Buried for 3.4 Million Years, New Fossil Evidence Is Removing Lucy From the Story of Human Evolution

A fossilized foot found in the dusty sediments of northern Ethiopia has reopened one of paleoanthropology’s most consequential questions: how many species of early hominins walked the Earth at the same time, and what paths did they take?

Initially recovered in the early 2010s, the foot was long suspected to hold evolutionary significance. Only recently, however, have new fossil associations and advanced analyses allowed scientists to make a more definitive classification. The result is a reinterpretation of a lesser-known hominin species that may have shared its landscape with Australopithecus afarensis, the species to which Lucy belongs.

Though diminutive in size, the fossilized bones hold implications far beyond their physical dimensions. They suggest that more than one hominin species experimented with bipedalism during the mid-Pliocene period, each adapting to distinct ecological challenges.

Published in Nature in early 2026, the findings draw from more than a decade of fieldwork in the Woranso-Mille region and integrate anatomical, geological, and isotopic data.

Fossil Foot Assigned to Australopithecus deyiremeda, Not Lucy’s Species

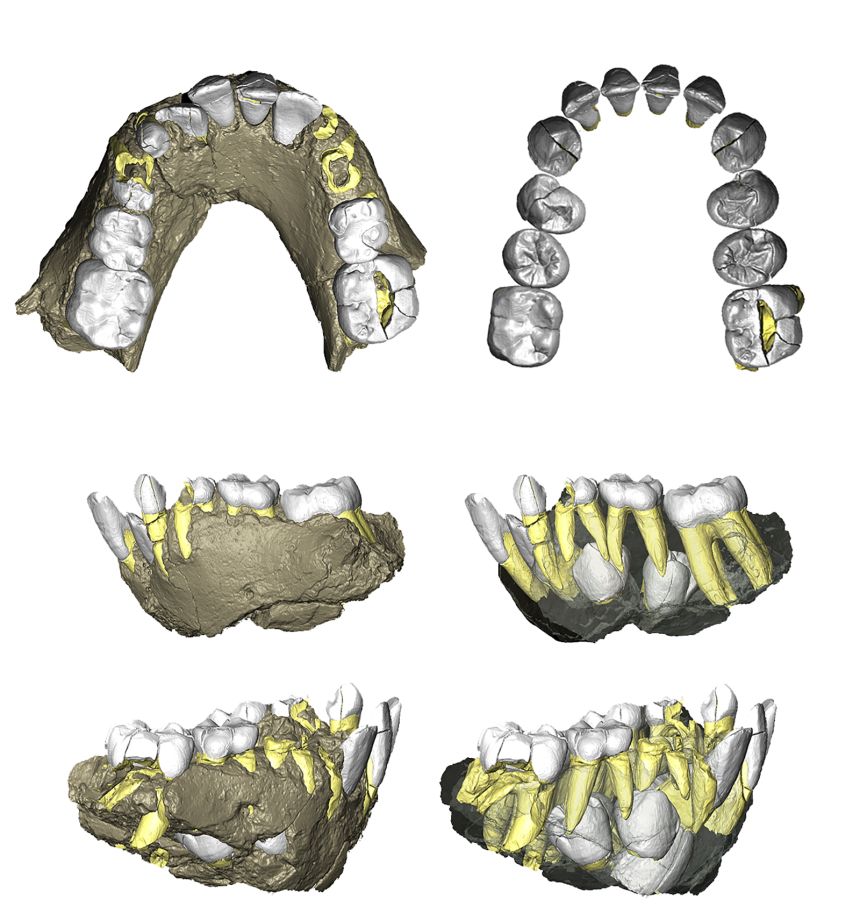

Researchers have now attributed the fossil foot, known as BRT-VP-2/73, to Australopithecus deyiremeda, a species first described in 2015 based on partial jaws and teeth found in the same Ethiopian region. The foot displays a mix of locomotor traits: a grasping big toe suited to climbing and other features consistent with upright walking.

The fossil’s age, determined through radiometric dating and stratigraphic context, ranges between 3.47 and 3.33 million years. This time frame overlaps directly with the presence of A. afarensis in nearby sites such as Hadar and Dikika, located just 4 to 5 kilometers away.

Despite the proximity, the Burtele hominin exhibits key differences in both dental and foot morphology. Newly recovered mandibles and teeth from the same stratigraphic horizon confirm that the Burtele specimen and the A. deyiremeda material share unique anatomical characteristics: smaller molars, simplified canine structure, and the absence of a lateral corpus hollow in the jaw. These features distinguish the species from A. afarensis.

The classification builds on earlier work establishing A. deyiremeda as a distinct mid-Pliocene species, based on fossils published in a 2015 Nature study that described cranial material found in the same region. Subsequent discoveries, including the Burtele foot, support the view that the species walked upright while retaining traits adapted for tree climbing.

The partial foot also includes a first metatarsal that lacks the dorsal articular isthmus found in Ardipithecus ramidus, another early hominin with climbing adaptations. Instead, its structure shares traits with later species such as Australopithecus africanus, particularly in the alignment and doming of the metatarsal head.

Dietary Evidence Reveals Niche Separation Among Coexisting Hominins

To assess the ecological role of A. deyiremeda, researchers sampled stable carbon isotopes from eight fossil teeth recovered from the Burtele site. The resulting δ13C values, averaging –10.2‰, indicate a diet dominated by C3 vegetation—primarily leaves, fruits, and other forest-based resources.

This dietary signature differs from that of A. afarensis, which exhibited a broader isotopic range and greater reliance on C4 plants from open grasslands. The divergence in food sources points to niche differentiation, allowing both species to inhabit the same region without direct competition.

Dental morphology supports this interpretation. Compared to A. afarensis, A. deyiremeda had a more primitive occlusal pattern, including molars with narrower crowns and premolars shaped for grinding tougher, fibrous vegetation. These adaptations suggest A. deyiremeda exploited different food resources, reinforcing the idea of ecological partitioning.

The concept of coexisting hominins in the Pliocene is further supported by additional studies of the Burtele foot, which described its unusual combination of climbing and walking traits. Researchers emphasized that this locomotor pattern differs substantially from that of Lucy, indicating that early hominin mobility strategies were more varied than previously believed.

Implications for Human Evolutionary Models and Ongoing Research

The co-occurrence of A. deyiremeda and A. afarensis within the same geographic and temporal window presents a significant shift in understanding mid-Pliocene hominin diversity. Rather than representing a single dominant lineage, the fossil record now supports a branching model, where multiple species explored different anatomical and ecological strategies.

The presence of overlapping species also raises questions about the linearity of human evolution. The mosaic traits observed in A. deyiremeda—primitive in some respects, derived in others—challenge the idea that obligate bipedalism, large molars, and other defining features evolved together.

Some researchers have begun questioning the central role of Lucy as a direct ancestor, arguing instead that A. afarensis may have been one of several side branches. As discussed in a 2025 analysis, the discovery of contemporaneous species with overlapping habitats and differing adaptations suggests a more complex evolutionary scenario.

Further excavation and isotope studies at sites like Burtele and Woranso-Mille, cataloged on educational platforms like Becoming Human, are expected to refine these phylogenetic relationships. Expanding the fossil sample will be critical for tracing the biomechanical evolution of bipedalism and clarifying how hominins adapted to diverse environmental pressures.

First Appeared on

Source link