At Mass. brain bank, cuts may hinder cutting edge research

“It quite literally will melt in your hands,” said Grace Nyanchoka as she handled the spongy mass of tissue. “We try to move fast while it’s still firm.”

Now, the nearly 50-year-old center, located on the McLean Hospital campus in Belmont, is itself moving with urgency to stave off a possible 35 percent budget cut by the end of October that could seriously hinder its ability to obtain new donations, said Dr. Sabina Berretta, the center’s director.

And that in turn could disrupt research on a number of conditions that require samples from hundreds of brains at a time.

“As a field, we’re going through that material very quickly,” said Steven McCarroll, who runs a Harvard lab studying conditions including schizophrenia and Huntington’s disease. “It is a moment where the field needs to be doing so much more with this, not less.”

The Harvard center, a repository for more than 8,000 individual brains, is one of the largest of its kind in the country. Over its history, it has contributed to thousands of peer-reviewed research studies and helped unravel the mysteries of nervous system disorders from the extremely rare to the all-too-common.

The Harvard center is one of six repositories in the National Institutes of Health’s NeuroBioBank. The others are in Baltimore, Los Angeles, Miami, New York City, and Pittsburgh. All have been told their funding would be reduced when their contracts expire on Oct. 31. Each has been negotiating with the NIH for less “draconian” reductions, said Thomas Blanchard, an immunologist and director of the University of Maryland Brain and Tissue Bank.

The negotiations had been on hold altogether because of the government shutdown, but Blanchard said he heard from an NIH worker this week that the agency was working to finalize his contract. The staffer informed Blanchard the agency is reviewing his counterproposal, but even that less drastic cut would still require the center to scale back its activities, he said.

The NIH confirmed recently to the Massachusetts facility it had received its budget counterproposal, but it was unclear whether the agency was accepting it, Berretta said.

At stake, Blanchard said, are the banks’ ability to gather donations of new brains from across the country. Restricting their reach to donations from their local regions, he said, would limit the diversity of samples they could collect and risk a shortage of tissue for study.

That wide mix of samples is especially important for the study of rare diseases such as Huntington’s, which afflicts about 41,000 Americans, according to a 2020 study.

“If you cannot recover across the country and you need to rely on local donations, you’re not going to get many,” Berretta said. “There are other disorders that are even more rare.”

Transferring a brain long distances can cost up to $15,000 and involves complex coordination among doctors, families, funeral homes, researchers, and couriers. And it all has to happen within 24 hours, because brain matter begins degrading almost immediately after death.

Threats to the nation’s brain banks couldn’t come at a worse time. Recent technological advances allow detailed analysis of brain tissue at the cellular level, giving scientists new insights into how groups of genes are linked to deadly conditions such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, as well as some forms of mental illness.

“The ability to make biological discoveries from human brain donations has been multiplying exponentially over the last few years,” said McCarroll.

McCarroll and Berretta’s work on Huntington’s has begun to shed light on why the disease doesn’t typically cause symptoms until sufferers are in their 30s to 50s. Tissue from Huntington’s patients revealed the condition gradually increases expression of a certain DNA sequence in brain cells throughout a person’s life. It’s the cumulative effect of that process that begins causing neurological changes. The discovery is shifting the focus of research into treatments, McCarroll said.

A single study can require tissue samples from hundreds of brains. Those samples are often no larger than 10 milligrams, roughly comparable to a grain of rice. Samples from each brain can be depleted quickly, though, since the portions of use to researchers are often quite small.

The Harvard center’s most recent NIH contract, $12.7 million over five years, began in 2019, and it and the other repositories have been operating on temporary contract extensions since last year.

HHS did not respond to requests for comment. An emailed response cited the shutdown.

Each year, about 200 brains are donated to the Harvard center; about 60 to 70 percent come from outside New England, Berretta said.

Families that donate take comfort knowing their relatives are helping scientists understand some of the most intractable illnesses facing humanity.

Carol Vallone, chair of McLean Hospital’s board of trustees, encouraged her family to donate her father’s brain in 2020.

“He’ll be in hundreds of studies,” she said. “It’s a really nice way to keep him close and feel like he’s alive to us.”

Once the brain of the person with Huntington’s arrived at their lab, Nyanchoka and another tissue coordinator, Connie Chapman, donned protective gear, including gloves, masks, and plastic face shields, to guard against infectious material.

While conducting the dissection, Nyanchoka tried not to contemplate that the brain in her hands, typically weighing a little less than 3 pounds and smaller than a football, contained a lifetime of experiences and sensations felt by a person who had been alive just a few hours earlier.

“It’s a lot of responsibility,” she said. “We’re very thankful that this is something that they decided, honestly, to grace us with.”

The two exchanged terse updates while taking blood and spinal fluid samples, cutting away distinct parts of the brain such as the cerebellum and olfactory bulbs, and doing the slow, laborious work of peeling away protective membranes.

“Walking with tissue,” Chapman announced as she carried samples to be flash frozen in a bucket belching wisps of vapor from the dry ice.

Nyanchoka used a foot-long knife to halve the brain. Chapman put one hemisphere on ice for pathology and toxicology before also being used for research. The other was already softening, becoming harder to handle.

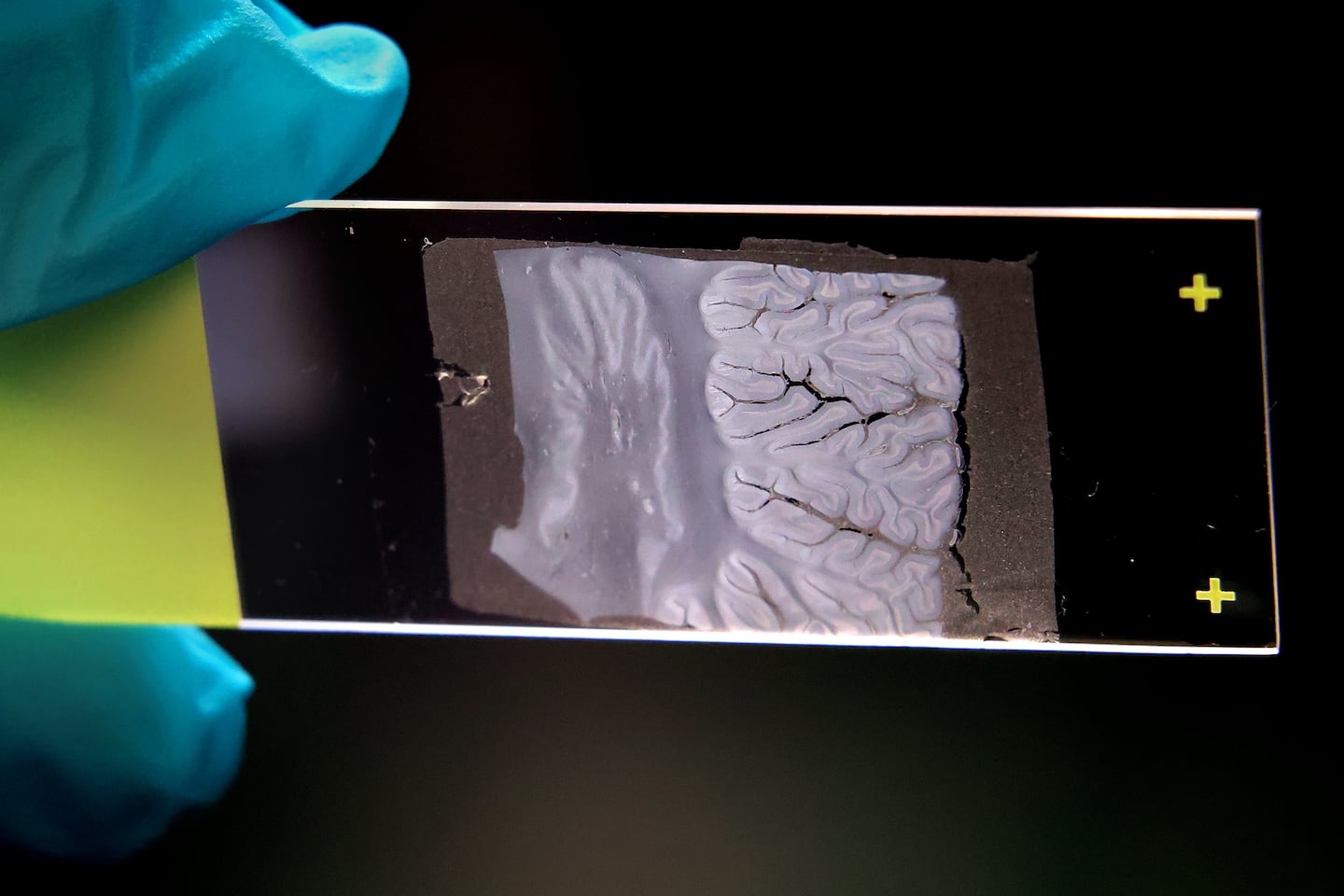

Nyanchoka dipped it in a chemical bath that hardened the tissue, then lowered on top of it a cage-like metal frame with slats every 5 millimeters. Those slats ensure her cuts across the brain, carving it into thin slices, are evenly spaced. Each brain yields between 30 and 35 cross sections that over decades will have pieces of them removed and shipped to research labs.

In a meeting before the dissection, the lab workers looked alarmed as Berretta discussed the budget.

“You’re not in danger of losing your jobs,” she quickly assured them.

There is a risk, though, that the center could not pay overtime for workers on call to receive a brain.

Unlike other organ donations, brain donations usually have to be approved by family after a person’s death. The brain banks need their cooperation for the most current health information about the donor and details of that person’s life. Families whose relatives suffered from a neurological or psychiatric condition are more likely to be aware donations are possible, Berretta said, but it’s a constant challenge to obtain healthy brains to serve as critical controls researchers use to identify key differences in ones affected by illness.

Berretta acknowledged how difficult a decision it is to decide to donate a brain, and is protective of those who participate. Without them, research wouldn’t be possible, she said. Along with the current threats to science, Berretta is as pained by the possibility of having to turn away donations because of budget cuts.

“If we’re not able to accept as many brain donations,” she said, “that’s going to be very difficult on the people who want to donate to us.”

Jason Laughlin can be reached at [email protected]. Follow him @jasmlaughlin.

First Appeared on

Source link