled the call a “19-Boy” — a code for “nothing to see here.”

Listen to the Block Club Chicago podcast:

First Appeared on

Source link