A Thin Line in the Ocean Is Doing What We Thought Was Impossible

New research featured on Nature Climate Change reveals ocean fronts are places where different water masses meet, usually with changes in temperature, salinity, density, and major impacts on carbon dynamics. While they don’t take up much surface space, they’re packed with activity. Until now, they’ve mostly been left out of large-scale climate models, which tend to focus on broader ocean areas and miss these smaller, more dynamic regions.

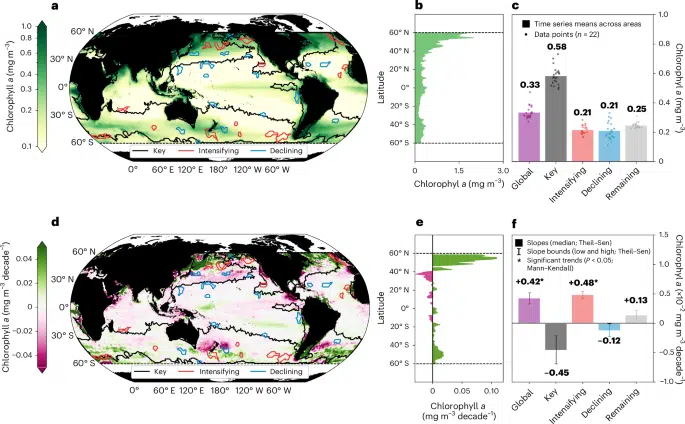

The research team used two decades of satellite observations to link front activity to phytoplankton blooms and CO₂ absorption. They found that these fronts act like carbon sponges, trapping large amounts of atmospheric carbon. Ignoring them in calculations may have led to big underestimates of how much carbon the ocean is actually storing.

Small Zones With A Big Carbon Punch

According to the study, ocean fronts absorb significantly more carbon dioxide than nearby waters. Even though these zones are relatively small, they show up again and again as CO₂ hotspots. They’re places where energy and nutrients mix constantly, which creates the perfect conditions for life, and carbon capture.

One key factor is vertical mixing. In many fronts, cold, nutrient-rich water rises from below, which feeds phytoplankton at the surface.

“These microscopic plants absorb carbon dioxide as they photosynthesize. And when they die, they sink, carrying carbon into the deep ocean where it can remain locked away for centuries,” explained Dr. Amelie Meyer, IMAS oceanographer and co-author of the study.

Phytoplankton Thrive At The Edges

The same satellite data showed higher levels of phytoplankton biomass right at ocean fronts. Since phytoplankton are the base of the marine food web, their abundance means these regions are not just carbon absorbers, they’re biological powerhouses. More phytoplankton means more photosynthesis, and more photosynthesis means more CO₂ taken from the air.

What’s interesting is how consistent this pattern is. The study didn’t just find a few isolated events. Across two decades, ocean fronts regularly showed high biological productivity.

“Where fronts are intensifying, carbon dioxide uptake is strengthening at twice the global average rate. Where they’re declining, carbon absorption is weakening,” said the author of the research, Dr. Kai Yang said.

Climate Models May Be Missing Key Data

One of the most important takeaways from this research is that many climate models might be missing a big piece of the puzzle. These models usually work at lower resolution and can’t capture narrow features like ocean fronts. That could mean they’ve been underestimating ocean carbon uptake for years.

As highlighted by Phys.org, the authors argue that future models need to include these small-scale dynamics. With today’s satellites and high-resolution data, it’s now possible to monitor fronts and their impact more closely. Updating models with this kind of detail could make a real difference in how we understand and predict the carbon cycle.

First Appeared on

Source link