360 Million Years Ago, Cleveland Was Home to a Monstrous Predator With Bone Blades Instead of Teeth

Roughly 360 million years ago, a shallow sea covered what is now Cleveland, Ohio. In its depths lurked Dunkleosteus terrelli, a 14-foot armored fish armed not with teeth, but with sharpened bone blades. For decades, this Devonian-era apex predator has stood as the textbook example of an early jawed vertebrate—one of evolution’s early experiments in building a super-predator.

But a new study, led by researchers at Case Western Reserve University, has rewritten what we thought we knew. Far from being a model arthrodire—a now-extinct group of armored, shark-like fishes—Dunkleosteus turns out to be an evolutionary outlier. Its skull was nearly half cartilage, and its jaw anatomy shares unexpected similarities with modern sharks and rays.

This work marks the first comprehensive anatomical reassessment of the species in nearly a century. It’s a striking reminder that even the most studied prehistoric icons can still surprise—and challenge—our assumptions.

“Dunkleosteus actually was not like most of its kin, and was in fact, a bit of an oddball,” said Case Western’s Russell Engelman, a graduate researcher and lead author of the study.

a closer look reveals a stranger fish

Published in The Anatomical Record, the study is the most detailed anatomical investigation of Dunkleosteus since 1932. According to Engelman, that early work was largely about figuring out how the fragmented bones fit together. Modern tools and decades of fossil discoveries have now allowed for a deeper look—not just at structure, but at function and evolutionary context.

The research team, which included scientists from Russia, the UK, Australia, and Cleveland, reexamined fossils from the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, home to the largest and best-preserved collection of Dunkleosteus remains in the world. These fossils were entombed in Devonian black shale, preserved by ancient seafloor conditions and frequently uncovered by construction projects.

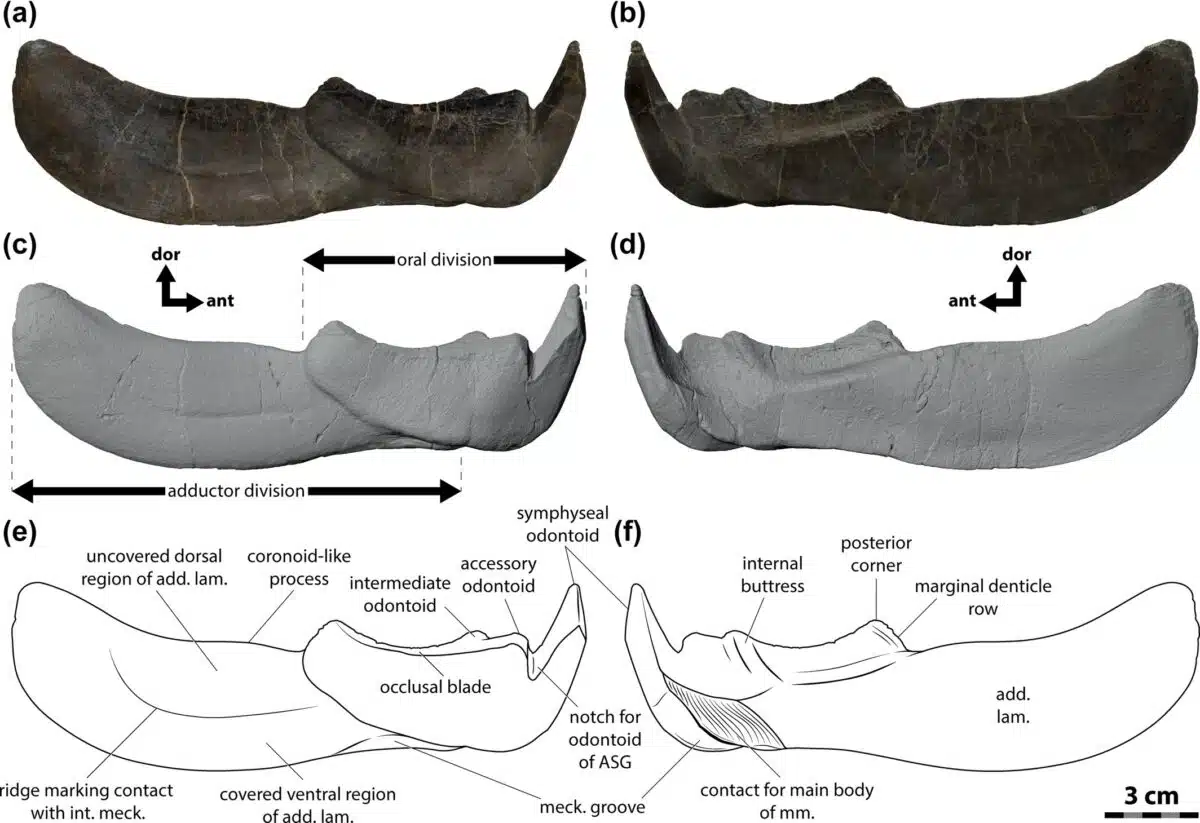

Among the more surprising discoveries: nearly half of the predator’s skull was cartilage, including many major jaw joints and muscle attachment points. That composition is highly unusual for armored fishes of the time. Even more remarkable was the presence of a large bony canal that housed a jaw muscle similar to those seen in modern sharks and rays—a rare feature in ancient vertebrates and one that hints at different mechanics than previously thought.

“More recent studies have tried biomechanical modeling of Dunkleosteus, but no one has really gone back and looked at what the bones themselves say about muscle attachments and function,” Engelman explained in the university’s official release.

more knife than teeth

While Dunkleosteus is often presented as representative of arthrodires, the study shows it was anything but typical. Most members of this ancient clade had true teeth. Dunkleosteus, however, and a few close relatives, lost those teeth—evolving instead a pair of sharpened bony blades in the jaw capable of slicing flesh with shearing force.

These blades likely evolved independently within several lineages of arthrodires, as part of an arms race among large marine predators during the Devonian. Engelman’s team believes these specializations allowed Dunkleosteus to hunt large, bony prey, using its powerful jaws to carve out substantial bites rather than swallowing prey whole.

“This ancient predator has remained scientifically neglected for nearly a century,” the researchers noted in the Case Western report. Their findings underscore that Dunkleosteus was not a primitive generalist, but a highly specialized carnivore that carved out its own ecological niche in a competitive environment.

implications for paleontology—and beyond

The study doesn’t just offer a new take on one prehistoric predator. It reconfigures how researchers approach arthrodire evolution and the broader narrative of early vertebrate development.

“These discoveries highlight that arthrodires cannot be thought of as primitive, homogenous animals, but instead a highly diverse group of fishes that flourished and occupied many different ecological roles during their history,” Engelman said in the IFLScience article.

This revised view of arthrodires as a complex, diverse group challenges longstanding generalizations. It also raises questions about the assumptions paleontologists may be making with other well-known fossil species. If Dunkleosteus, one of the most studied and reconstructed Devonian fishes, was so poorly understood for so long, what else might be hiding in plain sight?

Furthermore, it underscores the value of reexamining existing fossil collections with fresh eyes and modern tools. Despite the Cleveland collection being available for decades, no one had conducted a full anatomical reassessment until now.

paleontology’s future is in the details

The real shift here is methodological. The field is increasingly moving away from artistic reconstructions and surface-level analysis and toward high-resolution, anatomy-driven research—a trend this study exemplifies.

We still don’t know exactly what the rest of Dunkleosteus’ body looked like. The fossil record primarily preserves its armored head and upper torso; its fins, tail, and much of its musculature remain unknown. That missing information continues to complicate reconstructions of its swimming capabilities and hunting behavior.

But the deeper message is clear: even fossils displayed in museums for generations can still hold transformative secrets—if we’re willing to look closer.

First Appeared on

Source link