Artificial Intelligence Reveals Fingerprints Aren’t Truly Unique, Debunking 100 Years of Forensic Science

Forensic science has long held that fingerprints are singular identifiers, unique to each finger and each individual. This assumption has formed the backbone of global law enforcement, identity verification, and legal proceedings for more than a century.

Fingerprint evidence has been widely accepted in courtrooms and biometric systems based on the belief that no two fingerprints are alike, not even between different fingers of the same person. That premise now faces a serious challenge from a new generation of artificial intelligence research.

A recent study led by computer scientists in the United States has introduced compelling evidence that some structural features of fingerprints recur across all ten fingers of an individual. These similarities, invisible to human examiners, have been identified by a machine learning model trained to detect previously unrecognized biometric patterns.

AI Cracks the Code on Cross-Finger Similarities

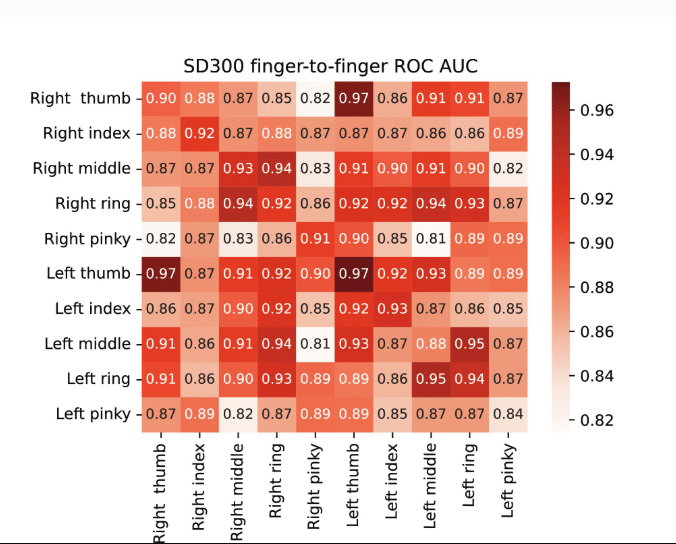

In findings published in Science Advances in January 2024, researchers at Columbia University and the University at Buffalo demonstrated that an artificial intelligence model can detect intra-person fingerprint similarities across different fingers. The study used deep contrastive learning, training a twin neural network on over 60,000 fingerprint images sourced from four major biometric datasets.

The system reached over 99.99 percent confidence in determining whether two fingerprints belonged to the same person. It also achieved 77 percent accuracy in identifying prints from different fingers of the same individual, a figure that increased significantly when multiple fingerprints were combined in the analysis.

Rather than relying on minutiae, such as ridge endings and bifurcations, which are standard in forensic fingerprint matching, the model used features like ridge orientation and curvature. These broader structural patterns, the study found, appear consistently across a person’s fingers, even between hands.

The datasets used included the widely referenced NIST SD300 and SD302 fingerprint benchmarks, along with the RidgeBase biometric dataset developed at the University at Buffalo. The researchers controlled for external variables, such as fingerprint sensor type and sampling session, to ensure that the similarities detected were not influenced by environmental or hardware factors.

New Tech Slashes Suspect Lists in Seconds

Fingerprint evidence has traditionally depended on matching a recovered print to a known finger within an existing database. That process can be slow, especially in investigations involving large suspect pools. Current systems often require all ten fingerprints of each subject to be available for cross-matching.

The new AI method offers a substantial efficiency gain. In one simulated forensic test, the model reduced a suspect list of 1,000 individuals to fewer than 40 likely candidates. By identifying recurring structural features across fingers, the AI can connect fingerprints found at separate crime scenes, even if they come from different fingers.

This capability may prove especially useful in cases involving partial, smudged, or low-quality prints, which are common at crime scenes. Traditional matching systems tend to struggle when prints are incomplete or when the finger used is not already known.

Despite these promising results, the research team has emphasized that the AI is not currently suitable for courtroom use. Accuracy rates, while improving, still fall below the reliability threshold of conventional same-finger matching systems. The model’s intended use is investigative lead generation, not legal identification.

Forensics Rethink: Orientation Over Minutiae

The study found that ridge orientation, particularly in the central region of the fingerprint, was the most influential factor in detecting cross-finger similarity. In contrast, minutiae—long considered the gold standard for fingerprint comparison—contributed very little to intra-person matching in this context.

Binarized images and orientation maps performed nearly as well as original scans in the model’s accuracy metrics. This suggests that essential fingerprint traits may be simpler and more broadly distributed than previously understood.

The researchers visualized the model’s internal processes using saliency maps and convolutional filters. These revealed that the AI focused primarily on areas with high directional changes in ridge flow, such as fingerprint deltas. The similarity remained statistically significant across all combinations of finger pairs, even between hands.

The study also tested the model on the NIST SD301 dataset, which was collected under different experimental protocols. Results from that dataset remained consistent with those from the primary datasets, indicating that the model generalizes well across varying sources.

Security Systems May Need a Fingerprint Reality Check

Beyond forensics, the findings may affect the future of biometric security, including devices like smartphones, access controls, and border identity checks. These systems typically assume that each enrolled fingerprint represents a distinct identity marker.

The possibility of cross-finger similarity introduces both risks and benefits. Malicious actors might exploit structural similarities to bypass authentication by using a different finger than the one originally registered. On the other hand, users may benefit from more flexible authentication, especially when the primary finger is injured or unreadable.

To support training, the model was initially pre-trained using the synthetic fingerprint dataset known as PrintsGAN, which includes more than 500,000 artificially generated fingerprint images. This pre-training step improved the AI’s ability to recognize ridge-based features before fine-tuning on real-world samples.

The model’s performance was also evaluated across gender and racial groups. It remained generally consistent, although slightly higher accuracy was recorded when training and testing occurred within the same demographic. These findings underscore the importance of representative training datasets and raise concerns about potential algorithmic bias in forensic tools.

Researchers used a balanced demographic subset of the SD302 dataset for this testing phase. Although group-specific variance was low, the team recommended expanding future models to include larger and more diverse populations.

First Appeared on

Source link