The sperm black market where men donate via ‘natural insemination’

“I’m a 31-year-old ex-military, former semi-pro rugby player,” writes a Facebook user.

“6ft tall, dark brown hair, brown eyes,” offers another.

“I’m healthy, in good shape, go to the gym three times a week, and play sports regularly,” adds a third.

They sound like dating profiles, but these men are not looking for romance. They are offering their sperm to strangers on a Facebook group called Sperm Donors UK. With more than 17,500 members, it is one of dozens of online groups where women hoping to conceive, either alone or with a partner, can browse potential donors.

Scroll through and the tone can shift abruptly from benevolent to unsettling. Some men frame their offers as altruistic – “helping others achieve their dreams” – while others are blunter, advertising “free sperm” in exchange for intercourse. On the more “ethical” end of the spectrum, it still feels faintly grubby: a digital bazaar where biological parenthood is negotiated through chat threads and private messages.

For experts, this unregulated trade raises troubling questions. When done via official channels, sperm donation in the UK is a tightly regulated process, overseen by the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority (HFEA). At licensed clinics, donors must undergo extensive health checks, including screening for infectious diseases such as HIV and genetic conditions such as cystic fibrosis and sickle cell anaemia.

Vials of frozen donor sperm inside a liquid nitrogen tank at California Cryobank, one of the largest sperm banks in the world – Ted Soqui

Semen samples are analysed for quality and stored in quarantine for at least six months before being released for use, after the donor is re-tested to confirm they remain disease-free. Donors are also counselled about the legal and emotional implications of donation, since under UK law children conceived this way have the right, once they turn 18, to request identifying information about their donor. In return, donors receive a small allowance to cover expenses, but payment beyond this is prohibited.

For would-be parents, the official route is equally structured. Donor sperm can be accessed either through NHS-funded fertility treatment, for those who meet eligibility criteria, or by purchasing vials from a licensed clinic. Prices vary, but typically range between £900 and £1,300 per vial, with additional costs for storage, screening and insemination. Most clinics recommend purchasing multiple vials from the same donor to allow for future siblings.

While it may not be illegal, the HFEA warns that finding donors via Facebook and other social media groups, and buying sperm from them – without the medical screening, legal safeguards or psychological checks of licensed clinics – exposes participants to potential exploitation and risk.

There’s also the not insignificant issue of multiple untracked conceptions. In 2016, a man named Simon Watson appeared on the BBC’s Victoria Derbyshire programme claiming to have fathered as many as 800 children over 16 years of unregulated sperm donation, offering samples for £50 each via social media.

Although Watson presented his actions as selfless, fertility experts described it as “deeply disturbing” warning that such large numbers of genetically-related children raise the risk of accidental incest in later life, as well as the emotional and psychological complexities of tracing biological origins.

And yet the black market for sperm continues to flourish.

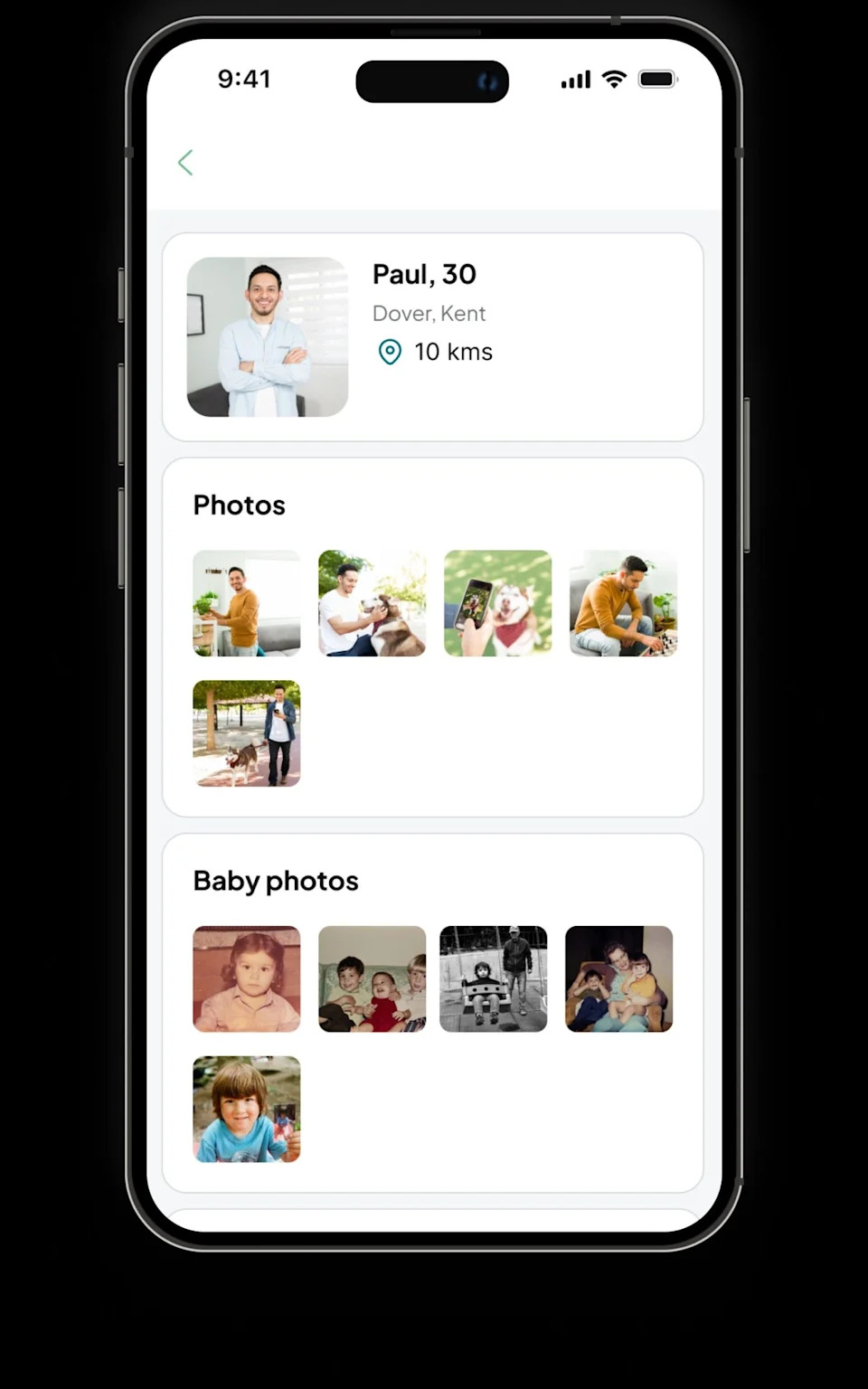

In June, a start-up called The Y Factor launched in Britain, billing itself as “a modern, ethical way” to connect donors and recipients. It looks and behaves like a dating app: users create profiles stating whether they are a donor or would-be parent, upload photographs and list personal details such as age, location and preferred method of conception – whether “DIY” insemination, “natural” intercourse or through a clinic.

The Y Factor app connects donors and would-be parents through dating-style profiles and personal details

Once your profile is live, you can begin scrolling. “Around 70 per cent of donors on the app offer their sperm for free,” says Sofie Hafström Kritsotaki, the app’s co-founder. “While around 40 per cent of future parents are willing to pay the donor for their support.” When you search for a match on the app, you can stipulate whether you want the donation to be “free” or “with compensation”.

“From what we know, if they agree on compensation, it’s usually in the range of £50-£100, to cover time spent and travel costs. This is not arranged through our platform, but between the parties themselves.”

Many donors include both current and childhood photos, giving prospective parents a glimpse of their future child.

There is Juan*, 31, from Catalonia, who prefers “intercourse” as a method of donation; or Stephen*, 41, a bus driver from Somerset seeking home insemination via a clinic. “Always wanted to be a dad but the situation never arose,” he writes. “Not sure it will ever happen for me before I’m too old, but I want to help others achieve their dreams.”

For many women, these platforms offer a pragmatic alternative to the high costs and long waiting lists of licensed clinics. Despite several regulated sperm banks across the UK, supply remains chronically short. Under HFEA rules, an official donor’s sperm can only be used to create a maximum of 10 families – a limit designed to reduce the risk of accidental genetic links.

Official fertility treatment, meanwhile, can be financially crippling. Intrauterine insemination (IUI), where prepared sperm is placed directly into the womb, costs around £1,500 per cycle privately, and in vitro fertilisation (IVF) – where the egg and sperm are combined in a lab and the embryo is then transferred to the uterus – substantially more. NHS coverage varies by region and is often available only after multiple paid cycles have failed. For many single women and same-sex couples, conception through official channels feels financially out of reach.

That economic reality has created a shadow system. And despite the potential pitfalls, unregulated donation offers something the clinics cannot: choice.

“Hi, how picky do you think you can be?” one woman asks on Sperm Donors UK.

“If I was to conceive a son, is it too picky to try to find a donor who also has thick, full hair?” A donor replies: “Absolutely you can be picky. I won’t donate to overweight and unhealthy-looking women.”

For Natalie Lovejoy, 42, from Wiltshire, it was less about choosiness than practicality. “I still hadn’t met anyone and, two years ago, I realised dating apps were awful, and my relationships weren’t going anywhere,” she says. “I know I want a baby, so I’m going to have a baby, and then love will come later.”

Natalie Lovejoy turned to donor apps after hearing that Facebook groups were ‘very sleazy’

From what Lovejoy had heard, Facebook groups were “very sleazy”. “People insist on natural insemination only, and some say, ‘I’ve donated to multiple people’. I think some guys are serial donors or don’t have good intentions,” she says.

The Y Factor felt like a safer middle ground. “It had many more levels of security,” she says (the app includes ID verification and blocking tools to reduce the risks of fraud or misconduct, as well as educational articles and health advice). “You’re matching with people who have the same intentions as you, the same method of donation, the same desire for contact afterwards.”

The “official” route was simply not financially viable for her: “Without using social media funding or starting a GoFundMe, it’s not something I could do on my salary,” says Lovejoy, who works for a wedding company. She has been trying to conceive with two donors for more than two years.

Since The Y Factor’s launch, its user numbers have almost doubled every week, and it now hosts more women and couples seeking sperm than it has active donors.

“There’s definitely a shortage,” says Hafström Kritsotaki. “There’s a lack of donors from specific ethnicities or backgrounds, and some people want someone who resembles their partner. A baby shouldn’t be designed based on height or eye colour, but many want to meet the donor and talk, because they believe a child inherits more than physical traits.”

Sofie Hafström Kritsotaki, co-founder of The Y Factor, says donor shortages are shaping how people search online

For some men, she adds, donating can offer a sense of legacy. “We have a lot of donors interested in co-parenting. It allows them to help someone else while still feeling part of the story.”

One 34-year-old donor from London, who uses Sperm Donors UK, says: “I don’t have any children of my own. This way, a part of me will still live on, and I know how happy it makes the people I donate to.”

Why Facebook rather than a clinic?

“With this approach, both parties can talk and get to know each other. It feels more human than frozen sperm from a clinic.”

But experts remain uneasy.

Clare Ettinghausen, director of strategy and corporate affairs at the HFEA, says: “Apps like The Y Factor, websites or social media sites that encourage unregulated or private donation cut corners and expose people to serious medical, legal and emotional risks. It is always safer to have treatment at a licensed clinic, where laws and guidance protect patients and donors.”

Earlier this year, a family court took the extraordinary step of naming Robert Charles Albon, who presents himself online as “Joe Donor”, in order to warn women about the dangers of unregulated sperm donation. Albon, who claims to have fathered more than 180 children around the world, had donated sperm to a same-sex couple who conceived by syringe insemination.

He later alleged, falsely according to the court, that he had secretly had sex with the biological mother. The court heard that he had met the child only once, briefly, for a photograph, yet went on to seek parental responsibility, a place on the birth certificate and permission to alter the child’s name.

The judge described his behaviour as troubling and manipulative, warning that private arrangements made outside licensed clinics leave women legally and emotionally vulnerable.

Nina Barnsley, director of the Donor Conception Network (DCN), adds: “Donors are [also] putting themselves at risk because they could be considered the legal parent of the child. And women are also vulnerable, because the man could make a claim to the child. That legal clarity simply doesn’t exist outside of regulated clinics.”

The Y Factor says it offers choice and flexibility, but warns UK laws leave modern family structures legally exposed

The Y Factor acknowledges that clinics are the “safe and preferred choice for many” but blames current legislation for giving sperm banks and clinics a “monopoly” on legal protection.

“Private donation contracts are sadly not legally binding in the UK yet,” it says. “This is despite recent voices calling known-donor setups more ethical for the future child. The current legal framework is made for nuclear families. Many of today’s modern family structures simply do not fit the mould, exposing solo parents and co-parenting arrangements to more legal risks.”

Meanwhile, Meta, the owner of Facebook, says it is investigating Sperm Donors UK. According to the company’s policies, the advertising of human fluid donations, such as semen, is permitted, but the buying, selling or trading of these materials is prohibited.

Still, for many, the appeal of autonomy outweighs the danger. In an era when parenthood can feel both precarious and commodified, the new sperm economy offers something bluntly empowering – if also unsettling.

As Lovejoy puts it, “The crux of it is, people don’t want to miss out on motherhood or rely on a man to make it happen.”

*Some names have been changed

First Appeared on

Source link