Buried for 68 Million Years, Scientists Just Found a Dinosaur Egg Inside Another Egg

A fossil unearthed from central India has captured the attention of vertebrate paleontologists worldwide. Described by researchers as a dinosaur egg-within-an-egg, the specimen displays an internal structure never before documented in non-avian dinosaurs. The discovery, announced by scientists at the University of Delhi, signals a potential re-evaluation of assumptions about how some dinosaurs may have reproduced.

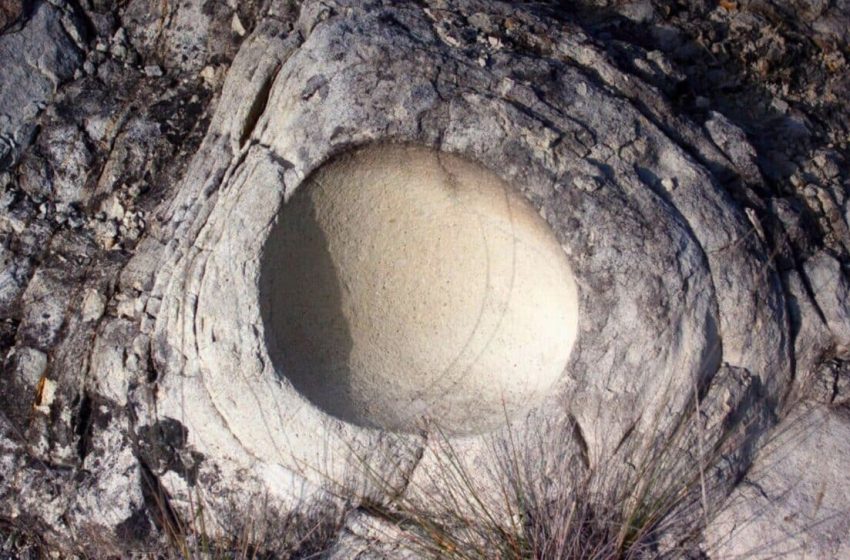

The find emerged from the Upper Cretaceous Lameta Formation in Madhya Pradesh, an area already known for extensive fossilized dinosaur nests. Researchers identified the anomaly within a titanosaur nest containing a clutch of eggs. One specimen, designated egg C, preserved two calcified shells: a complete inner egg, enclosed by an outer shell, with a physical separation between the two.

This internal architecture strongly resembles a condition known in birds as ovum-in-ovo, a reproductive anomaly that results in one egg forming around another. Before this discovery, such a phenomenon had only been documented in modern avian species. No confirmed instance had ever been attributed to a dinosaur, reptile, or other extinct amniote.

Evidence Confirms Egg-in-Egg Structure

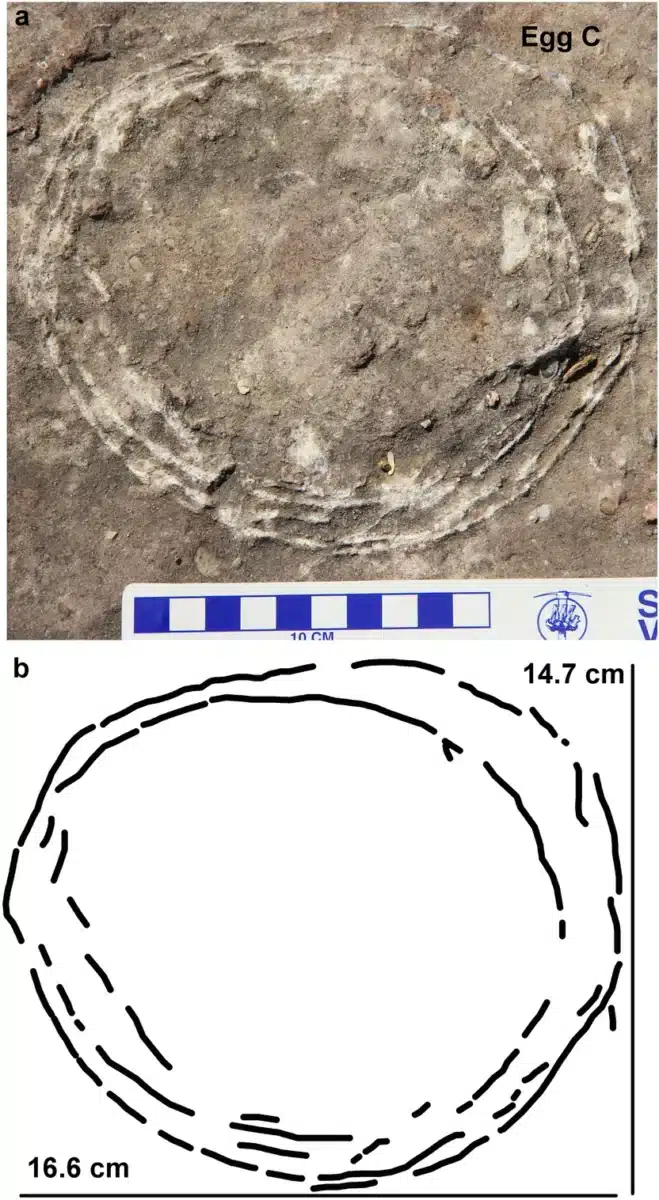

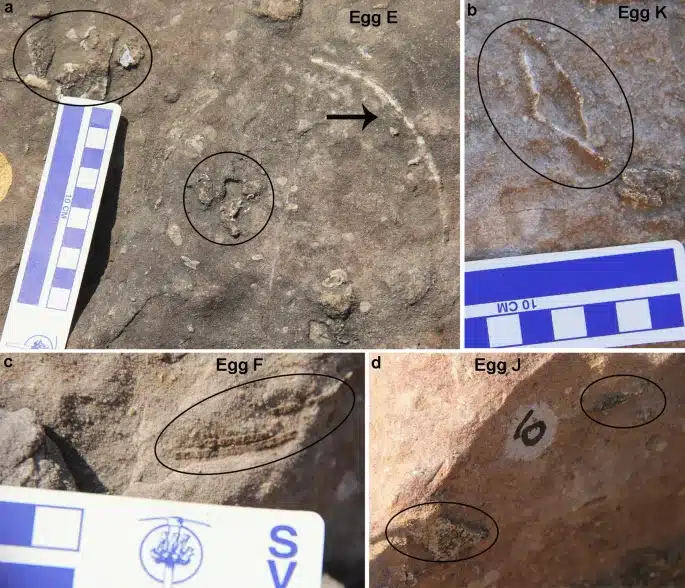

The fossil was recovered from nest P7, one of more than 50 titanosaur nesting sites identified during a multi-year survey of the Lameta exposures near Padlya village. Within this nest, egg C was found to contain two clearly defined and partially broken, circular eggshell outlines, with curved fragments lodged between them. These features were detailed in the peer-reviewed study published in Scientific Reports, part of the Nature portfolio.

Measurements taken in situ reported the specimen at 16.6 cm long and 14.7 cm wide. The outer and inner shell layers showed distinct separation, consistent in morphology with known ovum-in-ovo eggs from living birds. The authors documented the internal gap and curvature, supported by thin section microscopy and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis.

Published figures from the study show fan-shaped shell units and growth lines typical of the oospecies Fusioolithus baghensis, commonly attributed to titanosaurid sauropods. This parataxonomic identification aligns with previous reports on dinosaur eggshell microstructures from India, including surveys referenced in research summaries compiled by Guntupalli Prasad, who led the investigation.

The study explicitly ruled out taphonomic distortion. The symmetrical positioning of the internal shell, the curvature of the fragments, and the presence of a crescent-shaped gap along the upper shell supported a structured biological origin. Unlike multi-shelled eggs, where additional shell layers form in close contact, this fossil preserved a distinct spatial division between the two shells.

Reproductive Machinery of Dinosaurs More Complex than Thought

In living vertebrates, egg abnormalities such as multi-shelled structures, soft-shelled eggs, and deformities are relatively common in reptiles and birds. However, ovum-in-ovo pathology—in which a completed egg is pushed backward into the reproductive tract and encased in a second shell—is only verified in birds. It requires a specialized, segmented oviduct to form, a feature absent in most reptiles.

Birds exhibit sequential ovulation and have anatomically divided reproductive tracts, with distinct regions for membrane, albumen, and shell deposition. This internal specialization allows the type of muscular reversal necessary to form an egg within another. In contrast, most reptiles, including turtles and lizards, produce clutches through simultaneous ovulation in a generalized uterus.

Crocodilians, close archosaur relatives, present a more complex picture. Though they retain a generalized reptilian egg-laying strategy, they possess a segmented uterus that parallels avian anatomy. This intermediate condition has prompted comparisons to dinosaur reproductive physiology, particularly among sauropods, which show crocodile-like nesting behaviors, such as sediment burial and clutch formation.

The Indian fossil introduces a biological feature that overlaps more directly with birds than with crocodiles. The egg-in-egg structure implies the presence of internal segmentation and a reproductive mechanism capable of delaying or redirecting a shelled egg within the oviduct. No other fossil to date has provided this level of anatomical insight into sauropod egg physiology.

A Single Egg Challenges Decades of Paleontological Assumptions

The reproductive biology of titanosaurid dinosaurs, among the largest land animals in Earth’s history, remains poorly understood. This fossil represents a rare case where soft tissue physiology can be indirectly inferred from mineralized remains. If egg-in-egg formation occurred through the same processes seen in birds, it would require internal features—such as regionalized shell glands—that have not been associated with sauropods until now.

Field data from the Lameta Formation, where the fossil was found, continues to shape understanding of Late Cretaceous ecosystems in the Indian subcontinent. The formation is among the most significant dinosaur-bearing sequences in Asia and has yielded more than 100 titanosaur nests, along with multiple oospecies and isolated eggshells.

By identifying ovum-in-ovo pathology in one of these nests, the new study challenges earlier assumptions that sauropods lacked the anatomical complexity required for sequential ovulation. Although the fossil likely represents a rare anomaly, rather than a common reproductive feature, it introduces a new basis for anatomical comparison among archosaurs.

Fieldwork in the region is ongoing, with planned excavations set to resume by the end of 2026. Institutional stewardship remains with the University of Delhi, where the fossil and related eggshell specimens are stored and catalogued. No additional egg-in-egg structures have been identified to date, but researchers expect that increasing awareness of this pathology may lead to renewed examination of previously collected specimens.

The Padlya specimen remains the only confirmed example of ovum-in-ovo pathology in a dinosaur, preserved with sufficient clarity to establish both its biological origin and evolutionary significance.

First Appeared on

Source link