Dinosaur Eggs as Large as Cannonballs Were Found Filled With Massive Crystals Instead of Ancient Bones

In a shallow basin in eastern China, two nearly spherical dinosaur eggs surfaced with an unexpected interior. The outer structure was intact, the contents anything but. Inside were no bones, no embryonic traces, but clusters of gleaming mineral crystals arranged in hollow chambers. Scientists had seen fossilised eggs before, but not like these.

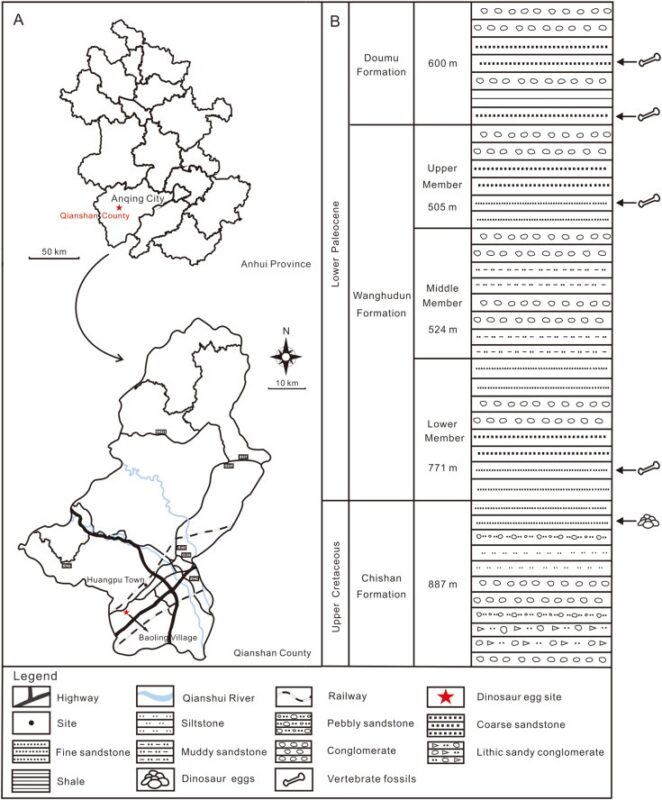

The eggs were discovered in Anhui Province, a region long known to preserve fragments of Late Cretaceous life. Recent fieldwork across parts of southern China has drawn renewed attention to fossil-rich layers, revealing well-preserved nests, delicate embryonic forms, and now, unusual crystalline structures where life once began. What these finds offer is not just a record of individual organisms, but windows into broader ecological patterns during a volatile chapter in Earth’s history.

Fossilised dinosaur eggs are not uncommon. Yet their preservation often varies, shaped by complex interactions between biology and environment. In most cases, mineralisation follows decay. Occasionally, the process leaves behind a trace of the embryo. Rarely, it replaces it altogether. When it does, the result can raise new questions about how fossilisation works, and what it conceals.

Unusual mineralisation in fossilised eggs

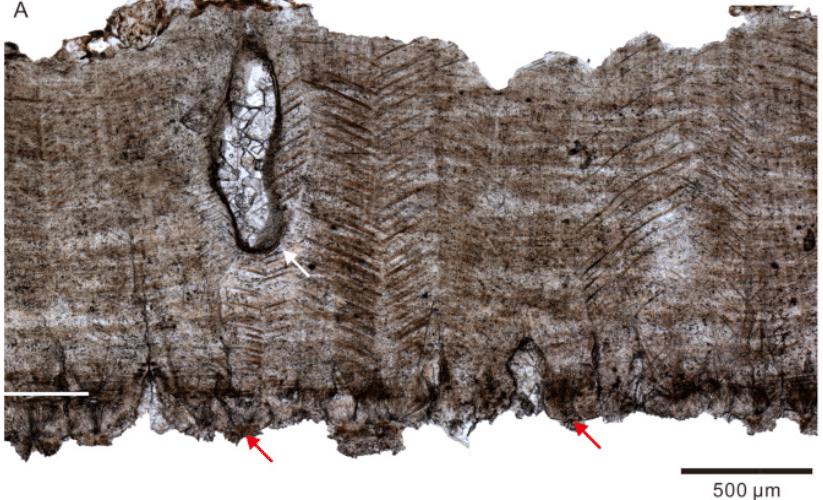

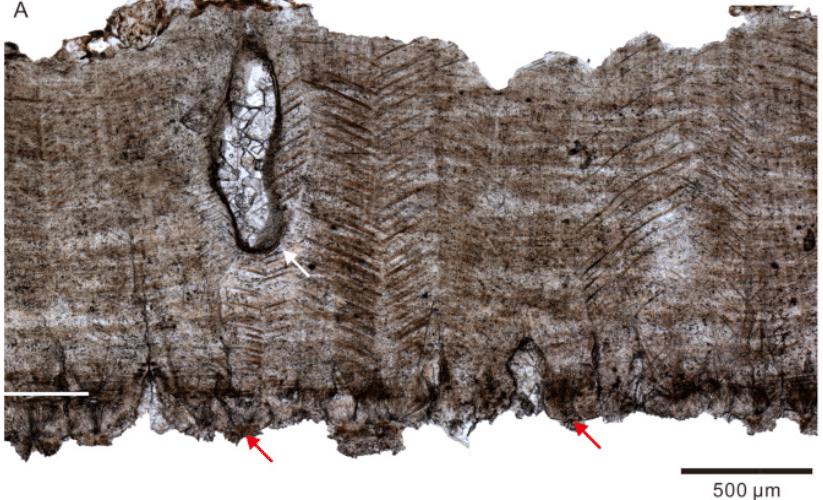

The crystal-filled eggs, measuring roughly 13 centimetres across, were analysed by a team led by Qing He of Anhui University and the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology (NIGPAS). Instead of preserving embryonic remains, each egg contained compact clusters of calcite, a form of calcium carbonate. The minerals had formed in hollow spaces, filling the interior where organic material had once been.

Described as a new oospecies, Shixingoolithus qianshanensis, the eggs were assigned to Stalicoolithidae, a group defined by thick shells and spherical forms. This classification is based on parataxonomy, which allows fossilised eggs to be categorised even in the absence of bones. Microscopic analysis of the shell structure supported this assignment, showing patterns consistent with other stalicoolithid specimens.

The researchers reported that groundwater rich in dissolved minerals likely infiltrated the buried eggs after the organic contents had decayed. Over millions of years, this process allowed calcite to crystallise inside the eggs, preserving their internal voids in geometric patterns. This form of replacement, while uncommon, illustrates how specific geological conditions can preserve fossils in atypical ways.

“New oospecies Shixingoolithus qianshanensis represents the first discovery of oogenus Shixingoolithus from the Qianshan Basin,” the authors noted in their published findings, reported by Earth.com.

Preserved embryos in southern China

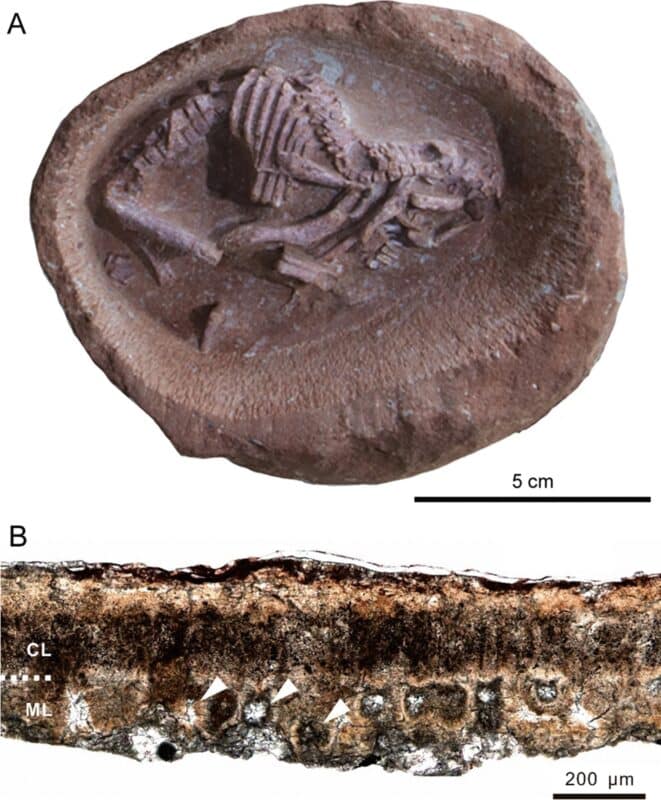

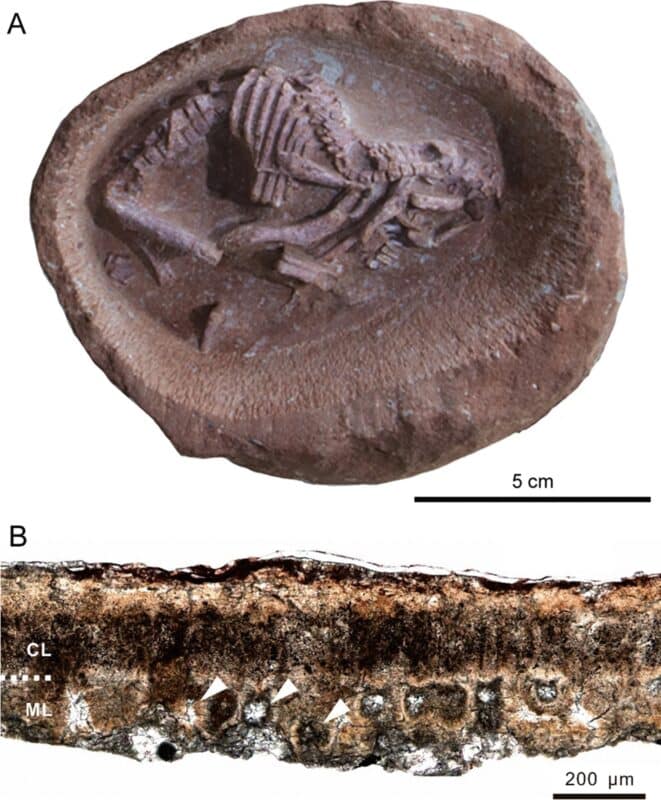

While the Qianshan eggs lacked embryonic material, a separate discovery in the Ganzhou Basin offered a contrasting view. There, a clutch of eggs attributed to the Spheroolithidae revealed well-preserved hadrosauroid embryos. Found during a construction project in Jiangxi Province, the fossils were analysed in a peer-reviewed study published in BMC Ecology and Evolution.

Two embryos, designated YLSNHM 01328 and 01373, showed distinct skeletal features including vertebrae, cranial bones, and developing limbs. The morphology of their bones resembled hadrosauroid species such as Tanius sinensis and Levnesovia transoxiana, though the exact taxonomic identity remains uncertain due to developmental stage and incomplete preservation.

The eggs were relatively small, with an estimated volume of 660 millilitres, and the embryos were in early growth phases. These characteristics suggest a less derived form of hadrosauroid, distinct from the larger, more developed embryos found in lambeosaurine eggs. The researchers noted that traits associated with large egg size and advanced hatchlings likely evolved later within the group.

The study concluded that these embryos provide insight into ontogeny within non-lambeosaurine hadrosauroids. Structural differences in the eggshell and skeletal development point to evolutionary divergence in reproductive strategies within the broader Hadrosauroidea clade.

Geological context and preservation conditions

Both Qianshan and Ganzhou lie within regions marked by complex geological activity during the Late Cretaceous. Volcanic ash, episodic flooding, and fluctuating climate cycles contributed to rapid burial and mineral preservation. These conditions created environments where fossils, including delicate eggs and embryos, could be sealed from oxygen and decay.

The Hekou Formation, where the Jiangxi embryos were found, consists of layered conglomerates, sandstones, and mudstones deposited in an alluvial fan system. The presence of carbonate nodules, caliche horizons, and desiccation cracks suggests a semi-arid to subhumid climate with periodic drying. These features align with preservation conditions known to protect organic structures from degradation.

Microscopic examination of the eggshells revealed two-layered structures common in dinosaur eggs: a mammillary layer and a continuous outer layer. The crystals inside the Qianshan specimens likely formed after diagenesis, a process of chemical change in sediments over time. A related analysis in the Journal of Palaeogeography describes similar crystal formation in Late Cretaceous fossil eggs, supporting this interpretation.

By comparing eggs from multiple locations, researchers are better able to differentiate between taphonomic effects and original biological features.

Timeline and extinction context

The fossils from Jiangxi and Anhui are dated to the Maastrichtian stage, within the final few million years before the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event. This situates them close in time to the Chicxulub impact, when a 10-kilometre-wide asteroid struck the Yucatán Peninsula, producing a crater over 200 kilometres wide.

A detailed overview by NASA Science outlines how the impact released vast amounts of carbon dioxide, sulphur dioxide, and fine particulate matter into the atmosphere. These emissions caused abrupt climate disruption, halted photosynthesis, and led to widespread ecological collapse.

The Chicxulub crater, now buried beneath over a kilometre of sediment, remains the focus of scientific drilling projects aimed at understanding the energy of the impact and its global effects. Geophysical anomalies and core samples confirm that the structure matches the age and magnitude required to explain the mass extinction at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary.

While the fossil eggs themselves do not link directly to the extinction mechanism, their condition and stratigraphic position contribute to a more detailed understanding of ecosystems at the end of the Mesozoic. By analysing eggshell chemistry, embryonic development stages, and sedimentary context, scientists can trace patterns of reproductive behaviour and environmental change leading up to the mass extinction.

First Appeared on

Source link