Archaeologists Found a 800,000-Year-Old Human Footprints Under UK Sand, And They’re Perfectly Preserved

Footprints dating back 800,000 years have been uncovered on a beach in Norfolk, England, offering one of the oldest direct records of early human presence in northern Europe. Discovered at Happisburgh, these ancient impressions, left by both adults and children, mark a rare moment frozen in time, now preserved only through digital models.

This remarkable find, announced by archaeologists in early 2014, places Britain on the map of deep human history. Until now, most evidence of such early hominin activity had come from warmer regions; the Happisburgh footprints push the known northern limits of prehistoric human movement in Europe far beyond previous expectations.

A Chance Find That Changed Everything

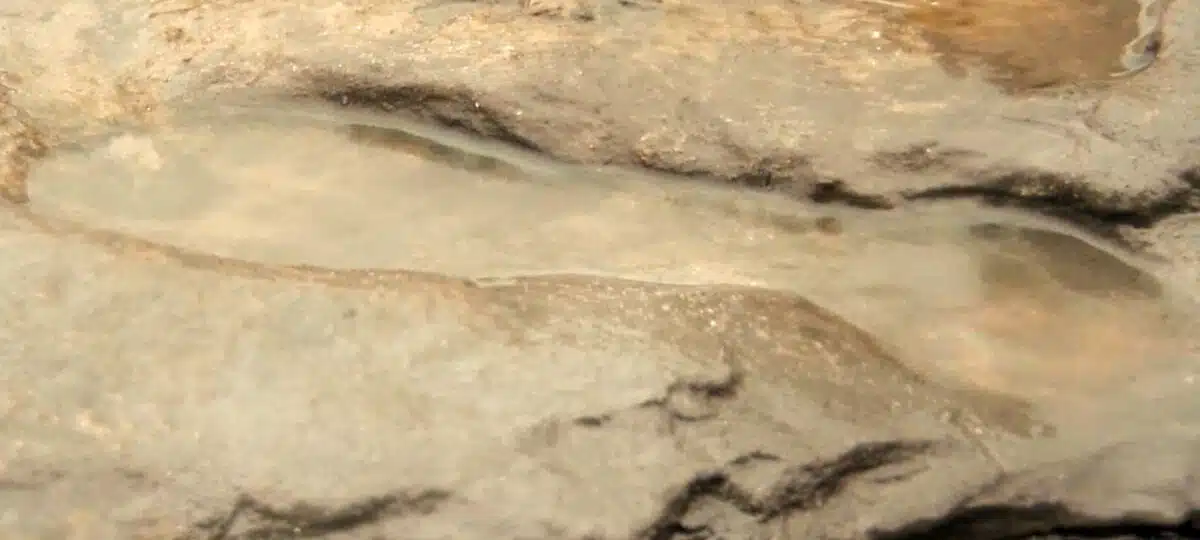

In May 2013, shifting sands at Happisburgh, a village on England’s eastern coastline, revealed shallow depressions that looked oddly familiar. As researchers removed seawater and sand from the fragile surface, their suspicion was confirmed: these were human footprints. A team led by Dr. Nick Ashton from the British Museum quickly used photogrammetry to digitally capture the site before the sea reclaimed it.

The analysis, published in PLoS ONE, showed that the elongated hollows were left by at least five individuals, including adults and children. Some impressions were so clear that heel marks, arches, and even toes could be identified. One of the prints matched a modern US shoe size 9-10, suggesting the presence of a tall adult male, while smaller footprints pointed to much shorter individuals, likely children.

Using modern ratios between foot size and height, researchers estimated the ancient walkers ranged from 0.9 meters to over 1.7 meters tall. The team believes the footprints were made as a group moved together along the edge of an estuary, possibly searching for food or relocating as a family unit.

Ancient Britain’s Lost Landscape

The sediments that preserved the Happisburgh footprints belong to a layer of ancient river valley deposits that predate the Ice Ages. At the time, Britain was not an island, but part of mainland Europe. The area was a rich and varied ecosystem: a wide estuary flowed nearby, surrounded by mudflats, salt marshes, and coniferous forests.

Fossils found in the same sediments include remains of mammoth, hippo, deer, bison, and even rhinoceros. These animals likely grazed along the floodplain, offering early humans ample opportunities for hunting and scavenging. The estuary also provided edible plants, tubers, shellfish, and seaweed, making it a vital hub for survival.

Preserved pollen, beetles, and plant remains helped scientists reconstruct the environment in detail. The location would have been just a few miles inland at the time, far from the modern-day coastline. The fact that these footprints survived erosion for so long, and were then exposed for only a few days, makes the discovery all the more remarkable.

Who Walked These Ancient Shores?

Although no human bones were found at the site, researchers believe the footprints may belong to Homo antecessor, an early human species known from fossil remains in Atapuerca, Spain.

“These people were of a similar height to ourselves and were fully bipedal. They seem to have become extinct in Europe by 600,000 years ago and were perhaps replaced by the species Homo heidelbergensis. Neanderthals followed from about 400,000 years ago, and eventually modern humans some 40,000 years ago,” explained Professor Chris Stringer, at the Natural History Museum in the UK.

The Happisburgh footprints are now among the very few ancient human trackways ever discovered. The British find stands out not only for its age but for its location in a relatively cold northern environment, far from the equatorial zones where early human evolution began.

“These footprints provide a very tangible link to our forebears and deep past,” said Dr. Ashton.

Within just two weeks of their discovery, the waves had erased every visible trace of the ancient tracks. Thanks to rapid digital recording, however, these brief footprints have been preserved virtually.

First Appeared on

Source link