Time, Date and Who Will Actually See It

A rare alignment between the Sun and Moon will soon produce a ring-shaped eclipse over Antarctica. Known as an annular solar eclipse, the event occurs when the Moon passes in front of the Sun while positioned near its farthest point from Earth, leaving a narrow band of sunlight visible around the lunar disc. The result is a sharp, luminous ring suspended in the sky—brief, calculable, and geographically precise.

The eclipse’s path has been charted in detail; its timing, down to the second. Yet the phenomenon reveals more than celestial mechanics. It exposes how access to scientifically valuable events is shaped not just by interest or capability but by the physical geography of Earth itself. Where observation is possible, participation is often not.

Rare Phenomenon, Limited Reach

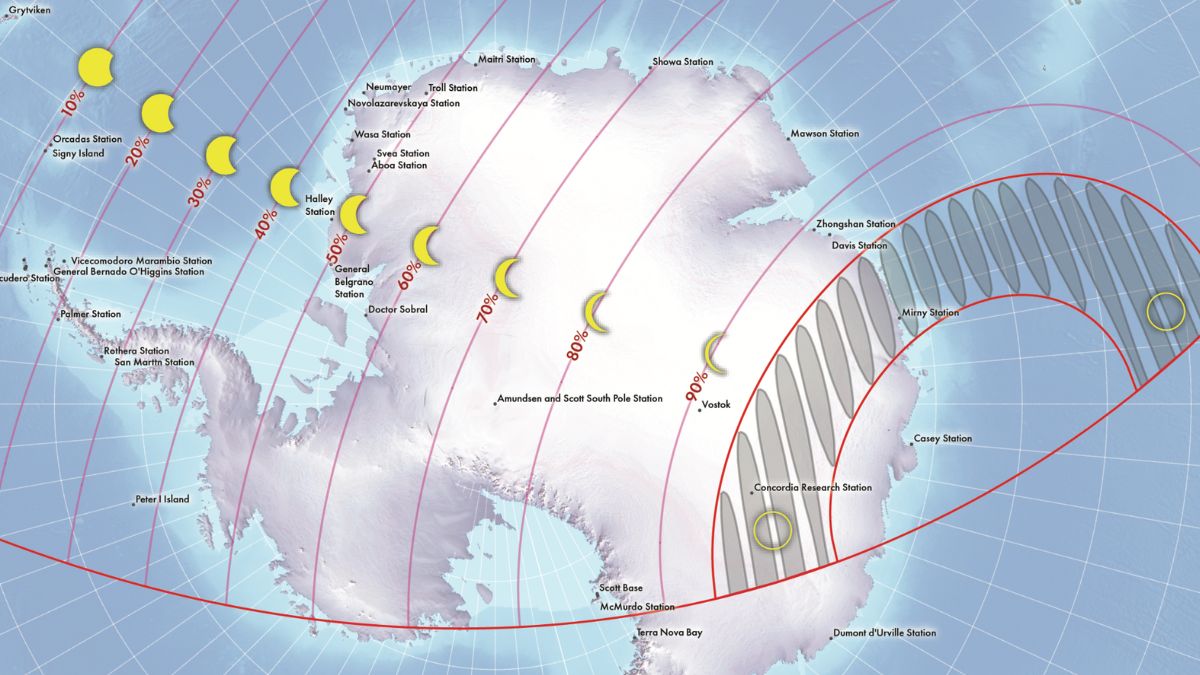

February 17, 2026 event marks the first solar eclipse of the year. The path of annularity spans approximately 4,282 kilometres in length and 616 kilometres in width, as detailed by eclipse cartographer Michael Zeiler. The Moon will obscure 96 percent of the Sun’s surface at maximum, forming the characteristic “ring of fire”. Duration within the centreline will range from just under two minutes to just over two minutes, depending on location.

Scientific definitions published by NASA Science explain that annular eclipses differ from total eclipses in one key aspect: the Moon’s apparent size is smaller than the Sun’s due to its greater distance from Earth. This geometry results in a visible ring of solar light rather than full obscuration.

Meteorological projections compiled by atmospheric scientist Jay Anderson through his Eclipsophile project indicate that cloud cover is likely to vary significantly across the eclipse path. As noted in his analysis, coastal areas near the Davis Sea face up to 65 percent cloud probability during the annular window, while the inland zone—particularly near Concordia Station—shows lower expected coverage closer to 35 percent.

Science Locked Behind Ice and Protocol

Scientific instrumentation in the eclipse path is limited. Only two fixed research sites—France and Italy’s Concordia Research Station and Russia’s Mirny Station—fall within the corridor of annularity. Both operate seasonally and are governed by international frameworks that restrict access to third parties. No mobile observatories or eclipse-specific deployments have been registered for the region.

Facilities within this corridor are designed for long-term data collection, including:

- high-elevation atmospheric towers

- surface-based radiometers and solar flux sensors

- satellite calibration instruments

- self-contained power and data relay systems

These platforms are not configured for rapid optical acquisition. The absence of redundancy poses significant risk. Single-point failures such as:

- persistent low-altitude cloud

- hardware malfunction under extreme cold

- incomplete or delayed data transfer

could nullify observational efforts.

Despite the event’s scientific relevance, no coordination plan has been made public by Antarctic treaty members or space agencies. As reported by Space.com, tourism-based viewing is unlikely due to seasonal limitations, regulatory constraints, and the extreme remoteness of the annular corridor.

When the Sky Darkens but Few Can Look Up

Celestial events with high research value are not uniformly accessible. Annular eclipses can be used to measure solar irradiance, aerosol response, and eclipse-induced atmospheric changes, but data capture is often dictated by infrastructure rather than need. Most facilities capable of conducting high-resolution observations are located far from the eclipse zone.

By comparison, the 2017 and 2024 total solar eclipses over North America were visible to tens of millions and supported by institutional planning and dedicated scientific campaigns. The Antarctic event offers none of these advantages. As noted in the annular eclipse overview on Space.com, even Concordia Station—arguably the best-positioned site—houses just 16 researchers during the peak summer season.

This disparity reflects broader systemic gaps in global observational science. Data from events like this remain vulnerable to weather, underinvestment, and logistical isolation, regardless of their scientific importance.

First Appeared on

Source link