A life-saving machine developed in the 1970s is finding renewed purpose post-pandemic

Kelli Gehrke, 36, had been in cardiac arrest for seven minutes when a mobile team of doctors and specialists flown in from Harborview Medical Center connected her to a life-saving machine that bypassed her failing heart and lungs.

Three days earlier, Kelli Gehrke had traveled with her husband Chris Gehrke from their home in Lacey, Washington, to Madigan Army Medical Center in Fort Lewis for the birth of their third child.

But things had not gone according to plan. After an emergency C-section, Kelli Gehrke suffered a rare amniotic fluid embolism, causing amniotic fluid from the womb to enter her bloodstream.

During the birth and the complications that followed, Kelli Gehrke lost the equivalent of six people’s worth of blood. Chris Gehrke said doctors told him his wife was losing so much blood, Madigan used everything it had on hand and still needed emergency donations from 72 people to save her life.

That’s when a Madigan doctor trained in its use suggested the hospital seek out Harborview’s mobile extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine to help Kelli Gehrke.

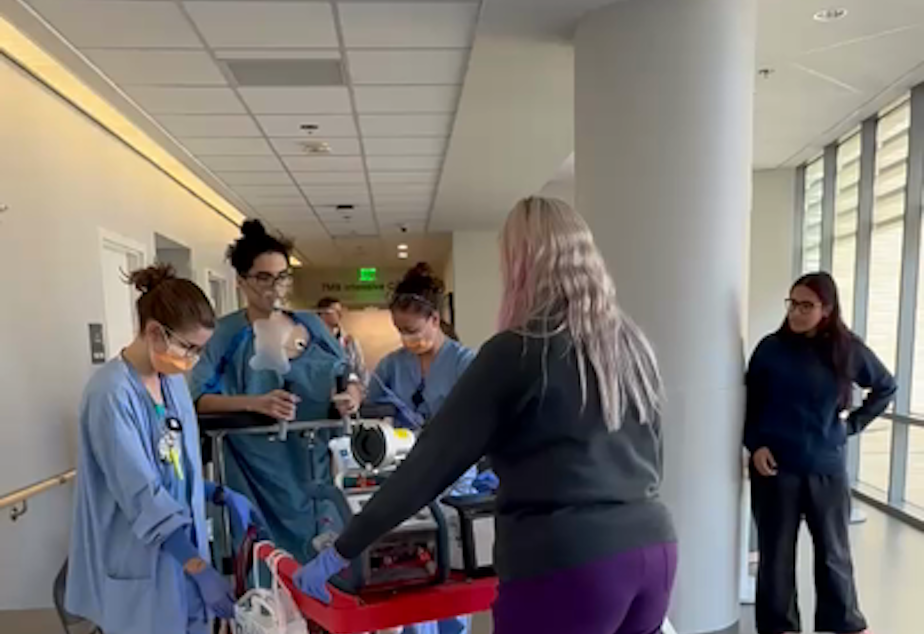

“They life-flighted the ECMO team out there and when they arrived, her heart rate, everything was super low,” Chris Gehrke said. “As they set up the machine, she went into cardiac arrest.”

One team was giving his wife CPR while another was attaching her to the ECMO, a process called cannulation that involves inserting large tubes into major blood vessels in the neck, groin, or chest.

“When they put the ECMO into her, she had already passed away,” Gehrke said. “When they started the machine, it actually kicked her right up to life.”

RELATED: Amid funding cuts and public health battles, NIH issues autism research grants

ECMO machines have been around for more than 50 years. For much of that time, they were used primarily to help patients survive while they waited for an organ transplant. But in the last 10-15 years, and especially since Covid, they are being used as a last-ditch effort to stabilize patients whose lungs or hearts are failing.

The UW Medical Centers at Montlake and Harborview have been on the forefront of this expansion. The two hospitals went from having three ECMO machines in 2012 to 13 in 2025. Last year, they used the machines on 130 patients total, 65 of whom survived.

UW Medicine also has mobile ECMO teams, like the one that helped Kelli Gehrke, that can be deployed throughout the Pacific Northwest for patients who are too medically unstable to transport.

Around 50% of patients who are put on an ECMO survive. But that coin-toss survival rate is deceptive.

For people with lung failure, the survival rate is closer to 70%. The survival rate for people like Kelli Gehrke who are in cardiac arrest is closer to 30%. But the survival rate without the machine for those patients is nearly zero, said Dr. John Scott, a trauma surgeon at the UW Medicine Department of Surgery and the medical director of Harborview’s ECMO program.

“Patients are not statistics,” Scott said. “For that patient who is clearly on the verge of death, and you put them on [an] ECMO, and they walk out of the hospital, that changes your whole career.”

Buying time

One of the key medical takeaways from the pandemic was the limitations of widely available emergency measures to successfully treat acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). For thousands of Covid patients, the only immediate option was intubation, but that carries risks of infection and other complications.

“It’s basically a plastic tube highway for bacteria to enter the lungs and get them re-infected,” said Dr. Jenelle Badulak, associate director of the UW Medicine ECMO program.

During the pandemic, hospitals and doctors became experts in treating lung failure, and they recognized the value of having ECMO machines to bypass the lungs as a last resort.

There are two types of ECMO machines — one that bypasses the lungs only and oxygenates the blood while the patient’s heart continues to pump and a second machine that takes over both heart and lung function.

“Covid was a crash course in treating ARDS,” Scott said. “A lot of hospitals became a respiratory failure unit overnight. As a result, when we get these calls, so many places have been doing all the hard work. They’ve been doing all the right things, and the patients just aren’t responding.”

That was the case with 20-year-old Ethan Noack, a junior studying computer engineering at the University of Washington in Tacoma. Noack started having trouble breathing several days after he had surgery to repair torn ligaments in his wrist.

His mother Elaine Martins Noack took him to the emergency room where X-rays showed damage to his lungs that was inconsistent with a healthy teenager with no history of respiratory disease. Ethan Noack was moved to Tacoma General Hospital, but his lungs kept getting worse and his doctors couldn’t figure out why. After a week, he was intubated and airlifted to Harborview, where he was put on a lung-bypassing ECMO.

Shortly after his arrival in Seattle, one of the Harborview residents forwarded an article to Martins Noack about a rare reaction to the antibiotic Bactrim, a drug that her son had been on before and after his wrist surgery.

“As I read the article, I was first terrified because that child has suffered so much,” she said. “There was something in me that told me that’s why he was sick.”

When doctors biopsied Noack’s lungs, they confirmed that he was one of only a few dozen verified cases of people who suffered severe ARDS after taking Bactrim.

Dr. Scott said an ECMO buys time for medical staff to evaluate and diagnose challenging cases like Noack’s and gives the body time to do what it does best — heal itself.

“ECMO doesn’t cure the lungs,” he said. “ECMO rests the lungs and makes sure the body gets the oxygen it needs while the lungs can recover on their own.”

Air hunger

Noack, who was on an ECMO for more than a month, was determined to become Harborview’s first patient to walk while hooked up to the machine. He said his primary inspiration was the music of Kendrick Lamar.

The staff created a playlist to help get Noack motivated. His mother said it took 10 people to get him walking. They turned the music up extra loud so it wasn’t drowned out by all the beeping and humming of the machines that were keeping Noack alive.

“Each day was a different song, and each day he would walk a little more,” Martins Noack said.

In addition to these small triumphs, her son also endured anxiety, depression, and fear. One of the most challenging things about being awake on ECMO is a side effect called “air hunger,” an intense feeling of suffocation because the patient is awake but not breathing.

Dr. Badulak said rehab psychologists work with ECMO patients, especially during the first few days, to help them overcome the panic of not being able to fill their lungs with air.

For Martins Noack, the memory of her son struggling to breathe was particularly challenging.

“He would lose control of his body and believe that he was dying even though I was telling him, ‘You’re not dying. You’re not drowning,’” she said.

The trauma of what her son has been through has shaken Martins Noack’s confidence, even now that he is back home and recovering.

Every time she gets in a car, she worries about getting in an accident, she said. When she takes Ethan for a checkup, she thinks, “What if I get in a wreck and he doesn’t have enough oxygen?”

“Just the fragility of existence is something I think will change anyone,” she said.

Road to recovery

Every successful use of an ECMO is the story of a life saved. But many families who come out on the other side may find their lives turned upside down as they struggle to recover from an emergency that almost killed them.

Kelli Gehrke is relearning to walk. She now has a drop foot from where the ECMO was inserted near her groin. Her kidneys were damaged during her illness. She gets dialysis eight hours a week and might need a kidney transplant.

Ethan Noack remains on oxygen at his home in Lake Tapps, Washington. Doctors determined, at the last possible minute, that he does not require a lung transplant.

But questions remain about whether scar tissue will develop around the small holes in his lungs, which could prevent him from a full recovery and restrict him from eventually doing the things he loves, like playing basketball with his friends.

The financial toll

The cost of an ECMO treatment at UW Medicine is about $13,000 a day, according to spokesperson Susan Gregg. While reimbursement levels vary depending on the patient’s health insurance, they also face the challenge of making ends meet during extended recoveries that can last months or years.

RELATED: Trump might shut down UW’s Primate Research Center. Should he?

For example, Chris Gehrke has not been able to go back to work as a truck driver because he is taking care of his wife, their new baby, and their two other boys, who are 15 and 12.

The baby, Max, refuses to nap. During his mother’s illness, he bonded with his father’s chest, the only thing that calms him. But at least he’s healthy.

“He’s good,” Kelli Gehrke said. “I’m the one that took the hit, but I’ll take it as long as he’s OK.”

As for Ethan Noack, he’s happy to be back home with his dogs — Gigi, a shiatsu, Bruno, a corgi, and Sebastian or Seba, the wiener dog.

Friends of the Noack and Gehrke families have set up GoFundMe pages to help cover the costs of their ongoing health crises and recovery process.

Making the call

Both Scott and Badulak are part of a specialized medical team that decides whether patients would benefit from an ECMO.

The group considers multiple factors in making what is often a life-or-death decision. Do the benefits of the ECMO outweigh the risks? Is the patient’s illness related to their lungs or heart or are they in danger because of something else, such as liver failure, which an ECMO can’t help? What’s the likelihood the person would survive attachment to an ECMO? What would their quality of life be if they did survive?

RELATED: Supreme Court allows NIH to stop making nearly $800M in research grants for now

The program’s advancement combined with more available machines has led UW Medicine to approve more ECMO patients – people they wouldn’t have in previous years, Badulak said.

“The benefit of us being a high-volume platinum center is that we just have so much experience now that we get braver and braver with our patient selection,” she said. “Patients are surviving that maybe we thought wouldn’t. That helps embolden us to continue pushing boundaries.”

Badulak said the challenge now is to get the word out to rural hospitals that have patients who might survive if they had access to a mobile ECMO team.

“Call us if you have someone who is dying from heart or lung failure, because we may be able to come out and put them on ECMO and save them,” she said. “Not everybody is a candidate for this, but we really want to hear from everybody, because each patient is unique.”

First Appeared on

Source link