Black Death’s Global Spread Linked to a Volcanic Eruption on the Other Side of the Earth

The Black Death remains one of the most tragic and far-reaching pandemics in history, killing millions in Europe during the 14th century. New research published in Communications Earth & Environment reveals a fascinating connection between the plague’s devastating spread and a volcanic eruption. This groundbreaking study suggests that volcanic activity may have triggered a series of environmental and economic disruptions that made the spread of the plague almost inevitable.

The Unseen Forces Behind the Plague’s Spread

Historically, the origins and rapid spread of the Black Death have been shrouded in mystery. While it’s well-known that the disease was caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, what’s less understood is how the plague reached Europe and became so deadly. The recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment , led by historians and paleontologists, takes a novel approach to this question by suggesting that a volcanic eruption around 1345 CE may have played a pivotal role.

The researchers argue that volcanic activity, which likely occurred in the tropics, caused severe climatic disruptions. Using a combination of ice core data, tree rings, and historical records, they found evidence of unusually cold and wet summers between 1345 and 1347 across southern Europe. The spike in sulfur levels found in the ice cores from Antarctica and Greenland suggests that a major eruption released vast amounts of sulfur into the atmosphere, leading to a short-term cooling of the planet. This cooling, in turn, severely disrupted agricultural systems across Europe.

As crops failed and food shortages became widespread, famine ensued. This created a perfect storm for the plague, which had already been spreading in Central Asia. The researchers explain, “We used climate proxy and written documentary archives to argue that a yet unidentified volcanic eruption, or a cluster of eruptions around 1345 CE, contributed to cold and wet climate conditions between 1345 and 1347 CE across much of southern Europe.”

The Role of Trade Routes in Plague Transmission

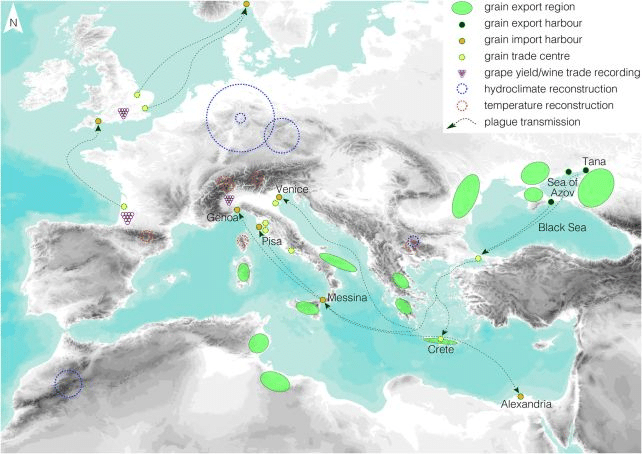

The study also highlights how the economic and trade routes of the time facilitated the spread of the disease. In 1347, the Italian maritime republics of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa were in dire need of grain to feed their populations. As a result of the famine caused by the cooling climate, these city-states were forced to reconfigure their supply chains. They turned to the Mongol empire, particularly the Golden Horde, for grain shipments from the Sea of Azov.

This shift in trade networks, however, unwittingly introduced a new risk. The grain shipments carried fleas infected with Yersinia pestis, which were thriving in the fur of rats aboard the ships. These fleas spread the disease to humans, particularly in port cities like Messina, Genoa, and Venice, where the first European outbreaks of the plague were recorded.

The study asserts, “This climatic anomaly and subsequent transregional famine forced the Italian maritime republics of Venice, Genoa, and Pisa to reconfigure their supply network and import grain from the Mongols of the Golden Horde around the Sea of Azov in 1347 CE.”

A Perfect Storm: Climate, Trade, and the Plague’s Arrival

The chain of events triggered by the volcanic eruption created an environmental crisis that fed directly into the social and economic vulnerabilities of 14th-century Europe. While the grain shipments from the Golden Horde were necessary for survival, they inadvertently became vectors for one of history’s deadliest pandemics. By the time the grain reached European ports, it was too late to prevent the disease from spreading.

The researchers explain that the dramatic changes in trade routes, along with the weakened state of European populations due to famine, contributed significantly to the rapid spread of the plague. The disease moved through the Mediterranean basin, reaching Italy in 1347 and continuing northward into France, Spain, and beyond. “The unusual change in long-distance maritime grain trade prevented large parts of Italy from starvation and distributed the plague bacterium Yersinia pestis via infected fleas in grain cargo across much of the Mediterranean basin, from where the second plague pandemic emerged into the largest mortality crisis in pre-modern times.”

The Aftermath: A Pandemic That Shaped History

The Black Death’s impact was not only medical but also social, economic, and cultural. The death toll was staggering, with estimates suggesting that anywhere from one-third to half of Europe’s population perished. Entire communities were wiped out, and the economic structure of Europe was forever changed. The epidemic also had profound effects on the course of human history, influencing everything from labor markets to social structures.

In hindsight, the confluence of volcanic eruption, climate change, famine, and the reconfiguration of trade routes seems like an improbable series of events. Yet, this study shows how environmental factors beyond human control, combined with economic needs, set the stage for one of history’s most catastrophic pandemics.

First Appeared on

Source link